views

Nandita Das’ Manto released in India on September 21 and has got critics praising it for its hard hitting central theme.

I caught up with Das during the film’s premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival earlier this month where she talked about censorship, Section 377 and how things have changed for women in films.

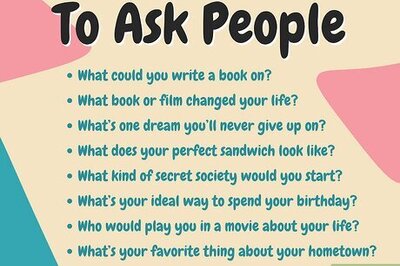

You have always been fighting against censorship…

Yes, twenty two long years! It is always difficult to look around and see the stifling of freedom of expression, and the fight to attain it. Having gone through it myself, with Water, with Fire, I have fought against official forms of censorship, which are bad enough. There are these self-proclaimed custodians of culture who decide what we should be watching, reading, and wearing. And then we also constantly battle self-censorship! A lot of artists, writers and thinkers are being over-careful, not wanting to step on anyone’s toes. They are fearing attacks and not speaking up!

Did that inspire you to a make a film on Saadat Hasan Manto who had a life-long struggle with censorship?

All my films are very personal, whether it is Firaaq or Manto. Both have come from my personal angst of seeing what is happening around me and the desire to respond to them.

I am so glad you brought up Fire. With Section 377 being scrapped, how do you feel vis-a-vis being a part of a radical film like that, way back then.

We still have a long way to go with the rights of trans-people but this is a great step. To be honest, making Fire now would’ve probably been even tougher. There were people telling Deepa Mehta that with this film, she was going to “make” women lesbians! But there was also a huge movement against the censorship; there were rallies and protests that demanded that the film be shown. I am not sure that would happen today. In hindsight I feel that because Fire came under so much attack, we were forced to stop ignoring female homosexuality and began to talk about it in a public space.

For you, is there a differentiation between an artist and their art or the artist and the person?

There has never been that distinction in my life. Sometimes, maybe to my own detriment! People keep asking me if I don’t want to do “fun” films. It’s not like I am a not a humorous person but it’s just that that I see the medium of films as a means to an end. When I have the privilege to use it to say something, I must say something meaningful.

Firaaq (2006) came about in a very crucial time in the political history of India and Manto is being released in another crucial time. What inspires your creative process?

It’s uncanny! I wanted to make a film on Manto’s stories back in 2012 but I didn’t know that I would end up making a film on his life and his politics. But living in these times where identity politics is being used to play a dirty game to divide people on the basis of their nationalities, religions, castes and colour, I had to make a film that speaks to all this. The rising threat to freedom of expression obviously pushed me to move the focus of the film from Manto’s stories to his life, although one can barely differentiate between the two.

Manto also comes out at a time when people are trying to other-ise Urdu as a language and as a larger culture system, and trying to invisibilise it…

Yes, because Urdu is suddenly being seen as the language of the Muslims whereas a language intrinsically belongs to a region and not a religion! It is an Indian language and a whole body of culture born within this country whose history you can’t erase by writing names of roads in the Devanagari script. This project of sudden Hindi-isation is rather short sighted and ill-informed.

You have worked with education policies and you’ve briefly been a teacher too. Did that alter your perspective of viewing history as a monolithic, uni-dimensional entity?

There can never be one idea of a person or a time, there has to be several histories, several narratives and multiple perspectives. Manto is not a biography that is a collection of dates and facts, I didn’t want it to be a Wikipedia page. I did not sit around watching other great biographies learning how they are meant to be told because sometimes it frees you up when you are not restricted by the grammar of filmmaking. I have not read everything Manto has written or everything that has been written on him. I have read a lot but not all because I didn’t want to restrict my narrative by all these other narratives. Yes, I depart from the “truth” of events sometimes in the way I narrate the film, because that’s how my story organically evolved. Perhaps that’s how Manto’s life evolved too; the lines were always blurred between facts and the fiction he was writing.

How much of Manto is “real”?

I would say 95%. Of course, there is no way I could know what Manto and Safiya said to each other in bed so that is where I invent, imagine and create. I became so close to his family that I personally felt that I owed it to them to keep the film as authentic as possible. Restoring histories takes a lot of weaving and the story grows from all sides.

You spoke at the Share Her Journey rally this morning, speaking for the inclusion of more and more women within all sections of the film industry. How do you relate that to the Hindi film industry?

The sexism is of course more under your skin in India, less of the black and white data that you see in Western film industries. Which is why movements like Time’s Up and #MeToo have not been able to make a big dent in the film industries back home. They’re still sadly, little whispers in corners and have not been able to make as much an impact as they should have. Not because there are no men like Weinstein in India but because sexism has been normalised and there is an overarching fear that the women who speak up, will be ostracised. But this is a great place to start, I was a part of something very similar at Cannes and it is amazing how these festivals foster a sense of sisterhood.

Do you see a difference in the way things might have changed for female filmmakers in India, between Firaaq and Manto?

There are a lot more younger people, especially younger women, who are now making films which is great! These women are way less tolerant of sexist, disrespectful behaviour than the women of my generation. We still tried to negotiate our way around these things but the women today will have none of that, and it is really heartening to see that. I, thankfully, have been always vocal about my politics so people have not messed around with me too much but there are men who will constantly keep testing waters and see how far they can push things before they go out of control. Because roles within film sets are so deeply hierarchical, people still end up calling the Director, “Sir” irrespective of whether you’re a man or a woman. It’s just a deeply ingrained mindset that someone at the helm of things, has to be a man. Sometimes, my cameraman will say something and then I will say something but people on the set will still just keep looking at him. They’re just not used to having women around, calling shots.

Have you ever been called “bossy”?

Oh a woman will always be called “bossy” but a man will always be a “hard task master” or a “visionary.” I’ve been called “finicky” but then it’s my vision and my story and I will do everything in my power to ensure that it’s told in the most perfect way possible. It’s funny how everyone else thinks I am a perfectionist but in my head, I am compromising all the time!

Comments

0 comment