views

The withdrawal of Rs 2,000 denomination notes by the Reserve Bank of India has led to political criticism and recall of the 2016 demonetisation exercise by the government. Legally speaking, this is not ‘demonetisation’ in the strictest sense.

Contrary to the 2016 exercise when Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes ceased to be legal tender and around 86% of the legal currency was flushed out of circulation, the present exercise is limited to Rs 2,000 denomination notes. The central bank had stopped the printing of Rs 2,000 notes in 2018-19.

According to the RBI, the total value of these banknotes in circulation has declined. At its peak in 2018, these denominations made for about Rs 6.73 lakh crore, which made up for about 37.3% of such notes in circulation. As of March 2023, the total value of these notes dropped to Rs 3.62 lakh which constitutes about 10.8% of the notes in circulation.

Simply put, the legality of the move is beyond question after the Constitution Bench judgment of 2023. I must state at the outset that there are clear legal and technical differences between the two exercises. The demonetisation exercise was done under Section 26, Sub Section 2 of the RBI Act of 1934 by which certain denominations ceased to be legal tender. The present exercise seems to be carried out under Section 24, where bank notes of Rs 2,000 have been ‘discontinued’ though they continue to be legal tender.

The wide powers of the central bank or the central government have been recognised in a Constitution Bench judgment vis-à-vis Section 26 under which demonetisation exercise was carried out. By simple deduction, the same logic shall apply to Section 24.

The Reserve Bank of India is the oldest statutory autonomous regulator in India with much impeccable international credibility. The much-talked about autonomy of the RBI and the legal position, frankly, has been in precarious balance for years now. The Supreme Court judgment was not a departure from this duality of sorts.

While the RBI is autonomous in many aspects, wide powers of the central government have been recognised by the Supreme Court to have its sway over various matters, including issuance or discontinuance of currency notes. The view of the RBI is indeed crucial, but history tells us that it has not been decisive in major demonetisation exercises carried out whether it was 1948 or 1978.

The Cut-Off Date

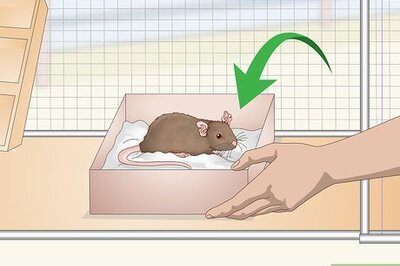

This is not the first time that a move for discontinuation of bank notes has been made. The last such move was back in March 2014. The RBI had then completely withdrawn from circulation all banknotes issued prior to 2005. The only distinguishing factor is that there was no cut-off date for the public to exchange these notes.

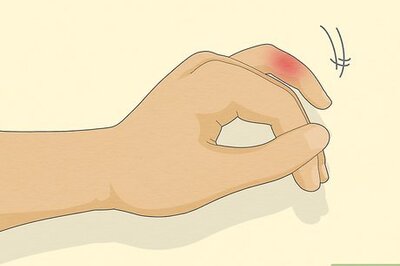

The cut-off date poses two important questions. First, the basis on which this date has been decided. And second, if the discontinuance of these notes is an extension of the exercise of RBI to phase out Rs 2,000 notes, then why should the public be put through any kind of cut-off date. The cut-off date and the limit to exchange only 10 notes at one go (Rs 20,000) gives the announcement an alarmist tone which could have been avoided.

The exercise is clearly more of a streamlining process. The discontinuance of certain currency notes in 2014 or demonetisation of 2016 were clear exercise in political will to flush out black money and target corruption. But the present discontinuation of Rs 2,000 notes cannot be seen in the same vein. The notes were introduced during demonetisation to meet the currency demand. They were part of the solution. So either it could be the acknowledgement of an error while implementing demonetisation or it could be seen as an exercise in streamlining the process started in 2016.

The present exercise opens the government to political criticism and public scrutiny, but there can be no constitutional challenge to this exercise after the verdict of the five-judge bench in the demonetisation case that upheld the constitutionality of the exercise.

Comments

0 comment