views

Understanding the Properties of Gases

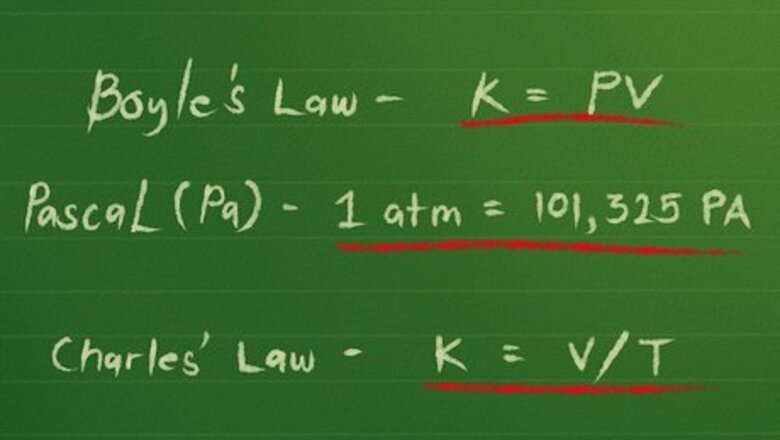

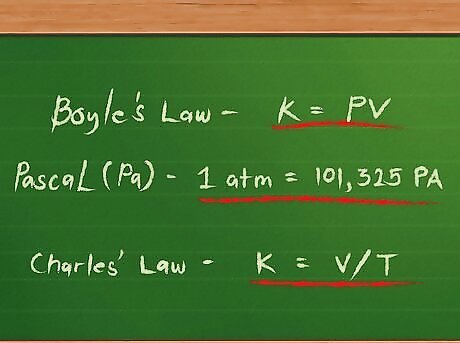

Treat each gas as an “ideal” gas. An ideal gas, in chemistry, is one that interacts with other gases without being attracted to their molecules. Individual molecules may strike one another and bounce off like billiard balls without being deformed in any way. The pressures of ideal gases increase as they are squeezed into smaller spaces and decrease as they expand into larger areas. This relationship is called Boyle’s Law, after Robert Boyle. It is written mathematically as k = P x V or, more simply, k = PV, where k represents the constant relationship, P represents pressure and V represents volume. Pressures may be given using one of several possible units. One is the pascal (Pa), defined as a force of one newton applied over a square meter. Another is the atmosphere (atm), defined as the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere at sea level. A pressure of 1 atm is equal to 101,325 Pa. The temperatures of ideal gases increase as their volumes increase and decrease as their volumes decrease. This relationship is called Charle’s Law after Jacques Charles. It is written mathematically as k = V / T, where k represents the constant relationship between the volume and temperature, V again represents the volume, and T represents temperature. Temperatures for gases in this equation are given in degrees Kelvin, which are found by adding 273 to the number of degrees Celsius in the gas’ temperature. These two relationships can be combined into a single equation: k = PV / T, which can also be written as PV = kT.

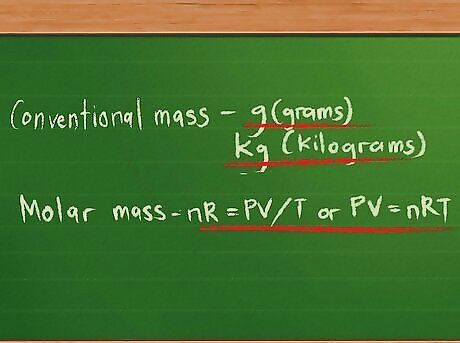

Define the quantities the gases are measured in. Gases have both mass and volume. Volume is usually measured in liters (l), but there are two kinds of mass. Conventional mass is measured in grams or, if there is a sufficiently large mass, kilograms. Because of how lightweight gases usually are, they are also measured with another form of mass called molecular mass or molar mass. Molar mass is defined as the sum of the atomic weights of each atom in the compound the gas is composed of, with each atom compared against the standard value of 12 for carbon’s molar mass. Because atoms and molecules are too small to work with, quantities of gases are defined in moles. The number of moles present in a given gas can be found by dividing the mass by the molar mass and can be represented by the letter n. We can replace the arbitrary k constant in the gas equation with the product of n, the number of moles (mol), and a new constant R. The equation can now be written nR = PV/T or PV = nRT. The value of R depends on the units used to measure the gases’ pressures, volumes, and temperatures. For volume in liters, temperature in degrees Kelvin, and pressure in atmospheres, its value is 0.0821 L atm/K mol. This may also be written 0.0821 L atm K mol to avoid using the division slash with units of measure.

