views

China has sent a new ambassador to Kabul for the first time since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021. With this, even as it has not recognised the Taliban regime, China has signalled a clear intent to engage with it, in a bid to secure an array of interests including the Belt and Road Initiative, access to Afghanistan’s mineral wealth and keeping Uyghur militants at bay.

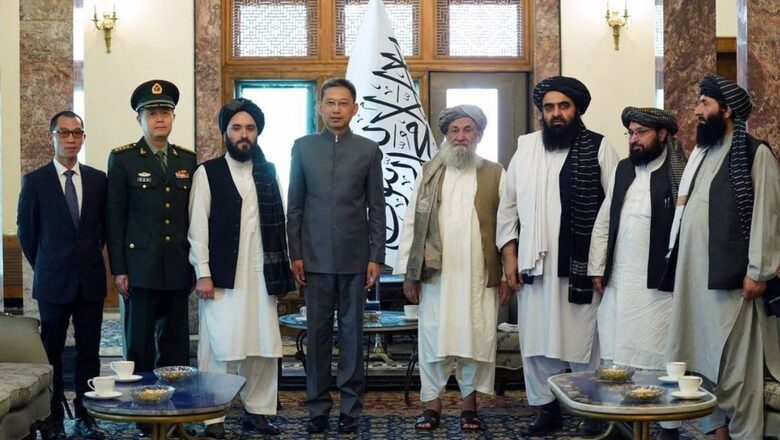

Zhao Xing, the new Chinese ambassador, officially presented his credentials in a lavish ceremony held in Kabul last week. China has become one of at least six other countries, namely Qatar, Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, to have their ambassadors in the conflict-ridden nation. The Taliban seeks to play this up as an endorsement from China and a cue for other nations to step up and formally recognise the new leadership in Kabul.

China asserts that Afghanistan has significantly recovered since the Taliban takeover in 2021. In an interview with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) mouthpiece Global Times, Zhao said that the nation is gradually recovering with the economic and security situations having improved in the last two years.

China has its work cut out in Afghanistan. Beijing wants Kabul to help secure the BRI project at a time when it is losing steam and is likely to be overshadowed by the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IME EC). China also has to deal with the security challenges emanating from the conflict between the Taliban and Pakistan, with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) being a prime target. It not only has to secure the CPEC but also manoeuvre around the Taliban’s heated conflict with Pakistan along the border. It also has to balance ties with Iran, a Shia-Muslim nation with ideological differences with the Sunni-Muslim Taliban, locked in a violent water dispute over the Helmand River. China also has the threat of Uyghur militants to take care of. The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) is being sheltered by the Taliban in Afghan territory, posing a risk of heightened insurgency in the China-controlled Xinjiang region.

In fact, the Taliban threat to China’s economic interests in and around Afghanistan is so extensive that Beijing is locked in a catch-22 situation. If it shuns the Taliban, the risks would only worsen, and if it embraces the militant regime in Kabul, it would embolden the warlords and convey a negative image on the global stage— one where China is seen as complicit in the Taliban’s violent oppression of women and young girls, among other crimes.

However, for now, China has made its choice since there is an opportunity in this crisis as well. Afghanistan sits on trillions of dollars worth of mineral wealth, more than $3 trillion according to one US study. With reserves of gold, oil, lithium, copper, cobalt, various gemstones, chromite, iron and more, the war-ravaged nation is a treasure chest that China may deem worth the risk. Not only is the Afghan Taliban regime desperately seeking investments from global players, but it is also keen on being part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and wants China to resume its mining projects in the country.

China has expressed interest in investing $10 billion in Afghanistan’s lithium reserves. A Chinese company has also signed a $700 million contract to extract oil from the Amu Darya basin. It runs mining operations tapping into the Mes Aynak copper reserves. Afghanistan also announced seven contracts with Chinese and other companies, worth $6.5 billion, which is nearly half of the country’s GDP.

Attacks on Chinese citizens involved in crucial projects in Afghanistan and Pakistan have continued with the Taliban at the helm of affairs. Pakistan has been unable to fight off the threat of the Tehreek-e-Taliban on its territory, and border disagreements over the Durand Line have escalated into full-blown conflicts with the Afghan Taliban turning hostile towards its former patron.

For long, Beijing has leaned on Islamabad to do its bidding with the Taliban. However, Pakistan has taken a backseat in China’s scheme of things, owing to its failure in securing Chinese citizens and interests along the CPEC. It now seeks the cooperation of the Taliban directly and has even agreed to extend the CPEC into Afghanistan. Through this, its mining exploits could now travel through the CPEC and enter the Indian Ocean through the Gwadar port in Pakistan.

China also needs the Taliban to act against the ETIM. Previously, there have been reports of China paying the Taliban to keep the militants at bay. For the Taliban, this is a convenient leverage. The risks are heightened further when one factors in the attacks by ISIS-K, the regional affiliate of the Islamic State group, as well as the opposition posed by the anti-Taliban National Resistance Front (NRF) and internal disputes within the Taliban related to mineral resources.

Last year December, ISIS-K carried out an attack on a Kabul hotel that was frequented by Chinese business people. This incident occurred after a meeting between Chinese Ambassador Wang Yu and Afghan Deputy Foreign Minister Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai to discuss the security of the Chinese Embassy. The Taliban itself has its own fears regarding ISIS-K, particularly concerning the potential for collaboration between militant groups that could weaken the control of the ruling faction. The fight for the Afghan exploits puts into question the Taliban’s own abilities to secure Chinese interests.

So what is the end game here?

There is no easy way to deal with the Taliban but China is taking the risk anyway. China has to juggle between the Taliban, Iran and Pakistan and also secure its own borders. But by being one of the first in line, China may seek the first mover’s advantage. China’s Afghan strategy is taking shape amid intensifying rivalry with the United States. If China can secure a lead in the quest for Afghanistan’s mineral wealth, it could possibly one-up the US in another battleground. It remains to be seen, however, if it will emerge a victor or with its fingers burnt.

Comments

0 comment