views

- Begin plotting your story by writing down concepts you find interesting. These initial ideas can be detailed (two opposing samurai falling in love) or simple (a story about grief).

- A good plot requires a relatable protagonist that reacts to situations organically. The best way to create a dynamic character is to give them clear goals and flaws.

- Conflict adds tension to your plot. Place your characters in situations where they struggle and increase the difficulty as your story progresses.

Outlining, Structure, & Worldbuilding

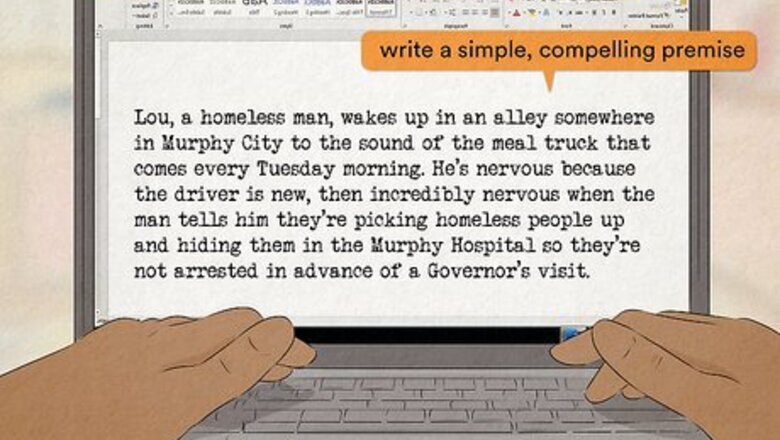

Start with a simple, compelling premise and build from there. Begin plotting your story by finding a concept you think is engaging. It can be big (dinosaurs destroying an island like in Jurassic Park) or small (men having a long talk about justice like in 12 Angry Men). Brainstorm your potential concepts by writing out ideas as they come to you. They can be in long sentences, loose words, or entire paragraphs. Just get them on the page; you’ll build and polish these concepts later. Consider getting a notepad. The act of writing by hand can get your ideas flowing more freely. You can find inspiration for concepts in books, music, paintings, or even people.

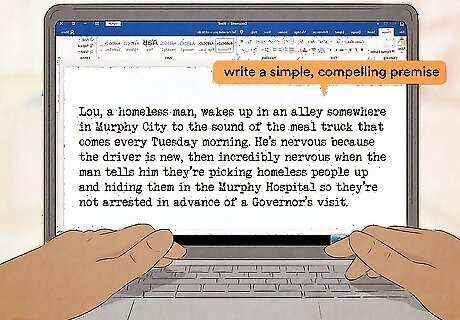

Choose an immersive setting. The world your story takes place in will also heavily impact your plot. Your setting can be based on a real locale or entirely fictional. What matters most is that you show, don't tell. Instead of merely describing locations, write specific, tactile visuals that place the reader directly into your world. For example, instead of simply saying that a barn is red, describe the place’s peeling paint, the rust that is forming, and the pink shade on the walls that were caused by the sunlight. Instead of saying a character is sad, show them holding back tears or maintaining a stoic expression while everyone around them is joyous.

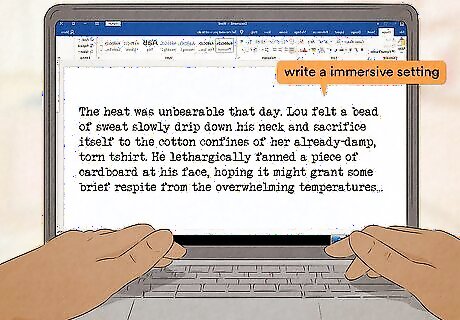

Use the 7 common plots for inspiration. Identify what type of story you want to write about. Play with genre conventions and decide if you want your narrative to be comedy, action, mystery, romance, adventure, nonfiction, or something else entirely! Almost every story falls into 1 of 7 common plot outlines. Consider which of the following might be the most effective way to tell your tale: Comedy: These stories are usually shorter and meant to showcase the absurdity or silliness of human nature. Characters are often more broad, and the resolutions are usually happy. (Examples: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Don Quixote) Tragedy: A character has a major flaw that ends up being their undoing. Endings are often sad, as a once happy protagonist falls from grace. (Examples: Macbeth, Oedipus Rex, Hamilton) Hero’s Journey: A protagonist goes on a quest to get somewhere or find a special object. They face obstacles and meet people that teach them along the way. (Examples: The Odyssey, The Lord of the Rings, Interstellar) Rags to Riches: A poor character acquires wealth, power, or status, loses it, then must fight to gain it back. These stories often explore the nature of power and responsibility. (Examples: Aladdin, Jane Eyre, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory) Rebirth: An event (either supernatural or realistic) forces a jaded or corrupt character to live a better, more generous life. These stories often have spiritual themes and draw from religious texts for inspiration. (Examples: Pride and Prejudice, Beauty and the Beast, Groundhog Day) Overcoming the monster: A battle of Good vs. Evil where a character must fight an opposing force that threatens the well-being of their family, home, or overall status quo. (Examples: Star Wars, Dracula, Perseus) Voyage and Return: A character visits a strange new world, adapts to it, and returns home with a new perspective on life. (Examples: The Wizard of Oz, Gulliver’s Travels, The Lion King)

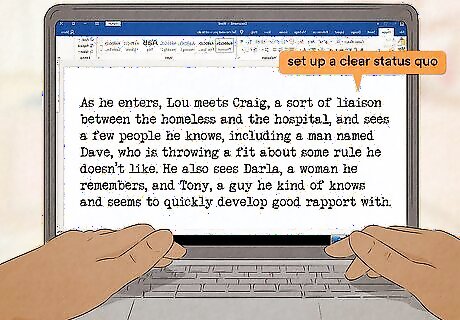

Set up a clear status quo at the beginning of your story. Once you’ve determined the overall concept and type of story you want to tell, begin setting up your exposition. The exposition covers all the necessary background information and a few key details about your hero. Introduce your main character (ideally within the first 10 pages) and create a clear picture of what their day-to-day looks like. There are several ways you can set up your character’s status quo (current situation), including: Dialogue: Have your characters talk about their lives in conversation. Narration: Let the audience hear what’s going on inside your character’s head and how they feel about the world around them. This usually works better in prose. Conflict: Have your character face an obstacle early on to show what they stand for. Objects and symbols: Focus on items (newspaper clippings, household furniture, clothes) that give a clear picture of the world your character lives in. Try to make your status quo contrast with the journey you plan on sending your character on. The further your characters venture out of their comfort zone, the more opportunity they have to grow.

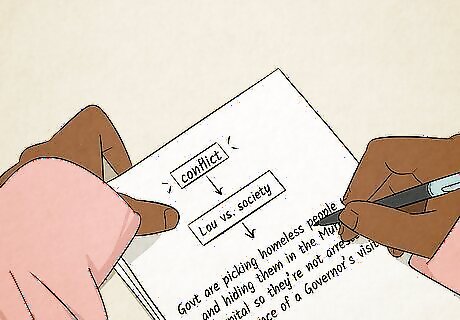

Brainstorm obstacles and opposing forces to create conflict. Figure out what you want the central antagonist to be. This can be another character, a group of characters, or even the protagonist themselves. You can have multiple opposing forces against your main character, but try to lock in on one clear enemy they have to overcome. Different obstacles create different types of stories. For example: Character vs. self has a character working through their own inner demons and flaws. These stories are often dramas, tragedies, and tales of rebirth. (Examples: Good Will Hunting, Emma, Hamlet) Character vs. character is the most common conflict; a protagonist must fight an antagonist who challenges their core values. These stories can be any genre but usually fall into the “Overcoming the Monster” plot. (Examples: Star Wars, Othello, Crime and Punishment) Character vs. society explores your protagonist challenging the social norms and bigotry of the people around them. These stories are often farcical comedies or have strong undercurrents of social commentary. (Examples: To Kill a Mockingbird, The Color Purple, Blazing Saddles) Character vs. supernatural has the character fighting against a force with special powers. These stories are always fiction, usually sci-fi or fantasy. (Examples: Harry Potter, The Odyssey, Ghostbusters) Character vs. technology has a protagonist fighting against a machine or technological advancement (usually one similar to a device that’s taking off in the real world, like AI). These stories are usually a form of science fiction, but they can be any genre. (Examples: Blade Runner, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Matrix) Character vs nature stories are often visual. The protagonist must fight against the natural world. These stories are very adventure-based. (Examples: Cast Away, Hatchet, The Martian)

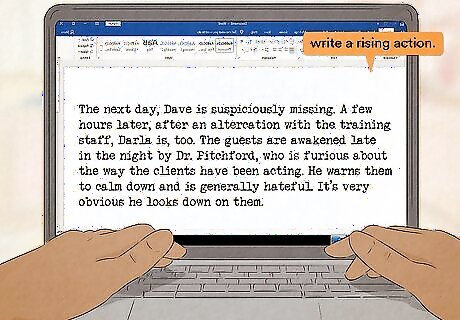

Create a rising action. The rising action is the sequence of events that ultimately leads to the climax (point of ultimate tension). To craft a powerful rising action, continue raising the stakes for your character with each obstacle they face. With each challenge, have your character learn something more about themselves, their potential, or their limitations. Pay attention to cause-and-effect in your rising action. Every action has a reaction, and no events are random. Each decision the character makes should affect future situations. The best structure to create a meaningful rising action is “[Character] did _____. Because of that, _____ happened so they _____.” Utilize your world to impact your rising action, too. For example, if your character lives on Mars 3000 years in the future, your character should probably deal with struggles unique to that planet, rather than common Earth problems.

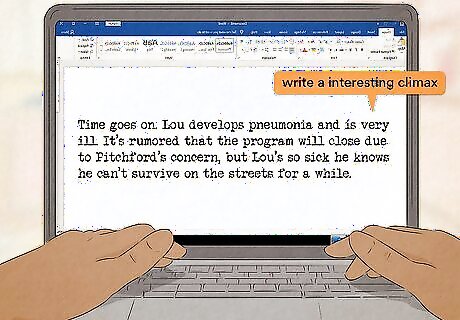

Come up with an interesting climax. The climax is the moment in which your characters will face their ultimate challenge. Normally it involves multiple characters and is a result of all the events culminating in your rising action. Write your climax near the end of the story and set up a moment in which the protagonist seems defeated. By facing this defeat, they’ll be able to learn more about themselves and their journey. In Oedipus Rex, the climax occurs when Oedipus realizes his hubris has made him fulfill the prophecy so he blinds himself as punishment for his actions. Because this story is a tragedy, the climax is dark, sad, and violent. In Shrek, the climax comes from the reveal that Fiona is an ogre too. Because the film is a subversive comedy about beauty standards, the silly plot twist matches the movie’s tone.

Write a falling action and resolution that feels appropriate for your story. The falling action is the opposite of a rising action. It occurs after the climax, slows the story down, and allows characters to apply the lessons they learned on their journey. Your resolution is a culmination of these lessons. It places the character in a new (often better territory), pays off the events of the climax and exposition, and usually clarifies the overall theme of your piece. In Little Red Riding Hood, the falling action covers the part where the Woodsman finds Little Red and saves her from the Big Bad Wolf. Because Little Red learns her lesson on gullibility in the climax (when she discovers Granny’s been eaten), her resolution is happy and simple. To create a more effective conclusion, set up story beats early on that you can pay off later. For example, at the beginning of Game of Thrones, Theon Grey Joyce betrays the Stark family. However, he ends the series fighting (and dying) to protect their name. EXPERT TIP Rain Kengly Rain Kengly wikiHow Technology Writer Rain Kengly is a wikiHow Technology Writer. As a storytelling enthusiast with a penchant for technology, they hope to create long-lasting connections with readers from all around the globe. Rain graduated from San Francisco State University with a BA in Cinema. Rain Kengly Rain Kengly wikiHow Technology Writer "If you find yourself struggling to plot a story from beginning to end, start with the ending and work backward! Knowing how and where you want your story to end can help you understand what developments your characters must have to get there."