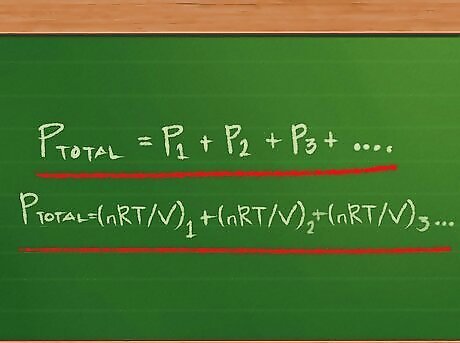

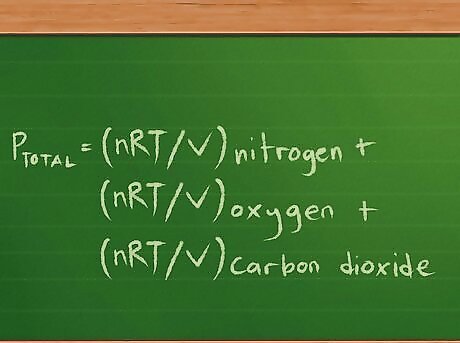

Understand Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures. Developed by chemist and physicist John Dalton, who first advanced the concept of chemical elements being made up of atoms, Dalton’s Law states that the total pressure of a gas mixture is the sum of the pressures of each of the gases in the mixture. Dalton’s Law can be written in equation form as Ptotal = P1 + P2 + P3 … with as many addends after the equal sign as there are gases in the mixture. The Dalton’s Law equation can be expanded on when working with gases whose individual partial pressures are unknown, but for which we do know their volumes and temperatures. A gas’ partial pressure is the same pressure as if the same quantity of that gas were the only gas in the container. For each of the partial pressures, we can rewrite the ideal gas equation so that instead of the form PV = nRT, we can have only P on the left side of the equal sign. To do this, we divide both sides by V: PV/V = nRT/V. The two V’s on the left side cancel out, leaving P = nRT/V. We can then substitute for each subscripted P on the right side of the partial pressures equation: Ptotal =(nRT/V) 1 + (nRT/V) 2 + (nRT/V) 3 …

Calculating Partial, Then Total Pressures

Define the partial pressure equation for the gases you’re working with. For the purposes of this calculation, we’ll assume a 2-liter flask holds 3 gases: nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), and carbon dioxide (CO2). There are 10g of each gas, and the temperature of each gas in the flask is 37 degrees C (98.6 degrees F). We need to find the partial pressure for each gas, and the total pressure the gas mixture exerts in the container. Our partial pressure equation becomes Ptotal = Pnitrogen + Poxygen + Pcarbon dioxide. Since we’re trying to find the pressure each gas exerts, we know the volume and temperature, and we can find how many moles of each gas is present based on the mass, we can rewrite this equation as : Ptotal =(nRT/V) nitrogen + (nRT/V) oxygen + (nRT/V) carbon dioxide

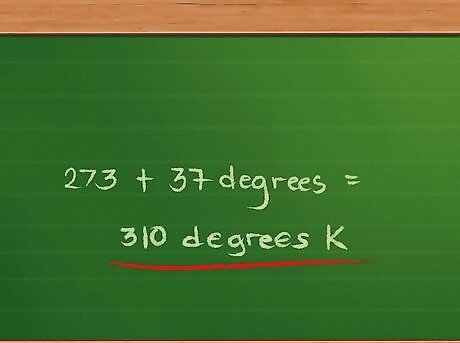

Convert the temperature to degrees Kelvin. The Celsius temperature is 37 degrees, so we add 273 to 37 to get 310 degrees K.

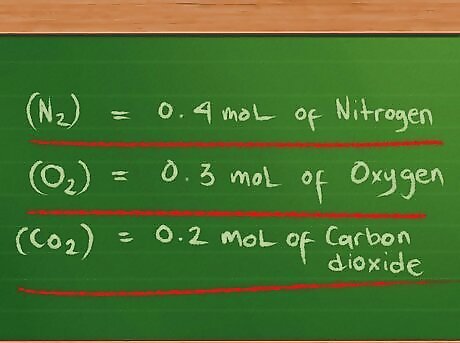

Find the number of moles of each gas present in the sample. The number of moles of a gas is the mass of that gas divided by its molar mass, which we said was the sum of the atomic weights of each atom in the compound. For our first gas, nitrogen (N2), each atom has an atomic weight of 14. Because the nitrogen is diatomic (forms two-atom molecules), we have to multiply 14 by 2 to find that the nitrogen in our sample has a molar mass of 28. We then divide the mass in grams, 10 g, by 28, to get the number of moles, which we’ll approximate as 0.4 mol of nitrogen when rounding to the nearest tenth. For our second gas, oxygen (O2), each atom has an atomic weight of 16. Oxygen is also diatomic, so we multiply 16 by 2 to find the oxygen in our sample has a molar mass of 32. Dividing 10 g by 32 gives us approximately 0.3 mol of oxygen in our sample. Our third gas, carbon dioxide (CO2), has 3 atoms: one of carbon, with an atomic weight of 12; and two of oxygen, each with an atomic weight of 16. We add the three weights: 12 + 16 + 16 = 44 as the molar mass. Dividing 10 g by 44 gives us approximately 0.2 mol of carbon dioxide.

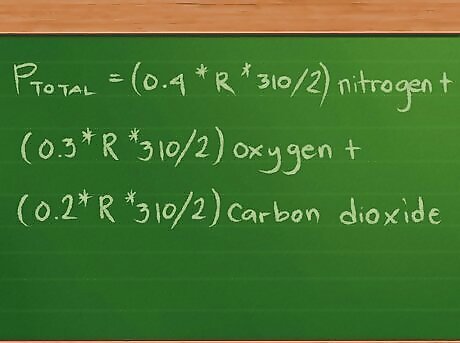

Plug in the values for the moles, volume, and temperature. Our equation now looks like this: Ptotal =(0.4 * R * 310/2) nitrogen + (0.3 *R * 310/2) oxygen + (0.2 * R *310/2) carbon dioxide. For simplicity’s sake, we’ve left out the units of measure accompanying the values. These units will cancel out after we do the math, leaving only the unit of measure we’re using to report the pressures in.

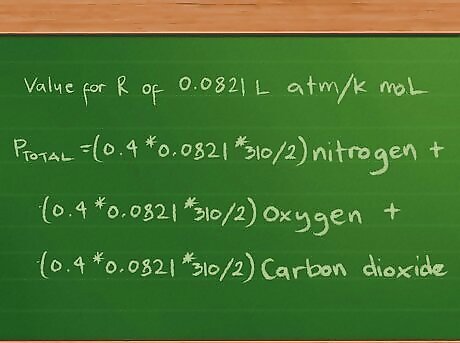

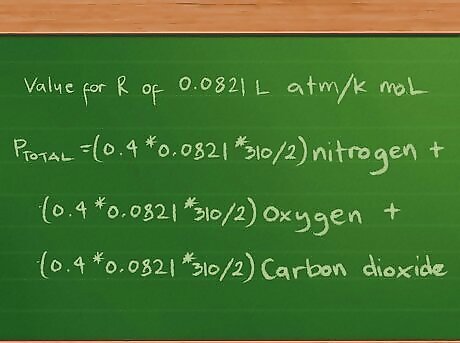

Plug in the value for the constant R. We’ll report the partial and total pressures in atmospheres, so we’ll use the value for R of 0.0821 L atm/K mol. Plugging this value into the equation now gives us Ptotal =(0.4 * 0.0821 * 310/2) nitrogen + (0.3 *0.0821 * 310/2) oxygen + (0.2 * 0.0821 * 310/2) carbon dioxide.

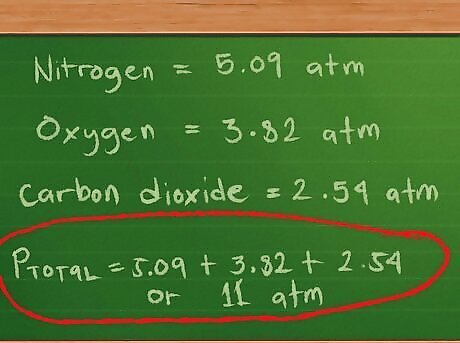

Calculate the partial pressures for each gas. Now that we have the values in place, it’s time to do the math. For the partial pressure of nitrogen, we multiply 0.4 mol by our constant of 0.0821 and our temperature of 310 degrees K, then divide by 2 liters: 0.4 * 0.0821 * 310/2 = 5.09 atm, approximately. For the partial pressure of oxygen, we multiply 0.3 mol by our constant of 0.0821 and our temperature of 310 degrees K, then divide by 2 liters: 0.3 *0.0821 * 310/2 = 3.82 atm, approximately. For the partial pressure of carbon dioxide, we multiply 0.2 mol by our constant of 0.0821 and our temperature of 310 degrees K, then divide by 2 liters: 0.2 * 0.0821 * 310/2 = 2.54 atm, approximately. We now add these pressures to find the total pressure: Ptotal = 5.09 + 3.82 + 2.54, or 11.45 atm, approximately.

Calculating Total, then Partial Pressures

Define the partial pressure equation as before. Again, we’ll assume a 2-liter flask holding 3 gases: nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), and carbon dioxide (CO2). There are 10g of each gas, and the temperature of each gas in the flask is 37 degrees C (98.6 degrees F). The Kelvin temperature will still be 310 degrees, and, as before, we have approximately 0.4 mol of nitrogen, 0.3 mol of oxygen, and 0.2 mol of carbon dioxide. Likewise, we’ll still report the pressures in atmospheres, so we’ll use the value of 0.0821 L atm/K mol for the R constant. Thus, our partial pressures equation still looks the same at this point: Ptotal =(0.4 * 0.0821 * 310/2) nitrogen + (0.3 *0.0821 * 310/2) oxygen + (0.2 * 0.0821 * 310/2) carbon dioxide.

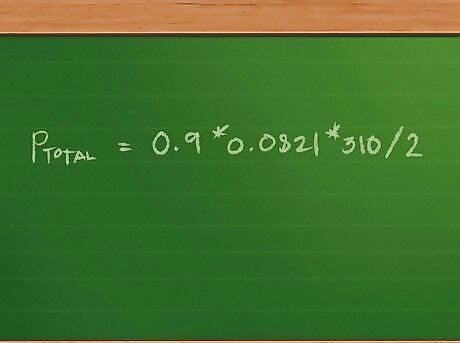

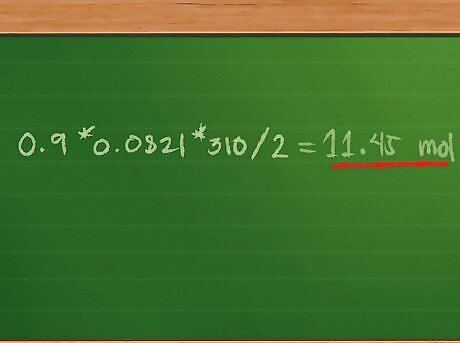

Add the number of moles of each gas in the sample to find the total number of moles in the gas mixture. Because the volume and temperature are the same for each sample in the gas, not to mention each molar value is multiplied by the same constant, we can use the distributive property of mathematics to rewrite the equation as Ptotal = (0.4 + 0.3 + 0.2) * 0.0821 * 310/2. Adding 0.4 + 0.3 + 0.2 = 0.9 mol of gas mixture. This further simplifies the equation to Ptotal = 0.9 * 0.0821 * 310/2.

Find the total pressure of the gas mixture. Multiplying 0.9 * 0.0821 * 310/2 = 11.45 mol, approximately.

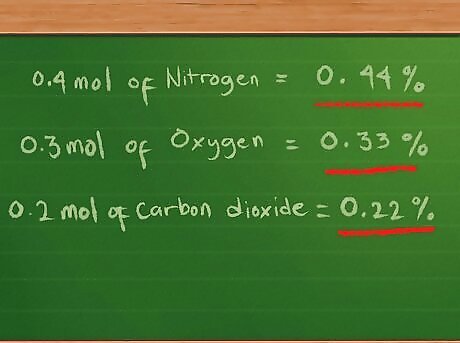

Find the proportion each gas makes of the total mixture. To do this, divide the number of moles of each gas into the total number of moles. There are 0.4 mol of nitrogen, so 0.4/0.9 = 0.44 (44 percent) of the sample, approximately. There are 0.3 mol of nitrogen, so 0.3/0.9 = 0.33 (33 percent) of the sample, approximately. There are 0.2 mol of carbon dioxide, so 0.2/0.9 = 0.22 (22 percent) of the sample, approximately. While the above approximate percentages add to only 0.99, the actual decimals are repeating, so the sum would actual be a repeating series of 9s after the decimal. By definition, this is the same as 1, or 100 percent.

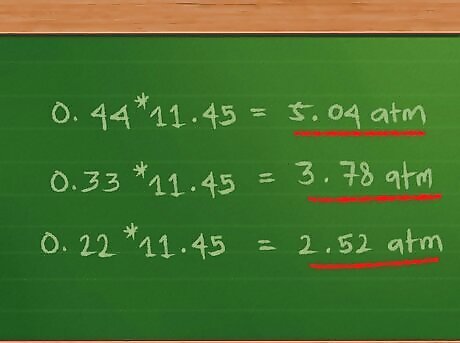

Multiply the proportional amount of each gas by the total pressure to find the partial pressure. Multiplying 0.44 * 11.45 = 5.04 atm, approximately. Multiplying 0.33 * 11.45 = 3.78 atm, approximately. Multiplying 0.22 * 11.45 = 2.52 atm, approximately.

Comments

0 comment