views

“We’ve run into a generational gap among the farmers we talk to,” said Dr. Bhure Lal, chairman of the EPCA, speaking mainly of Punjab and Haryana.

The young, he said, understood the hazardous fallout of the farming practice and were ready to change their ways, but the older generation, still the heads of the families and the fields, were not.

This seemed contradictory to the resignation seen behind closed doors.

In a meeting with the EPCA on October 7, Chandigarh, government representatives from Punjab and Haryana threw up their hands in despair at trying to change this deeply ingrained practice, according to those present.

EPCA officials, who have been visiting farmers across districts, trying to persuade them to adopt newer methods and technologies since 2014, too, see no hope of immediate change, till at least the young takes over the farming.

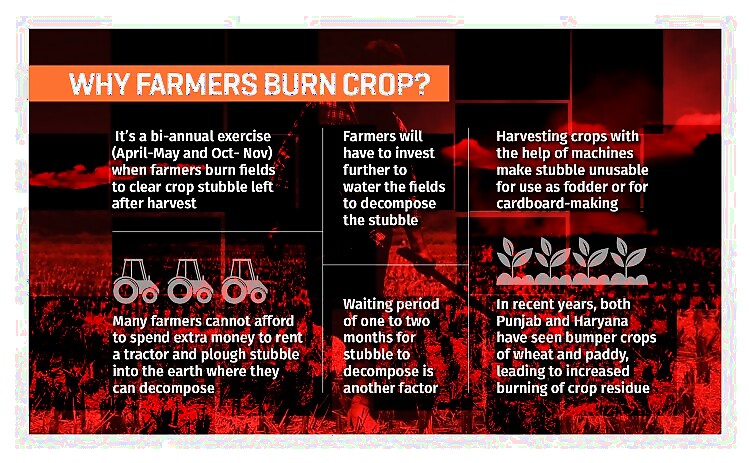

Farmers have been burning stubble for almost 25 to 30 years, estimates Lal, since Haryana and Punjab switched over to paddy. But the damage was never so acute, as seen in the past few years.

On October 30, a Centre for Science and Environment report notes, “Crop burning in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh became more aggressive,” as seen in the images of NASA’s fire mapper.

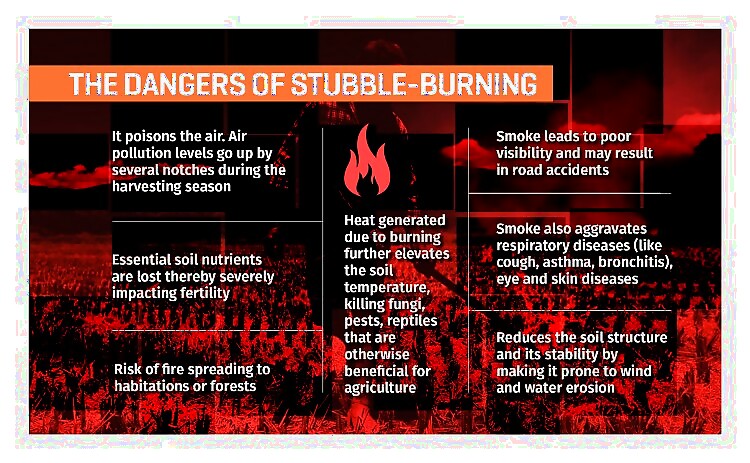

Apart from the smoke that billows monstrously towards Delhi, burning paddy straw causes harm to friendly insects in the soil, it lowers soil fertility and leads to carbon deposits in the soil. The young understand this, discovered Lal in his interactions.

He recalls the innovative tools created in in areas such as Ludhiana — a machine called ‘bhaiya’ that turns off the irrigation pumps on time, saving water and electricity, named after the ubiquitous bhaiyas who once did all such odd jobs.

“If you plant wheat late after November 30,” he explained, “the yield of wheat goes down one quintal per hectare per week.”

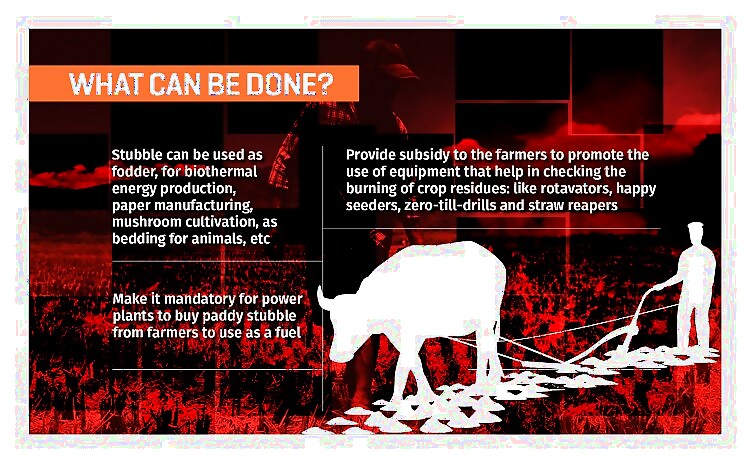

All the methods that the EPCA and other environmentalists have been suggesting are time consuming. It takes two to three days to use tools such as the rotavator, then the happy seeder and then the chopper to clear the field, irrigate the land and chop the paddy straw into small enough pieces that it can mix in the ground and convert to fertiliser. The farmer also has to invest in more water and diesel to operate his tractors, to go through this process, not to mention about Rs 600 per acre. The conversion of paddy straw to fertiliser also takes 45 days, too long to benefit the rabi crop that comes next. The window period between kharif and rabi, Lal says, is only two days.

The government has also subsidised expensive tools such as rotavator and happy seeder, which costs one lakh each. Lal has recommended farmers be organised into cooperatives that buy these machines, so that each one doesn’t has to bear a mammoth cost.

However, he pointed out, there is a need to change agricultural patterns from the dependency on high paying paddy and wheat. Before paddy became popular as a cash crop, more area was used to cultivate maize, jowar bajra. More crops, such as dal and mustard, need to be covered by the government’s minimum support price, to wean farmers away from paddy.

Till then, as evidenced, neither fines and prosecutions in Haryana, nor ongoing awareness campaigns have made much of a dent.

Comments

0 comment