views

A week before its 73rd anniversary, the Chinese state television aired the footage of the day and night drills by the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) along the coast of South China and East China Seas. The PLAN celebrates 73 years of formation on April 23. Formed at Baima (白马, baima), a town under the administration of Gaogang District in Jiangsu province of China, the PLAN has today become the world’s largest navy in numerical terms surpassing the US by 350 to 297.

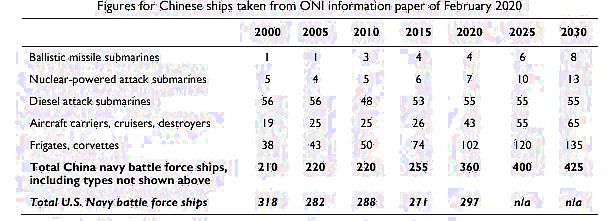

Notably, it was only a 255-ship force in 2015 before China went on a spree of building naval vessels. The Centre for Strategic and International Studies’ China Power initiative highlights that between 2014 and 2018, China launched more submarines, warships, amphibious vessels and auxiliaries than the number of ships currently serving in the individual navies of Germany, India, Spain and the United Kingdom. For instance, 18 ships were commissioned by China in 2016 alone, and at least another 14 were added in 2017. By comparison, the US Navy commissioned only five ships in 2016 and eight ships in 2017. The US intelligence estimates that the PLAN would be fielding around 400 vessels by 2025 and about 425 battleships by 2030 if it continues at the same rate.

Table 1: Number of Chinese and US Navy Battle Force Ships, 2020-2030

Source: ‘China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress’ CRS Report, Updated March 8, 2022

But the credit for making the PLAN world’s largest navy in numerical terms shouldn’t be only given to the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) current regime. Also, unlike what most scholarships on the Chinese navy highlight, it shouldn’t be pinned to 2008 when China moved away from Deng Xiaoping’s model of keeping a low profile (韬光养晦, tao guang yang hui) to a more active framework of “to strive for achievement” (奋发有为, fen fa you wei). Rather, as Rush Doshi highlights in his recent book, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, it is a journey of three decades that the PLA and China’s Central Military Commission (CMC), China’s highest national defence organisation, undertook. He describes China’s approach as Assassin’s Mace (殺手鐧, shashoujian): investing in military tools (also, economic and diplomatic – but not the scope of this article) that are best explained by the threat of the US military intervention in the region and intended to blunt the threat through anti-access/area-denial (sea denial capabilities).

The decision to invest in such capabilities for the PLA in general and the PLAN, in particular, was taken under the leadership of General Secretary Jiang Zemin, especially after the Tiananmen Square incident, the First Gulf War and the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis and the US’ accidental bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade fastened the process. This explains China’s decision to under-invest in carrier aviation, anti-submarine warfare, anti-air warfare and amphibious warfare technologies over asymmetric denial capabilities like sea-mines, the world’s first anti-ship ballistic missile, and the world’s largest submarine fleet in the first two decades since adopting this approach.

China’s Military Texts

After 1985, when former General Secretary Deng Xiaoping changed China’s strategic outlook by declaring that there was no longer a conventional or nuclear war threat with the Soviet Union, China’s navy shifted its strategy from “Coastal Defence” to “Off-Shore Defence”. The Academy of Military Science’s 2013 edition of Science of Military Strategy (SMS) (战略学, zhanlue xue), a core textbook for senior PLA officers on how wars should be planned and conducted at the strategic level, highlights that this is an area (zone) of defence-type strategy and not a blue-ocean offence or coastal defence strategy. Under General Secretary Hu Jintao, this changed when the PLAN started moving towards “Off-Shore Defence” and “Blue-Water Defence.” However, the State Council’s 2015 defence whitepaper categorically demanded the PLA to safeguard the security of China’s overseas interests (维护海外利益安全, weihu haiwai liyi anquan). This was perhaps the first time such explicit demands were made, although the PLA has been slowly moving towards it over the past decade.

Manifestation of Changing Strategy under Xi Jinping

Based on empirical evidence, my upcoming research highlights that China’s weapons and vessels acquisition and commissioning have followed the guidelines described in the 2015 defence white paper. It has slowly moved away from its investment in sea denial weapons and vessels to long-range and strategic vessels like aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, frigates and amphibious warfare technology in the past one and a half decades. However, multiple commentaries in the PLA Daily (解放军日报, jiefangjun ribao) since 2015 have repeatedly noted that China lacks strategic airlift and mid-sea refuelling capabilities, which are the backbone of any blue water, long-range and strategic naval force. Thus, China has also focused on developing vessels and aircraft in the past few years, which would help and support its longer legs on open seas and mid-air. But it is still far away from achieving these targets.

Table 2: Number of Certain Types of Ships Since 2005

Source: ‘China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress’ CRS Report, Updated March 8, 2022

Mao Zedong (毛澤東) had claimed that the PRC would never participate in foreign military exercises and would never have bases abroad. Abandoning his directive, the Chinese military in 2002 began participating in bilateral and multilateral exercises and established an overseas military outpost in Djibouti, its first in the Indian Ocean region, in 2017. Its Djibouti base is critical for securing China’s trade and energy security and is used by Chinese peacekeeping forces in Africa. It is also a vital point of contact for Chinese navy vessels to refuel while conducting anti-piracy operations in the western Indian Ocean. The 2021 edition of the Department of Defence’s annual China’s military power report claims that the PRC has probably considered Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Emirates, Kenya, Seychelles, Tanzania, Angola and Tajikistan as locations for military bases or military logistics facilities.

China’s naval capabilities are not only growing quantitatively but also improving qualitatively. The recent RAND Corporation report highlights that over 70 per cent of the PLAN fleet in 2017 was considered “modern,” up from less than 50 per cent in 2010. Furthermore, the report also underlines that China is producing larger ships capable of accommodating advanced armaments and onboard systems. The first Type 055 cruiser, for instance, entered service in 2020 and can carry large cruise missiles and is capable of escorting an aircraft carrier into blue waters.

Finally, the PLAN is also developing its Marine Corps, which has grown from two to eight brigades since 2017. It is tasked with both its longstanding amphibious warfare mission as well as new missions, including greater emphasis on non-war military operations. Conor Kennedy’s US Naval War College report highlights that under the slogan of “all-domain operations” (全域作战, quanyu zuozhan), the PLAN Marine Corps now regularly trains to operate in new environments, such as desert, cold, jungle and high-elevation training areas. The Chinese military leadership has called on the force “to strive to build an elite force capable of full-spectrum operations, all-domain operations, operations in all dimensions, and emergency operations at all times”.

Impact of Naval Modernisation on Regional Balance of Power

The regional balance of power in East Asia is changing. Admiral Philip Davidson, former Commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, in his 2019 testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee, said that there is no guarantee that the United States would win a future conflict with China (in China’s backyard). Since 2013 China has expanded artificial islands and reefs in the South China Sea and subsequently installed a network of runways, missile launchers, barracks and communications facilities.

Admiral John C. Aquilino, the current US Indo-Pacific Commander, recently made a statement that China has fully militarised at least three of the several islands it built in the disputed South China Sea, arming them with anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems, laser and jamming equipment and fighter jets in an increasingly aggressive move that threatens all nations operating nearby. These advances have led many military personnel, policymakers and analysts to wonder if Beijing has established unassailable control over the disputed waters of the region.

Furthermore, the PLAN’s research vessels have also slowly but more frequently ventured into the Indian Ocean Region since 2019. It aligns with the PRC’s two-ocean approach to maritime security, where it envisions establishing an arc-shaped strategic zone that covers the western Pacific Ocean and the northern Indian Ocean. For instance, the Science of Military Strategy states, “Because our at-sea sovereignty and interests have frequently come under intrusions … we need to form into a powerful and strong two oceans layout in order to face the crises that may possibly erupt.”

As part of its Fiscal Year 2023 budget request, the US Navy plans to decommission nine Freedom-class Littoral Combat Ships, five Ticonderoga-class cruisers, two Los Angeles-class submarines, four Landing Dock Ships, two oilers and two Expeditionary Transfer Docks. A ship-to-ship comparison between the US and Chinese naval forces is highly inaccurate when the world is heading towards smart and intelligent weapons and technology. However, it is a broader indicator of the evolving trend in the Indo-Pacific regional security architecture.

PostScript:

I have observed that the PLAN’s rate of vessel commissioning has fallen in the past two years. Unlike 2019-2020, when there was news about a new naval vessel every 10 days, it is occasional now. Either the Chinese state media has moved away from celebrating every vessel that the PLAN commissions like it did in the past, or security policy expert Dr Sarah Kirchberger’s argument about life cost — taking a toll on the commissioning rate of the PLA — has proven correct. (Her argument: Naval vessel’s average lifespan is around 40 years — Procurement costs only account for 23 per cent of the life cost; operations, maintenance and update costs account for a massive 71 per cent of life cost, with the remaining being fuel and development expenses. Thus, maintenance of the existing fleet slows down the expansion.)

Suyash Desai is a research scholar studying China’s defence and foreign policies. He is currently studying the traditional Chinese language at National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment