views

Paul Samuelson, the first American economist to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences once remarked: “I think that it’s more important for an economist to be wise and sophisticated in scientific method than it is for a physicist because with controlled laboratory experiments possible, they practically guide you; you couldn’t go astray. Whereas in economics, by dogma and misunderstanding, you can go very sadly astray.”

Unfortunately, modern day economics has become significantly more dogmatic than the exact sciences. This is partly out of the normative urge of the discourse-squatting elites to always be right.

More importantly, the application of infallible dogmas allows international bureaucracy, often aligned to Bretton Wood institutions or their offshoots, to shepherd developing economies in the direction developed countries want.

Today’s developed countries traversed a certain socioeconomic and political path before they got to this equilibrium stage. However, this present-day dominant position affords their self-serving army of economists and institutional academics to set ‘ideal rules of economic behaviour’ for other countries.

Such rules completely disregard the agency of self-determination of the developing countries in choosing their own paths.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the criticism of the use of trade tariffs by the developing countries, especially India. And what’s worse, criticism of India’s efforts towards reindustrialisation are mostly fact-free.

India is often characterised negatively for using import tariffs. The dogmatic view that exists like some supreme incontestable truth in economic commentary is that high tariffs are bad and low tariffs are good. What is overlooked is that tariffs are an instrument of sovereign policy towards specific goals – say developing local manufacturing ability. However, these oft-repeated allegations are not even borne out by rather easily available data from the World Trade Organization.

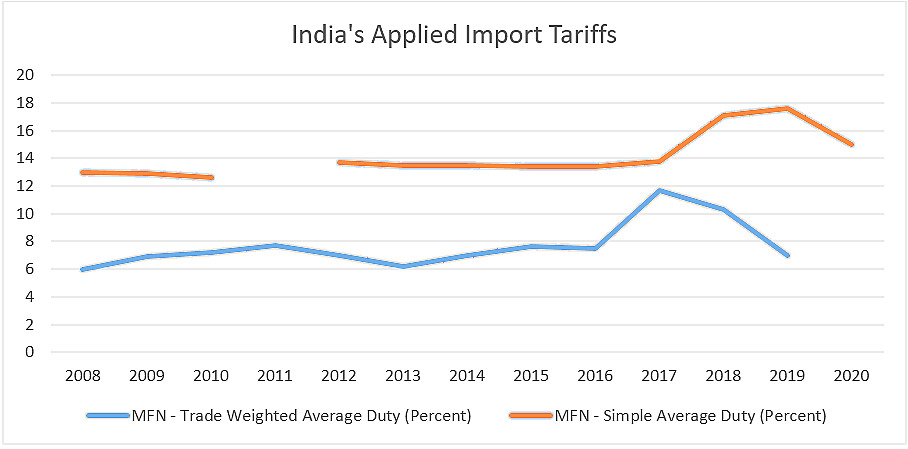

Let us look at India’s applied tariffs. These are the duties actually imposed in a given year by a WTO Member.

The above chart shows that simple average duty which is applied on most favoured nation principle as per the agreed WTO procedures, only spiked once in the recent times and has since been reducing. Similarly, the trade weighted average duty is even clearer – India continues to be in the 6-8% range maintained over several years.

Even this range-bound trade weighted average duty is slightly inflated currently due to contribution from gold. Gold forms almost 9% of all Indian exports and since 2019, the government has been imposing 12.5% duty on the commodity. If the overall trade weighted duty was 7%, ex-gold imports, India’s effective duty rate would come to 6.3%. This is hardly a level that deserves running critical commentaries as has been the case in recent times.

The one year when Indian tariffs did rise in 2017 was the turning point for India in two ways. For the first time, India started viewing trade as an instrument of foreign policy – something every western country has done for time immemorial. India’s trade deficit with China peaked at $73-billion in 2016-17.

