views

The discourse around the assembly elections in West Bengal has been reduced to just two variables: can the BJP consolidate the Hindu vote and will the TMC’s Muslim vote split?

In the increasingly polarized political landscape of the state, the electoral strategies of the Trinamool Congress (TMC) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are much the same: consolidating their respective religion-based votebanks while hoping to splinter their opponent’s.

No party can claim to represent the state’s historical secular ethos, with the Left-Congress third force having allied with Muslim cleric Abbas Siddiqui’s far-right Indian Secular Front (ISF). The Congress rationalisation that the Left alone has tied up with the ISF has few takers, given that it is in alliance with right-wing parties in other states.

If the Left-Congress has Siddiqui, the BJP has Yogi. Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath commenced a high-voltage campaign in the state on Tuesday, underscoring all the touchpoints of cultural nationalism, including ‘Jai Shri Ram’, ‘love jihad’ and cow smuggling.

The upsurge of identity politics in a state hitherto free of divisive rhetoric is being attributed to the aggressive wooing of the Muslim community by West Bengal CM Mamata ‘Didi’ Banerjee over the last decade, thereby creating space for the BJP’s politics of Hindutva.

In Bengal, the BJP won 57 per cent of the Hindu vote and 40 per cent overall in 2019, and now expects to leverage the Triple Talaq Act, the abrogation of Article 370, the foundation of the Ram Janmabhoomi temple and the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), along with the ‘Muslim appeasement’ trope.

ALSO READ| Days of ‘Khela’ and ‘Boma’: What Bengal Needs is an End to Decades of Political Violence

Going strictly by numbers (based on the 2019 Lok Sabha results), however, it’s advantage Didi. Overall, the TMC won 22 seats and led in 164 assembly segments, well ahead of the halfway mark of 147. Although it lost North Bengal and the South-West to the BJP, it swept the South, where it won 19 seats translating into 138 assembly segments.

Retaining its dominance of the South means hanging on to the 65 per cent Muslim voteshare it secured in 2019. Overall, the minority community accounts for 27 per cent of the state’s population and can influence the outcome in over 100 assembly seats.

The advent of Asaduddin Owaisi’s AIMIM (All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen) in West Bengal is naturally a cause for worry. He has deployed his five Bihar MLAs as observers in constituencies bordering their state, where the minority population exceeds 25 per cent. As a counter, Mamata Banerjee has reached out to RJD leader Tejashwi Yadav and Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav.

The ISF won’t field candidates against Owaisi, but even so, a two- or three-way split in the minority vote—between the TMC, the Left-Congress and the AIMIM—seems inevitable.

In terms of caste, the BJP again benefits from Mamata’s break with the identity-agnostic politics of the Left. The CM had seduced the influential Dalit Matua community, Partition refugees who account for an estimated 17 per cent of the population, away from the Left, but they are now gravitating towards the BJP.

The CAA has accentuated the process. Home Minister Amit Shah has been at pains to allay the Matua community’s disappointment over the slow rollout of the Act (and suspicions vis-a-vis the NRC) by promising fast-tracked citizenship after the Covid-19 vaccination drive.

The BJP’s outreach to the OBCs, Dalits and STs—it holds 7 of the 12 parliamentary reserved seats—seeks to create a composite Hindu identity in the face of Mamata’s sub-nationalism and anti-outsider rhetoric. Subsuming the Bengali identity into the Hindu fold is a challenge—hence, the appropriation of icons like Netaji and Rabindranath Tagore, and the harping on Bengal as the birthplace of Hindu nationalism.

Mamata has countered the BJP’s moves at every step, through focused outreach to relatively small but electorally significant marginalized communities. Like the BJP, she is courting the Matuas and Rajbanshis (an influential ethnic group in north Bengal). She has also followed a policy of welfarism, her latest programme being doorstep delivery of benefits under various government schemes.

But the ground has shifted for the TMC since 2019. For one thing, it is hamstrung by mass defections to the BJP, including heavyweights such as former minister Suvendu Adhikari and Lok Sabha MP Sunil Mondal, not to mention more than a dozen sitting MLAs. Adhikari’s clout in South Bengal is such that the CM has sought to contain him by contesting from Nandigram rather than Kolkata.

Another negative is the unpopularity of her controversial nephew and Lok Sabha MP Abhishek Banerjee, who has been cited as a primary cause of dissent within the TMC, enabling the BJP to play the ‘dynasty’ card.

Then, there are the financial scandals that erupted during the TMC’s watch, such as the Saradha scam and the Narada sting. Apropos the coal scam, regulatory agencies recently questioned Banerjee’s wife and raided several businessmen in the state. Meanwhile, the TMC is said to be facing a resource crunch.

ALSO READ| Battle for Bengal Witnesses a Tech-Tonic Shift as TMC and BJP Go All Digital Guns Blazing

Also working to the TMC’s disadvantage is the eight-phase polling schedule, intended to minimize the political violence for which the state is justly notorious. Polling begins in North Bengal and a BJP surge in its stronghold could influence voters in other parts of the state.

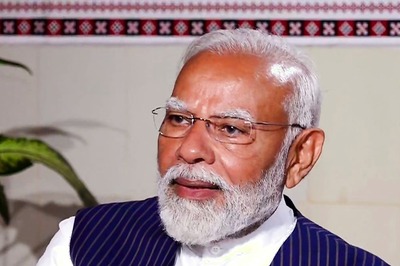

Much is being made of the absence of a BJP ‘face’ against Didi, but the party rarely declares a chief ministerial nominee beforehand. In terms of personalities, it will be Modi versus Didi. Pluralism is a thing of the past; parochialism and cultural nationalism are in vogue. It all boils down to whether the ‘Hindu Hriday Samrat’ can trump the ‘Daughter of Bengal’.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here

Comments

0 comment