Creating Unique Characters

Set up your story’s characters with clear goals and motivations. A good plot requires an interesting character to react organically. The more the audience feels like your character is behaving realistically, the more natural and engaging the story will be. The best way to create a dynamic character is to give them clear wants that suit their world and the tone of your story. Ask yourself the following questions to determine your character’s goals: Does your character like attention or avoid it? How big of a role does fear play in their day-to-day activities? Does your character think they’re intelligent or dumb? How would they define these words? Does your character prefer to leap into action or stay back and think? What are your characters’ regrets? If your plot is a fantasy epic, your characters may have lofty, larger-than-life ambitions like finding a magic amulet or gaining special powers. For a more subtle drama, their wishes may be smaller: love, getting into the right college, reuniting with family, etc.

Give your characters a unique point-of-view. Your reader/audience is more likely to be invested in the plot if they feel the characters offer a fresh and diverse perspective. Think about common tropes you often see for heroes, villains, love interests, comic relief, etc. Then, try to add new dimensions or layers to their personalities that challenge these expectations. For example, in Brooklyn Nine-Nine, we expect Captain Holt to be an aggressive, loud (possibly even bigoted) police chief. However, he’s gentle, and measured, and the prejudice he’s experienced as a Black and gay man makes him open-minded and empathetic. All of this makes him more compelling.

Draw inspiration from real-life people. The best way to avoid stereotypes and make a story feel grounded is to base its characters on people you’ve seen in the real world. Instead of looking for plot and character motivations in media, think of your family, friends, co-workers, or even strangers you meet in line at the grocery store. What are they afraid of? What do they want? What do they need? Use these realistic fears and goals to craft your characters’ personalities. For example, if you have an uncle who’s a hypochondriac and a friend who wants to be a stuntman, you could combine these to create a character who loves stunts but is afraid of the toll it takes on their body. Keep a journal to write down what people in your life say. In art and life, people’s dialogue often reflects who they are.

Make your characters flawed and relatable. Avoid making your characters perfect. Allow them to make mistakes and struggle. Audiences love underdogs, so the more opportunities you give your characters to fail or face adversity, the more they’ll empathize with their struggles. The more investment your audience has in a character, the more likely they are to follow them through the story.

Build multi-dimensional story arcs for your characters. As your character’s situations change on their journey, their worldview and goals should change too. The further you can push your character throughout the plot to make them change organically, the more rich and emotional their arc will be. Use the following strategies to help craft your arc: Set up a need, as well as a want. Ideally, your character will have a clear goal as well as a lesson they must learn to live a better life. It’s more realistic and satisfying if a character doesn’t necessarily get what they want, but, as the Rolling Stones sing, gets what they need. Create irreversible consequences. Every decision your character makes should set off a new chain of events. Results can be good or bad, but no choices happen in a vacuum; they should make an impact in some way. Let the character show their strengths and overcome weaknesses. Giving your characters skills that they can apply on their journey allows them to be more directly involved in the story. Create a dark night of the soul. At one point in the story, your character should feel like all is lost. This surrender offers them a new perspective that they can use to re-evaluate their goals.

Adding Conflict & Style

Put your characters in story situations that invite conflict and difficulty. Conflict is the struggle your characters must go through to create a satisfying plot. The harder you can make life for your main character throughout the story, the more engaged your audience will be. It can help to work backward. Think of your character’s worst nightmare. Then, slowly create a chain of events that sends them hurtling in that direction. For example, if your character hates confrontation, find story beats that force them to debate and get into fights as often as possible. If your character is a control freak, strip them of power and force them to ask for help. Don’t be afraid to be mean to your characters! Relentlessness makes good storytelling.

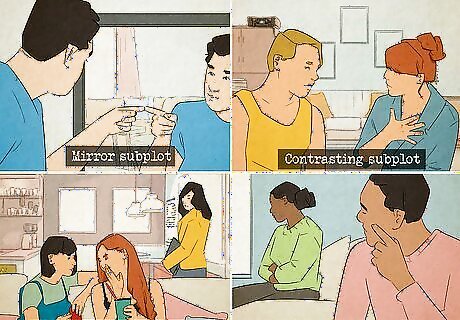

Deepen your main plot with subplots. A subplot is a minor plot that runs within (and often parallels) the main story. Use subplots to add new layers of depth to your central narrative and offer more insight into your supporting characters. The 4 main types of subplots include: Mirror subplot: A smaller-scale conflict that mirrors the main conflict which helps teach the character how to resolve the core issue. Contrasting subplot: A secondary character facing similar circumstances and dilemmas as the main character, but making different decisions that have a polar opposite (and often less effective) outcome. Complicating subplot: A secondary character making things worse for the main character. These subplots often appear right around the middle of the story to raise the stakes once the character feels comfortable. Romantic subplot: A relationship that often complicates or adds risk to the main plot.

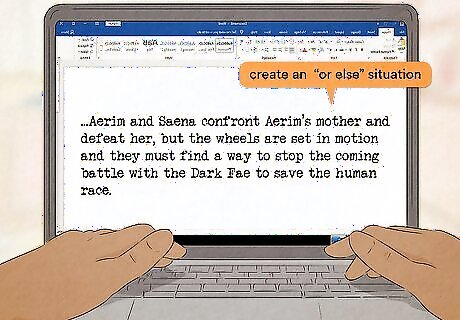

Add an “or else” to give your narrative stakes. Set up a worst-case scenario that will happen if your main character fails. They must face their weaknesses, continue with their journey, or give up what they want “or else” everything will fall apart. For example, in Die Hard, John McClane must overcome his fear of heights and save his relationship, or else the terrorists will succeed and harm innocent people. Your “or else” doesn’t always have to be life or death. The stakes just have to feel heavy for your character. For example, in Up, if Carl doesn’t fly his house away, he’ll be fine physically (and go to a nice retirement home). However, he’ll feel like he disappointed Ellie, his late wife. Adding a ticking clock is a great way to make your “or else” more clear and specific. Give a set time frame that your character has to complete their goal, and clarify what will happen if they fail to meet this deadline.

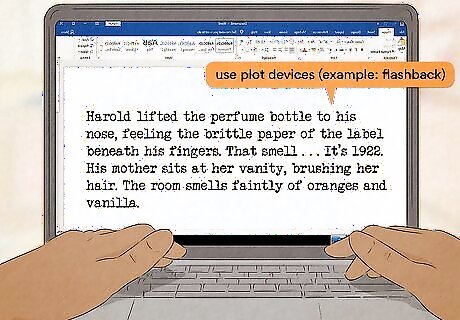

Use plot devices to increase tension and build momentum. Every genre has a set of techniques they use to move their plot forward. Try implementing a few of these artifices into your plot to inject more energy into your story. A few of the most popular plot devices are: Chekov's Gun: An object appearing to be insignificant later resolves the conflict. Flashback: A recount of events that happened before the current story, which fills in crucial backstory. MacGuffin: An object or goal that the protagonist is motivated to pursue which makes their life more difficult. Red Herring: An object or character that’s used to draw the audience’s attention away from something crucial within the plot. Deux Ex Machina: A resolution that appears to come out of the blue. Dramatic Irony: A situation where the audience knows something the character doesn’t (that often leads to the character’s downfall).

Consider pacing and only write what’s absolutely necessary. As you write, re-read to ensure that every detail you include serves a purpose for the overall plot. Do they enhance the narrative, deepen the characters, or convey the mood/tone? If not, cut them! In addition, pace your story so it gets more compelling as it goes along. Don’t overload your story’s beginning with tension; distribute action and conflict equally throughout the piece. The more your narrative builds, the more invested your audience will be!

Comments

0 comment