views

New Delhi: A lot has changed in the past four years. The Congress government at the Centre and Samajwadi Party government in Uttar Pradesh have been replaced by the BJP. In this timespan, news cameras have moved on from Muzaffarnagar to Saharanpur and Gorakhpur, covering one tragedy after another. But about 1500 days later, little has changed for over 200 riot affected families in Muzaffarnagar, who are living like refugees in their own land.

Tension was running high in September 2013 in Muzaffarnagar after a Muslim boy and two Hindu boys were killed after an argument. The police failed in stopping a large gathering of local Jat leaders and soon mobs turned violent. Over 60 people were killed in the next three days, forcing thousands of families, mostly Muslims, from about 140 villages to flee their homes and take shelter in relief camps.

On October 26, the state government announced it would provide a one-time compensation of Rs 500,000 for relocation and rehabilitation of families from nine worst-affected villages.

People living in the relief camps were asked, as a precondition to the compensation, to sign an affidavit saying they would not return to their villages.

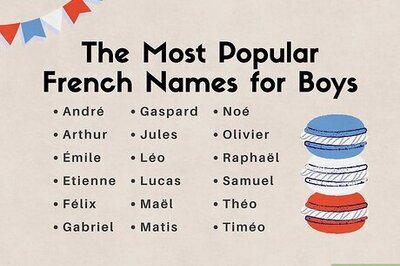

According to government records, 980 families in Muzaffarnagar district and 820 families in Shamli district have received such compensation so far. But about 200 families are still living in relief camps. In several cases, authorities have denied compensation, citing technical reasons like clerical errors; in others, the families have accused local politicians and bureaucrats of corruption.

In a report, Amnesty International has looked into living conditions of these families. Between August 2016 and April 2017, Amnesty International India and AFKAR India Foundation, an NGO based in Shamli, visited 12 resettlement colonies, met 65 families and analyzed the documentation of 190 families who are still struggling to survive.

The researchers found many of these families live in horrific conditions in so-called relief colonies, with little access to water, sanitation, electricity and housing.

The Uttar Pradesh government has failed to meet its obligations under international and Indian laws to provide adequate remedy and reparation and protect the human rights of those displaced in 2013.

Many families were denied compensation by authorities who claimed — despite evidence to the contrary — that they were part of a larger joint family which had already received compensation.

In Uttar Pradesh, as in many other parts of India, households that live under the same roof are demarcated as separate units depending on whether they use a separate kitchen.

The Census of India defines a household as “a group of persons who normally live together and take their meals from a common kitchen”. The census definition states: “The important link in finding out whether it is a household or not, is a common kitchen. There may be one member households, two member households or multi-member households.”

The chief development officer of Muzaffarnagar district also told Amnesty International India that the state government defined a family using the same concept. He said,“A family unit hinges on the idea of “ek chhath aur ek chulla” [one roof and one stove]. There can be many variations to this but if a house has a kitchen then it is considered as a separate household.”

However, several families say that they were denied compensation despite having separate kitchens, and often having ration cards indicating that their addresses were different from those of their relatives.

img src="https://images.news18.com/ibnlive/uploads/2017/09/imag1.jpg" alt="imag1" width="100%" class="alignnone size-full wp-image-1513843" /> (Source: Amnesty International India)

Amjad Khan, for example, used to live with his parents, three brothers and a sister in Mohammadpur Raisingh village. Their house had a common entrance, and separate rooms for each nuclear family unit. Importantly, the parents and the brothers all had independent cooking arrangements and used different stoves. The absence of a common kitchen signified that they were separate households.

However, while Amjad Khan’s father Nawab Khan received Rs 525,000 as compensation in 2014, all the four brothers say they were verbally told by different government officials that they would not receive any money as they were part of the same family. The brothers say they have filed several applications but to no avail.

A number of families spoke out how in spite of having government identification documents such as ration cards and voter identification cards with different addresses from their family members, they have also been denied compensation.

Due to denial of compensation, several of them have been unable to afford education and healthcare for their children, and continue to live in squalid conditions. “Our good times have been pushed back by 10 years to 15 years. We cannot provide for the future of our children.” Amjad Khan displaced from Mohammadpur Raisingh village, now lives in Hussainpur colony with his wife and children.

“My husband died worrying about his family. We haven’t got any compensation, we have no house and live in a makeshift space. I have to look after my children now and it’s very difficult to find a job. We are in a lot of debt: how can I repay it? Some days it’s difficult to buy any food and we sleep hungry. If anyone falls ill, what will I do? How will I afford treatment?” says Sammina Latif, who lives in a settlement with her three children.

Human rights activist Harsh Mander, who has worked to defend the rights of the survivors, has questioned the basis of selecting just nine villages. He told the Amnesty India that “By selecting only nine villages, the state administration showed a callous disregard towards the riot survivors. The government selected only villages which saw significant loss of life and property. It ignored villages where people fled their homes because of fear and where people left their homes because they were ransacked or burned down.”

Comments

0 comment