views

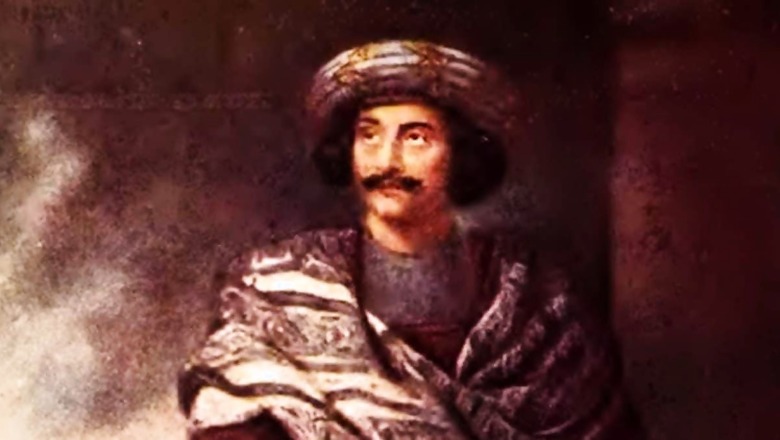

What exactly was Raja Rammohun Roy’s role vis-à-vis the British administration’s introduction of an English education system in early 19th century colonial India, replacing the older system that consisted of a traditional Sanskrit pedagogy? Was he an apologist for Christianity under the guise of a progressive Hindu, or, perhaps even a convert – who had secretly relinquished his forebears’ religion in order to embrace Christianity, the religion of the rulers of his era? Did he present a distorted interpretation of Hindu thought and scriptures before the world? Was it part of the Raja’s ‘ulterior motives’ to Christianise the entire Indian subcontinent and annihilate Hinduism from the land of its birth?

The clamour of such questions and many more, asked in a similar vein, has risen to an almost deafening level, even as we celebrated the 250th (or, perhaps 252nd) year of the Raja’s birth just a fortnight ago. British stooge or not, the Raja has been consistent in attracting controversies and condemnations from a section of his own countrymen, throughout these two-and-a-half centuries that encompass his life as well as his afterlife as a monumental Indian renaissance figure. In stark contrast to these negative reactions and outright denunciations, the Raja has equally been at the receiving end of great adulation and reverence extended to him by some of the best minds that India has ever produced, including Swami Vivekananda, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo.

Such extreme and contradictory attitudes towards the Raja may naturally baffle the 21st-century Indian reader. Partly to alleviate such bafflement, partly to respond to the many cynical questions surrounding the Raja, and thus (hopefully) lay to rest some of the controversies surrounding him, let us not be outright dismissive of the aforementioned questions. Instead, let us consider these questions, cynical and provocative as they may be, at face value – if only to explore them at a deeper level – and find out whether they have any truth to them. And to do that, let us go over the available evidence from the Raja’s life, his times, his written works, as well as some writings about him – including by those who saw him; and then compare all of that with several of the commonly held notions about the Raja and his legacy in today’s time.

Based on these principles and methods of historical enquiry, the present series of articles propose to deal with a number of questions and allegations that surround the Raja’s life and his role in modern India’s history – with the hope that such an exercise might help us better understand our country’s past, as well as its present and future.

What Was Rammohun Roy’s Role vis-à-vis English Education in Colonial India?

A common charge against the Raja is that he was majorly – if not solely – responsible for bringing about a decisive change in the British colonial administration’s policy on education for Indians, whereby the older system of Sanskrit-based traditional education was replaced with the English-based European liberal education, causing Indians to become progressively anglicised and indifferent to their own religion and tradition. This particular allegation against the Raja is hinged on broadly three assumptions, which are as follows:

- The Raja was the only – or at least the most influential – lobbyist for English education.

- It was his intervention, in the form of a letter to Lord Amherst, the then Governor-General, in December 1823, that played a key role in changing the British colonial administration’s attitude towards education policy in India.

- The Raja was prejudiced against the older Sanskrit-based traditional education owing to his ‘poor knowledge’ of Sanskrit and the shastras.