India took a geopolitical view of the situation then taking specific measures to arrest this one-way traffic. The trade deficit with China has since steadily come down, though the Covid-19 years may see some fluctuations to the trend of the three years before the pandemic.

Secondly, India started to build capabilities in electronics exports. This category accounts for 30% of all global exports – a great opportunity for India. The preachers of free trade dogma never explain why India could not be a mobile manufacturing industry despite having low import duties pre-2016 and Free Trade Agreements of some nature with electronics powerhouses ASEAN, Japan and South Korea.

As per the booking theories, low duties should have goaded Indian industry to become more competitive, especially with a huge domestic market also available.

Nothing of this sort happened, until the government intervened to start Make in India focus for electronics and mobile. Since then, India has become an exporter of mobile phones. Global firms like HP are beginning to make computing equipment in India. Apple and Samsung – two global leaders will make $5-billion worth of mobile phones this year in India. This shift happened with calibrated, strategic use of tariffs.

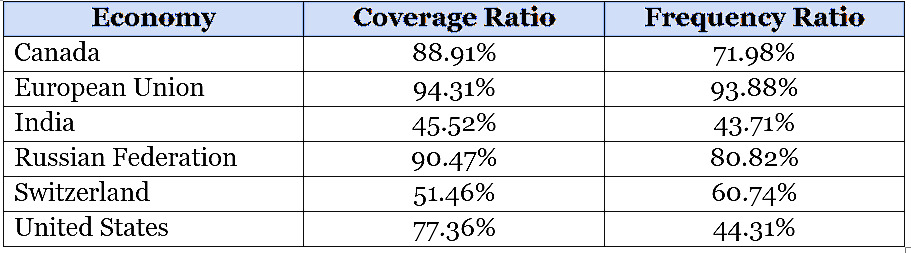

Trade barriers go beyond tariffs – non-tariff measures (NTMs) by used by all countries. These are hidden costs to trading partners of a country.

As per World Integrated Trade Solution or WITS database of World Bank chronicling impact of NTMs, the Coverage Ratio depicts value of imports subject to NTMs relative to total imports and the Frequency Ratio is defined as percentage of traded products to which one or more NTMs are applied. The below table depicts these two key measures for different economies.

Relative to developed countries, India’s NTMs are far lower, both in terms of number of products they are applied to and the volume of trading. India does not erect unnecessary non-tariff barriers like our trading partners do. But this is hardly ever highlighted in any discourse on relative attractiveness of trading rules.

Developed countries protect their own industry through NTMs erected in the name of environment, labour and public health. European Union is erecting carbon border taxes in total disregard to the fact that its constituents – several colonial powers which exploited Asia and Africa to the hilt – are responsible for the stock of global emissions from 1850s to date.

Trade and foreign policy have always been intertwined. The British used free trade because it suited their colonial business model of monopolising global raw materials and then shipping duty-free finished consumption goods to their dominions and beyond.

The United States of America, on the other hand, used tariffs to help industrial growth. The McKinley Act and the Smooth Hawley protectionist measures are well documented. The American industry view shifted from being pro-tariff to pro-free trade only after the manufacturing capacity of all their competitors was decimated post the second world war.

The UK or the USA used contrary approaches to tariffs to gain but in different ways, without academic good versus bad debates. India today is similarly using tariffs as a contraption for current policy imperatives.

Indian commentariat needs to come out of template mindsets, which simply take today’s developed country discourse and apply them as best applicable theory for contemporary Indian interests. Economic destiny has a path dependency and the Indian policy-makers are working to create a model that works for us. While we learn from the world, we should be confident enough to not confuse learning with aping.

For the first time since independence, India is giving itself a realistic chance to develop a credible, non-protectionist, local strengths-driven manufacturing ecosystem. We may use low tariffs when they support this end objective. Let dogmas guide, not dictate our economic policy.

Nimish Joshi is Director, Smahi Foundation of Policy and Research. He writes on public policy and governance. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment