views

iPods were a lot of things back at their peak – status symbols, the icon of a liberalising music economy, and an excellent gadget by itself. But, tell someone that the sassy music player may have also been modded into a secretive radiation detector – a modification that Apple founder and then-CEO Steve Jobs himself may not have known about – and the story gets rather exciting. It is this story that ex-Apple software engineer David Shayer narrated, almost 15 years after having worked on this top secret project with two external contractors.

As Shayer narrates, his then-boss, who was the director of iPod software, had instructed him to start working on an unofficially sanctioned project. Shayer’s task was to help two engineers affiliated to the United States Department of Energy (DoE) in building a specific custom modification on the iPod. This, as he goes on to explain, would require installing an unspecified type of hardware inside retail models of the iPod, and modify the iPod’s operating system to read the data recorded by this piece of hardware. However, the trick was that all of this should happen entirely in the background, without the data showing up anywhere, including when the iPod would be plugged into a PC for data transfer.

Shayer was reportedly the second ever engineer that was hired to work on iPod software, and hence had the most amount of expertise with iPod software barring the then-director of iPod software (who was incidentally the first engineer recruited in the iPod software team). As he explains, he had worked on almost every bit of the iPod software barring the audio codecs. He began work on this project by allowing access to two engineers, “Paul and Matthew”, to the highly secured iPod division at Apple initially as guests, and subsequently as vendors. They were not assigned access to internal Apple resources, but instead, sourced their own computers and were handed over a copy of the iPod software – based on which they began work on the project.

Subsequently, the two engineers, who were employed by a DoE contractor, Bechtel Corp, got around to working on modifying the source code of the iPod OS. Their need, as they revealed partially to Shayer later in the project, was to install a piece of hardware within the body of the 5th generation iPod, which they succeeded at. The next step is where Shayer stepped in – his job was to help them design a hushed way to record the data that this hardware would generate, which in turn led to creating a hidden partition on the iPod’s 60GB hard drive. He then worked with Paul and Matthew to place an unassuming entry on the iPod’s menus, using which the engineers could simplify the way to control when the hardware would record data on to the hidden hard drive partition.

This, Shayer writes, was possible then because Apple was still not digitally signing its operating system, so the boot kernel (the controller responsible for checking the software before allowing the iPod to work) could load modified operating systems on the music player. To amplify the secrecy of the project, he says that the engineers most likely never approach Apple’s corporate division for official favours, hence playing the entire project on a hushed tone. Soon after they achieved the requirements, the Bechtel engineers, Paul and Matthew, packed up all their belongings and left the Apple premises, leaving a copy of their custom-written operating system with Shayer.

Reading this, years later, Shayer claims that the signs are pretty strong that what they built was a Geiger counter chip into the 5th generation iPod’s body, which they used as an unassuming radioactivity detection tool that would not attract any undue attention in public spaces. As Shayer explains in his post:

My guess is that Paul and Matthew were building something like a stealth Geiger counter. Something that DOE agents could use without furtively hiding it. Something that looked innocuous, that played music, and functioned exactly like a normal iPod. You could walk around a city, casually listening to your tunes, while recording evidence of radioactivity—scanning for smuggled or stolen uranium, for instance, or evidence of a dirty bomb development program—with no chance that the press or public would get wind of what was happening.

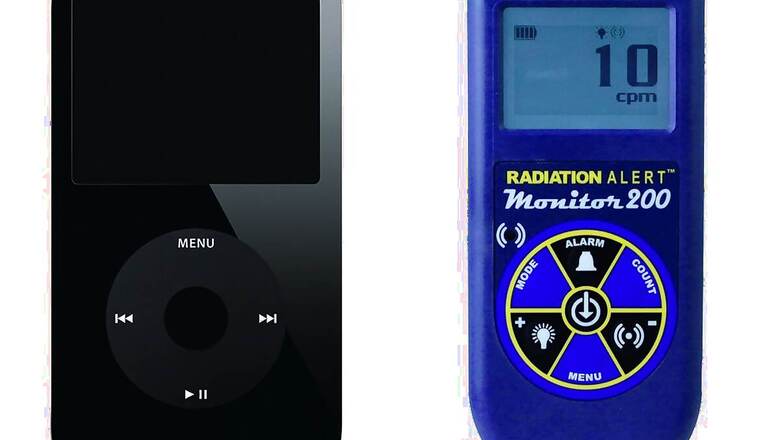

He even found a sample Geiger counter online, the Radiation Alert Monitor 200, which in many ways does resemble the general design of the iPod that Paul and Matthew had used to build their secret tool. Such a tool, it can be assumed, could have proved critical to undercover agents working to find any activities of terrorism in USA. This was about four years after the fatal 9/11 attacks in USA, and defence officials and intelligence agencies would have been active around the clock to find any trace of illegal radioactive material supply, or work on a secret nuclear bomb that may have been happening in USA back then. Further strengthening the credentials of Shayer’s claim is that no official trace of such a project exists in Apple’s archives.

In essence, this little piece of modification to the iconic music player actually turned it into a real life James Bond gadget. An everyday equipment – transformed from within to lend superpowers that can bring down mighty assemblies. Radioactivity, no matter how slyly hidden, always leaves behind traces and signatures that are picked up by devices such as Geiger counters, which further makes it plausible that what Shayer worked on may have helped US intelligence agencies foil attempts of nuclear terrorism in the country.

Comments

0 comment