Therefore, to verify the above allegation against the Raja with regard to his role in affecting a crucial change in the education policy of the British colonial administration, let us interrogate the three aforementioned assumptions. Based on the verbal admissions made by well-known products of the liberal system of English education and the historiographical analysis of early 19th-century Indian society by reputed historians, we shall examine whether Raja Rammohun Roy was either the very first proponent, among Indians, of English education, or even the only Indian who advocated for the adoption of the English education (which included using English as a medium of instruction across different levels of education) in colonial India; whether his letter to Lord Amherst was effectual in bringing policy changes; and, last but not the least, whether the Raja was familiar with the Sanskrit language and the shastras written in it, and to what extent.

First things first. Here is a timeline of the British interventions with regard to bringing a change in educational practices in colonial India. At this point, it is important to note, as the renowned Indian historiographer R.C. Majumdar observes, that “the policy of the East India Company was not to interfere in the religious beliefs of its subjects.” In keeping with this policy, the early colonial administration simply encouraged oriental learning. Thus, Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of Bengal, founded the Calcutta Madrasa (or Muhammadan College) in 1781. The objective of this college was to promote studies in Arabic and Persian, as well as Muslim legal studies. A decade later, the Sanskrit College at Benares was established in 1791 by a government official by the name of Jonathan Duncan, who was appointed Superintendent and Resident at Benares by the second Governor-General of Bengal Lord Cornwallis. The stated objectives of this college were the preservation and cultivation of the laws, literature and religion of the Hindus.

The first-ever British intervention in encouraging and/or actively promoting English education in colonial India, through a change in administrative policy, took place much later – in March 1835 – when the first Governor-General of India, Lord William Bentinck’s Resolution on education was issued. This change in policy came about in the aftermath of a series of heated debates in the British parliament, held between 1833 and 1835, on the question of allocating funds to either ‘oriental education’ (i.e., Sanskrit-based traditional education) or the English liberal education. Here, we should note that Raja Rammohun Roy had already passed away in 1833 while visiting England, which made it impossible for him to take part in these crucial debates during the years 1833–1835 that ultimately led to the change in British administrative policy in favour of the English education.

Now, a question arises as to why the debates on education policy picked up momentum in the year 1833. The answer lies in the Charter Act of 1793, which mandated that the Royal Charter given to the British East India Company, for the latter to manage the British territories in India, would be renewed every 20 years – and so it was until the year 1853. At the time of the passing of the Charter Act of 1793, the Christian evangelists Charles Grant and William Wilberforce, both members of the British Parliament, tried their best to persuade the British government to send missionaries and school masters throughout British India, so that Christianity as well as European learning could be spread in that country. In this, they failed utterly.

Thereafter, these Christian evangelists recommenced their efforts at the time of the next renewal of the Charter Act in 1813. This time, thanks to Charles Grant’s Observations on the State of Society among the Asiatic Subjects of Great Britain, a treatise advocating with evangelical zeal the preaching of Christianity among the Hindus, as well as William Wilberforce’s conviction, idealism, and eloquence in the Parliament, the evangelists succeeded in setting up an episcopal establishment in India, and, in addition, “the first grant of one lakh rupees a year [was] set apart, out of the Indian revenue, for ‘the encouragement of the learned natives of India, and for the introduction of a knowledge of European sciences among the people.’” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

However, the money thus sanctioned by the renewed Charter Act of 1813 remained unspent for a long time – a decade, to be precise – until July 1823, when the General Committee of Public Instruction at Calcutta was formed. This Committee was put in charge of the existing government institutions as well as the one lakh grant. The Governor-General of Bengal at the time was Lord Amherst, and within months of the formation of the Committee, an institution of higher learning in Sanskrit and the shastras came up in Calcutta in the form of the Sanskrit College, which was founded in February 1824.

It is at this juncture, that Raja Rammohun Roy comes into the picture. As mentioned earlier, the Raja had written a letter dated December 1823 to Lord Amherst, passionately opposing the proposal to establish yet another Sanskrit institution (prior to this, the government official Jonathan Duncan, Superintendent and Resident at Benares, had founded the Sanskrit College at Benares) and requesting that the funds be utilised for the promotion of “useful Sciences” instead. It is now clear that the Raja’s epistolary protests against setting up yet another institution of oriental learning, out of the Indian revenue extracted by the Colonial government, had fallen on deaf ears – as the Sanskrit College at Calcutta came up anyway, within only three months of his letter being directed to the Governor-General. So much for the role of the Raja’s letter to Lord Amherst opposing Sanskrit education and advocating for English education.

But a more important question to ask would be: was the Raja being exceptional among his contemporary fellow Indians, or, was he the earliest pioneer in desiring and advocating for English education for his countrymen? Far from it – so far as historical facts are borne out by the evidence available in this regard.

By means of a meticulous survey of the various newspapers and journals of the period (i.e., the early decades of the 19th century), R.C. Majumdar has captured, in vivid detail, the genuine and intense public enthusiasm for acquiring English education during the Raja’s lifetime. Majumdar presented his findings in this regard in the tenth volume of his magnum opus The History and Culture of the Indian People, titled British Paramountcy and Indian Renaissance (Part II).

In this fine historiographic account of the socio-cultural conditions of the Indian people during the 18th and 19th centuries, Majumdar traces the public enthusiasm for English education right back to the final years of the 18th century; observing that “exigencies of administration and commercial intercourse” between the native Indians and Europeans, especially the British, were responsible for kindling an initial interest in English education among Indian traders, entrepreneurs and various other professionals. However, what is more interesting as well as significant is that this interest in English education for mere material reasons like administration and commerce, soon turned into widespread enthusiasm for European learning, as educated Indians – especially Hindus – came to realise the value of the English language as the high road to acquainting oneself with European culture.

In the words of R.C. Majumdar: “The more they [i.e., the educated Hindus] came into contact with the educated English people the more they understood the nature and importance of their distinctive culture and realized the necessity of imbibing its spirit through the knowledge of English. Schools for teaching English were accordingly founded in Calcutta and its neighbourhood.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

In this connection, Majumdar notes that this growing public enthusiasm for English education was mainly concentrated in the three Presidency towns of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras since the 18th century or even earlier. He locates the period of the intensification of this phenomenon around the turn of the 18th century – i.e., the years leading to the close of the 18th century and the initial decades of the 19th century. Around this time, many Indian inhabitants of the three presidency towns, especially Calcutta (it being the principal centre of commercial activities and the location of key administrative institutions), came in close contact with educated Englishmen, and thus began to appreciate European culture and learning.

The inevitable consequence of such intermingling and close acquaintance between the Indians and the English was the mushrooming of schools for teaching English. Majumdar informs us that efforts in this direction began with establishing such a school at Bhowanipore in Calcutta in the final year of the 18th century, i.e., in the year 1800. Another school for the same purpose came up at Chinsurah (or, Chuchura, a Calcutta suburb) in 1814.

Within a span of only a few years, a concerted initiative towards the spread of English education was palpable in Bengal, especially in its urban and semi-urban areas. In most cases, such initiatives were jointly led by Europeans and Indians, and these were entirely private in nature, up to 1835 – the year when the government finally took a step towards making and rolling out policies on education with a definite aim to spread English education in India.

As the eminent Indian philosopher K.C. Bhattacharya (1875–1949) puts it, “I do not mean that it [i.e., the entire Western system of education, ideas, and sentiments] has been imposed on unwilling minds: we ourselves asked for this education, and we feel, and perhaps rightly, that it has been a blessing in certain ways.” (Bhattacharya 2011 [1929], Swaraj in Ideas) Such statements are a testament to the popularity of English education among 19th-century Indians and their willingness to adopt it. Bhattacharya’s statement, in particular, assumes a special significance – for it comes from someone as learned and reputed as him, one who was not only educated in the English liberal education system during the 19th century and turned out to be a master of both Western and Indian systems of philosophy, reinterpreting and assimilating the former in light of the latter, but someone who also happens to be the author of a celebrated manifesto for decolonising the Indian mind. Bhattacharya, it would be pertinent to mention here, studied at the Presidency College (previously known as the Hindu College).

Coming back to Raja Rammohun Roy, we get to know that he permanently settled down in the city of Calcutta in the year 1814. However, before he set up his permanent residence in the city, several schools had come up there and were offering courses on the English language and grammar, among other subjects. It is extremely important for us to remember this fact, as it helps us properly contextualise and better appreciate the Raja’s exact role in promoting English education in India.

Having settled in Calcutta, the Raja founded a school near Hedua in North Calcutta (1816). There were 200-odd students studying at this school. In the year 1817, two notable institutions for the proliferation of English education came into being. These are the Calcutta School Book Society and the Hindu College.

The objective of the Calcutta School Book Society “was to make available good textbooks, both in English and in Indian languages, suitable for schools. The society undertook to prepare such textbooks and to print and publish them. [the printing press technology had already arrived in Calcutta a few years prior to this] They were sold at a cheap price and sometimes distributed free.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

The committee members of the society soon “felt the need for good schools for teaching English.” As a result of their initiative, the Calcutta School Society came into being in the year 1818. Its objectives were to “help and improve the schools already existing in Calcutta and to establish new schools according to need.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

It was jointly headed by two prominent individuals: one of them was Raja Radhakanta Dev, who was foremost among the orthodox Hindus of Bengal at that time as well as a leading opponent of Raja Rammohun Roy, and the other individual was the Scottish philanthropist and celebrated clockmaker David Hare, a friend and well-wisher of Rammohun Roy. The composition of the Calcutta School Society’s leadership itself tells us that the Raja was not alone in desiring and promoting English education for his countrymen; he shared this objective with his friends and foes alike.

What was the nature of the Raja’s association with these notable institutions that we just mentioned? In 1817, the year of its founding, the Calcutta School Book Society requested the Raja’s assistance in preparing textbooks. Upon their request, he wrote a Bengali textbook on geography and translated it into English as well. He also translated a pre-existing textbook on astronomy into Bangla and titled it Khagola Vijñāna. We should also keep in mind that among the eminent Indian members of the Calcutta School Book Society was Pandit Mrityunjay Vidyalankar, who would later emerge as a chief theological opponent of Raja Rammohun Roy. Apart from him, Raja Radhakanta Dev was also a notable member of the same society. Despite their presence, the society had sought and incorporated the Raja’s services to achieve its objectives. This close cooperation between the Raja and some of his principal opponents clearly demonstrates that the orthodox as well as reformist sections of Hindus of the time had joined forces in adopting and proliferating English education.

However, as R.C. Majumdar notes, “By far, the most important institution that helped the spread of English education in Bengal was Hindu College [later Presidency College and presently University], established in Calcutta on January 20, 1817.” Let us enquire: what exactly has been the Raja’s role, if any, in establishing this institution of higher learning, which single-handedly produced most of the greatest scientists, historians, archaeologists, philosophers, poets, religious teachers and politicians of 19th and early 20th-century India? We should keep in mind that among its notable pupils were Swami Vivekananda, Rabindranath Tagore, K.C. Bhattacharya, Acharya P.C. Roy, Rakhal Das Banerji, Michael Madhusudan Dutta, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Syama Prasad Mukherjee, S.N. Bose, Meghnad Saha, and former President Dr Rajendra Prasad, among others.

Majumdar discusses the origin of this institution at some length, because, as he notes, “there is a great deal of misconception regarding the foundation of this college.” The ‘misconception’ that Majumdar refers to is chiefly concerning the Raja’s role in setting up this college. Incidentally, Majumdar was himself among the luminaries who graduated from the Hindu (or, Presidency) College.

By perusing documents that are contemporary to the era of the institution’s genesis, Majumdar presents a brief but interesting history of the circumstances that led to its founding. In the process, he concludes that Raja Rammohun Roy can certainly not be counted among those who had taken the initiative to set up this institution. However, the circumstances of the founding of the Hindu College tell us a great deal about the general enthusiasm for adopting English education in place of the traditional Sanskrit or Perso-Arabic education prevalent in that era.

Majumdar writes: “It appears that about the beginning of May, 1816, a Brahmin of Calcutta saw Sir [Edward] Hyde East, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Calcutta, and informed him that many of the leading Hindus were desirous of forming an establishment for the education of their children in a liberal manner as practised by Europeans, and desired him to hold a meeting for this purpose.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

Sir Edward assented to the request and “with the permission of the Governor-General and the Supreme Council, called a meeting at his house on May 14, 1816, at which fifty and upwards of the most respectable Hindu inhabitants of rank or wealth attended, including also the principal Pandits, when a sum of nearly half-a-lakh of Rupees was subscribed and many more subscriptions were promised.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

This account, taken almost verbatim by Majumdar from a letter that Sir Edward wrote to a friend of his, is remarkable – for it reveals that the Hindu inhabitants of Calcutta (and surrounding areas), irrespective of their caste and class, were highly eager to educate their children in the European system of liberal education in English, as early as in the year 1816 – almost two decades prior to Macaulay’s and Lord Bentinck’s interventions in this direction! Majumdar informs us that the Brahmin who first suggested to Sir Edward about the institution was not named in the letter, although Sir Edward mentioned that he knew him.

Many had assumed that this Brahmin was no other than Raja Rammohun Roy, and this gave rise to the myth that the Raja was the founder or promoter of the Hindu College. Majumdar rejects this view, adding that it is “certainly wrong, for later in the same letter, Sir [Edward] Hyde East categorically says that he did not know Raja Rammohun Roy. The Brahmin who saw Sir [Edward] Hyde East seems to be no other than Baidyanath Mukherjee, a well-known citizen of Calcutta at that time.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

Mukherjee went on to become the first secretary of the Hindu College and came to be regarded as one of its founders, as noted by Nagendranath Chattopadhyay, the most well-known Bengali biographer of Raja Rammohun Roy.

What comes out as evidently conspicuous from the above account is that under British colonial rule, the early 19th-century Hindu society – orthodox as well as reformist sections of it – was keen on adopting and promoting English education for their children. And this eagerness was expressed in the form of a private initiative, undertaken by a representative gathering of the Hindu society, irrespective of caste and class, and without any active involvement of Raja Rammohun Roy – whose role in this matter has been confidently ruled out by R.C. Majumdar.

Describing the intensity of Hindu enthusiasm and eagerness for English education, Majumdar further quotes Sir Edward in this regard, who observed: “One of the singularities of the meeting was that it was composed of persons of various castes, all combining for such a purpose, whom nothing else could have brought together; and whose children are to be taught, though not fed, together…Another singularity was that the most distinguished Pandits who attended declared their warm approbation of all the objects proposed; and when they were about to depart, the head Pandit [in all likelihood, Pandit Mrityunjay Vidyalankar], in the name of himself and the others, said that they rejoiced in having lived to see the day when literature (many parts of which had formerly been cultivated in their country with considerable success, but which were now nearly extinct) was about to be revived with greater lustre and prospect of success than ever.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

The above account demonstrates the great desire for English education, even among the orthodox Hindus of the early 19th century. We, therefore, have little reason to put the entire (or even the greater part of the) ‘blame’ or ‘credit’ of ushering in English education in colonial India, squarely on Raja Rammohun Roy, for he was merely symptomatic of his times – a typical representative of the common will for change – at least in this regard. At best, the Raja can be described as one of the most articulate voices advocating for the adoption of English education in place of the traditional Sanskrit pedagogy – a change that was anxiously desired by an overwhelming majority of the Hindu intelligentsia as well as common Hindu parents from various castes, classes, and religious persuasions (orthodox and reformist) of his era. The Raja merely gave voice to this collective early 19th-century Hindu enthusiasm for English education.

Expanding further on his survey of early 19th-century India’s enthusiasm for English education, Majumdar remarks: “Anyone who goes through the newspapers of the period cannot fail to be struck with the genuine enthusiasm which the foundation of these schools evoked in the mind of the public, and a sincere desire to multiply their number in order to meet a keenly felt need for liberal education. There were no less than 25 such schools in Calcutta alone before 1835, when the government ultimately decided to extend its patronage to English education. Large numbers of such institutions were also founded outside Calcutta.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

It must be mentioned that the Raja, like several other private individuals and organisations of his time, founded a school where English, along with other subjects, was taught. Some other notable individuals and organisations, who had set up schools and colleges about the same time, were David Hare, Gaurmohan Auddy, G.A. Turnbull, the Baptish Mission, and the Lord Bishop of Calcutta. The Oriental Seminary, Gaurmohan Auddy’s renowned institution, was set up in 1828. The Lord Bishop’s College came up in 1820. The Christian missionaries of the Baptist Mission established the Baptist Mission College in 1818. They had also set up a school named after Reverend Alexander Duff, who once described the enthusiasm for English education in Bengal in the following words: “The excitement for Western education continued unabated. They pursued us along the streets; they threw open the doors of our palankeens; they poured in their supplications with a pitiful earnestness of countenance which might have softened a heart of stone.” (Majumdar 2018 [1965])

Last but not least, the students who graduated from the famous Hindu College showed great initiative in starting new schools. Majumdar reports that by 1831, as many as six morning schools were being run by the students of Hindu College. All of these schools were founded by them and were being managed by them alone.

One should note that all these institutions mentioned above had come up before 1835, the year when the British colonial administration finally began promoting English education, and the founders, as well as management of these institutions, was fully private in nature. Based on the occasional references found in contemporary sources to the various subjects taught in these schools, Majumdar informs us that they offered courses on mathematics, astronomy, geography, chemistry (both theoretical and practical), philosophy (both Indian and European), history (ancient and modern), painting, handwriting, and various arts and crafts, apart from English literature and grammar.

Founded and run by so many Indians and Europeans, who often collaborated with each other in the early decades of the 19th century to spread English education throughout the country, these institutions played the most important role in bringing about a great transformation in India, and especially in the Hindu society, by fast-forwarding its march out of a medieval era and into modernity. If anything, this transformation gave the early 19th-century Hindu society an edge over other communities in contemporary India – in the spheres of socio-cultural progress, political consciousness, and organisational activities, ultimately giving birth to a renascent nationalism. Whether or not we, applying our present-day perspective which itself is coloured by our own contemporary politics, retrospectively read this radical transformation in the early 19th-century Hindu society as a blessing or a curse, it should be clear in our mind while dealing with 19th-century India and its historical figures, that the historical evidence from that period speaks of a collective social zeal to adopt the European liberal system of education in English, in place of the traditional Sanskrit-based pedagogy.

It would therefore be a grave injustice to historical accuracy to either blame or praise Raja Rammohun Roy for being single-handedly – or even majorly – accountable for ushering in this new education in 19th-century India. Such blame/praise can be equally claimed by other significant historical personalities as well as collective entities, such as Raja Radhakanta Dev, Baidyanath Mukherjee, Pandit Mrityunjay Vidyalankar, Prince Dwarkanath Tagore, Gaurmohan Auddy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, David Hare, Rev. Alexander Duff, Sir Edward Hyde East, the Lord Bishop of Calcutta, Lord William Bentinck, Lord T.B. Macaulay, the Baptist Mission, The Calcutta School Book Society, the Calcutta School Society, the first few generations of the Hindu College graduates, and so on and so forth, for each played their historically significant part in fulfilling the great public desire for English education in 19th-century colonial India.

It is worth reasserting that such personalities and groups represented a variety of social/political/religious interests, they often collaborated with each other on the particular agenda of spreading English education in India; and among such personalities and groups, those of native Indian origin came from both sides of the partisan religious divide, namely, the Hindu orthodoxy and the reformist Hindus.

Thus, we can see why no single individual or entity – be it Raja Rammohun Roy or Lord T.B. Macaulay – can be credited with (or blamed for) replacing the older education system based on a traditional Sanskrit pedagogy with a new liberal education system based on the English language and imported from the European soil. Any credit or blame in this regard goes to the enlightened and rejuvenated sections of the early 19th-century Hindu society, comprising people from various castes, classes, and religious views, who themselves asked for this revolutionary change in the ideals and method of their education.

(To be continued)

Part II will deal with questions concerning the Raja’s relationship with the Hindu religion, its scriptures and knowledge systems, its sacred language of Sanskrit, as well as those concerning his views on the Abrahamic religions.

Sreejit Datta is an educator, researcher and social commentator, writing/speaking on subjects critical to rediscovering and rekindling the Indic consciousness in a postmodern, neoliberal world. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

0 comment