views

Conflict is essentially an escalation of a disagreement, wherein conscious beings actively attempt to damage one another (Nicholson, 1992), on account of clashes of interest, opinions, principles (MacDonald, 2009) or even needs (Burton, 1990).

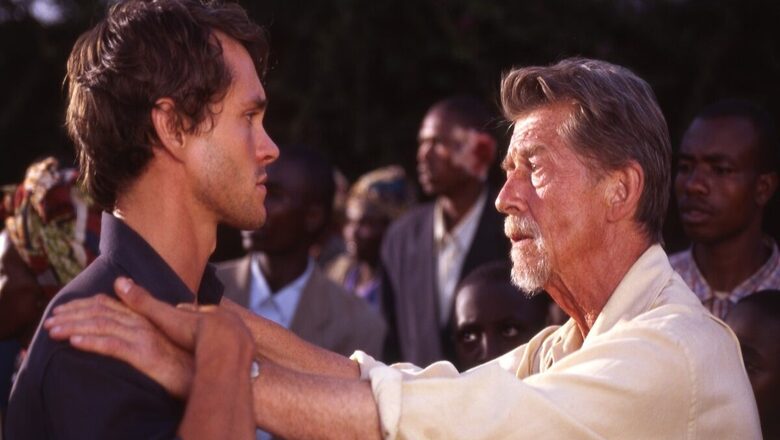

With reference to the movie Shooting Dogs (2005), the crux of the plot is based on the Rwandan genocide, which seeks to highlight the conflict in an in-depth manner, especially when analysed in sociological terms. The involvement of the white-skinned actors is superficially understood and labelled as a ‘third party’ involvement. What is not taken into account, is how third-party intervention and ‘mediation’ is invariably defaulted to mean they are neutral or objective in their outlook and not actively a part of the conflict.

Father Christopher and Joe certainly did belong to the UN, a third-party Track 1 organisation, but were nonetheless personally positioned within the conflict rather than being an outside spectator. Furthermore, mediation is not necessarily something that comes from a third-party entity; it may very well come from someone belonging to either of the conflicting camps. The conflict, especially as portrayed in the movie, is not simply black versus white but also includes the intersecting grey areas because of the French and other whites getting caught up in a conflict that has nothing to do with them directly.

What is of paramount importance in terms of identity clash and classifications, is the very idea of the Hutu versus Tutsi game. Even the classification of what type of conflict it is, becomes hard to discern; is it an inter-community conflict or an intra-community one? Both Hutus and Tutsis come under the ethnic classification of being Blacks and the common nationality of being Rwandans, but the problem that arises is that of the “more European and civilised Blacks” against the “less European and civilised Blacks”, linking back to our reading from Classical Theories in Sociology (Dubious, 1898).

Conflict settlement and its resolution ask for differences and similarities to be identified, but the problem with the Hutus was that while they highlighted what the differences were, there was no acknowledgement of what the similarities might be. The Hutus, a majority, resorted to communal cleansing as a resolution to their problem, with the approach of “no opposer, no opposition” and “no resolution needed when the problem (quite literally the Tutsis, a minority), doesn’t even exist”.

Another scene where this ethnocentric egocentrism is starkly showcased is when the councillor speaks to Father Christopher. The councillor, himself a Hutu Rwandan, says that the “welfare of their citizens is of utmost importance”, completely downplaying the harrowing plight of the Tutsis and simply focusing on the well-being of the Hutus.

This is evident in how the Tutsis are not even considered citizens in the first place, in the movie. This ideology physically manifests in the attempt to annihilate the Tutsis and the resultant loss of many lives.

The media plays a very important role in terms of ideological overpowering and knowledge dissemination. First, the media is not a neutral or objective entity that simply reports information in a passive fashion. Rather, the source of the media house, the ideology that is ‘safe’ to side with and the human elements and personal inclinations of the reporters made a huge difference in how things played out. The news on the radio was a tool to fuel the flames of hatred, with the discourse and wording of the news shaping what the perception of the situation would turn out to be. The survey that was being carried out, and the data that was extracted from it was another resource that facilitated the conflict; the Hutu militia knowing which areas to attack.

The situation where the Tutsis were trapped within the boundaries of the Ecole Technique, was a sort of static deadlock in the situation, where there was no direct physical violence going on, and I personally would call this a temporary ‘management’ of the conflict by the Belgian UN troops. They would prevent the killings as long as their presence existed, but would not actively ward off the Hutu militia threat, basically amounting to a superficial conflict ‘settlement’ where they shove the problematic dust under the carpet instead of actually cleaning it up. Eventually, when the troops pulled out, that carpet vanished and the Tutsis were (again, very literally), ‘cleaned’ out. This conflict ended in a zero-sum game wherein the Hutus achieved their ‘peace’ at the cost of the Tutsi lives.

As mentioned earlier, these parties might mediate a conflict situation, but may not be able to help reach a conclusion. The UN troops were sandwiched between their mandate that dictates the terms of their duties and the limit to the actions they can take as individuals, which begin to light the structural limitations that prevent one from acting in ways that are not already prescribed or accounted for beforehand.

Furthermore, when we talk of structure, what is of noteworthy importance is that most of the government positions were held by the Hutus, which put the Tutsis in a disadvantageous position. The Tutsis were not able to even get away from the structure itself, more than the Hutus, who actually perpetrated the violence and conflict. The positions of authority were majorly in the hands of the Hutus, providing them with authority to generate, exercise and legitimise their power and potential to not only dominate, but also oppress and exterminate the Tutsis. The means to fend for themselves, much less rebel, is unavailable to the Tutsis, creating dependence on the UN troops and UN representatives like Joe and Father Christopher.

Hypothetically, if the conflict had been settled, unless the underlying problems were addressed, it runs a risk of rekindling the conflict. Even if it had been resolved right down to the roots, unless there is a structural change via conflict transformation, which not only resolves the conflict but also maintains the ensuing peace, the conflict cannot really be deemed as being “successfully extinguished”.

A few negotiation techniques were visibly evident in the movie. The first one was where a vehicle came to extricate the Europeans who were stuck in the Ecole Technique Officielle, and Joe tried to use his positionality as someone with white skin who was ‘eligible’ to get saved and escape the conflict. He even tried to offer his privileged positional status by virtue of being a white, to offer help to some other Rwandans who needed it more than him. Another time was when one of the adults begged the fleeing UN troops to at least let the children escape, if not the adults. Both these examples serve as negotiation techniques, in vain.

Towards the final moments of the movie, the lady representative of the United Nations is seen engaging in a word salad, evidently and profusely avoiding controversial words such as ‘genocide’. Using the word genocide would force the UN to acknowledge the fact that the Hutus are engaging in an ethnic cleansing, and hence would be obliged to intervene and seek out conclusions using resources that they could use for themselves instead. Ultimately, even the objectivity of a third party is tainted with subjectivity at the end of the day, and actions are taken in accordance with what suits their narratives and benefits.

The combination of various approaches is necessary for the conflict to be dealt with effectively, which is what was missing in the movie. Instead of transitioning from conflict description and acknowledgement to settlement and then to resolution, the Hutus sought to directly jump onto the resolution front, with no common understanding of the perceived differences by the parties brought to the front table for a discussion.

Yashee Jha, a multi-faceted student, is an avid commentator on various topical issues. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment