views

You've probably heard about Mitticool, the clay refrigerator from Gujarat, and Revolo, the plug-in system from KPIT Cummins that gives the benefits of a hybrid car. It’s likely you’ve learnt that Embrace, the infant warmer that originated from Stanford’s class of Entrepreneurial Design for Extreme Affordability, is now sold in India and elsewhere for one hundredth of the cost of incubators sold in Western markets. It’s also likely that you may have ranked these as low-cost solutions that smack more of improvisation than patent-toting innovation that modern businesses have built their edifices on.

In that case, you’re probably missing the point that the authors of Jugaad Innovation are making through a raft of well-executed ideas, from Brazil to China, from Argentina to India.

As the era of scarcity, of economic and natural resources, is upon us, the old structured way of innovation needs to be propped up by a new flexible, frugal model. In comparing and contrasting the Western and Eastern approaches to innovation, what was clear to the authors—Navi Radjou, Jaideep Prabhu and Simone Ahuja—was that the former was showing signs of strain and the latter had something going right for it, though not quite perfectly.

“We played around with the word ‘indovation’ for a while but it seemed more like an output of an approach as opposed to the mechanism,” says Radjou, who, as a consultant, had noticed that at the senior management level there was sensitivity about the shift in innovation and economic growth in the market place, though nobody was labelling it yet.

The authors coming from three different professional backgrounds—consultancy, academics and ethnography—decided to call it Jugaad and formalised the processes and principles in their book. If you’re familiar with the frugal, follow-the-heart entrepreneurship that grassroots entrepreneurs often epitomise, you may call the formalised version Jugaad 2.0. Its principles are: Frugality, flexibility, and inclusiveness.

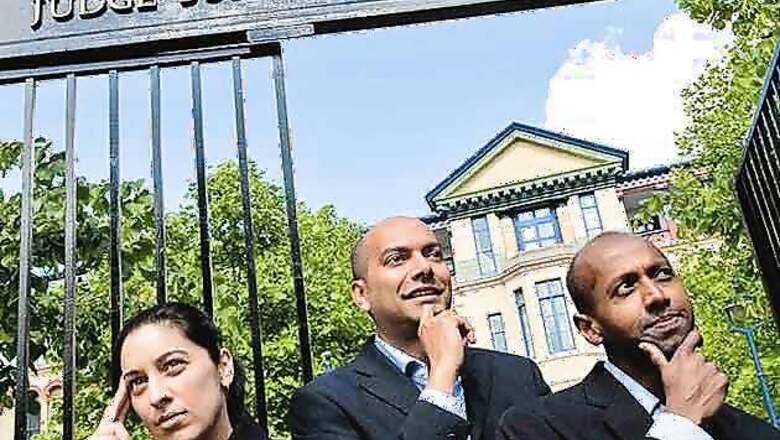

Tata Nano, according to the authors, exemplifies these principles. Yes, despite the cases of flaming cars and tepid sales. “Applying these principles at scale is not easy and that’s why Nano is a good example. Today, Tata Motors is saying that Nano 1.0 was not very successful, but we can apply the learning to Nano 2.0,” says Prabhu. As an academic at Judge Business School at Cambridge University, UK, he has watched structured innovation systems fail to respond to volatility caused by globalisation; how it misses out on the ingenuity that lies in the rest of the organisation, and even outside of it.

In practice, it’s not easy because Jugaad 2.0 is not about products, but about mindset. Some companies and executives are giving it a serious shot. PepsiCo chief executive Indra Nooyi has done something bold. At the company’s Gurgaon centre, she has created new metrics and benchmarks for cost efficiency globally and is asking, ‘If emerging markets can do more with less, can other centres do this as well?’ If she seems to be struggling with it, it is because turning a ship around that fast is hard; this is a long-term game, says Radjou.

Danone, having tasted the benefits of frugality in running a micro dairy product facility in Bangladesh, is seeking similar reduction in operating costs elsewhere without compromising on quality.

The authors believe these principles are, and will be, followed by two categories of companies: Multinationals like GE, 3M, Philips, GM, etc which are in India and are innovating here, not in terms of ‘reverse innovation’ but acquiring the mindset of frugality and flexibility and taking it back to their global centres.

Then there are Indian companies which are going global and can take these best practices to other locations. They are applying them in the local context. That is, communicate the philosophy of Jugaad and let the local managers implement them. By not ‘scaling’ them, they are avoiding the mistakes that multinationals made in going global, says Radjou. The next battleground, according to him, is going to be among MNCs who’ll have to unlearn some of the top-down mechanisms and try to espouse this new bottom-up approach. Indian companies in this regard have a clean slate as they don’t have to unlearn anything, he believes.

But one could argue why only MNCs, even some of the large Indian IT services companies that have industrialised their business processes need to unlearn the structured approach. The pendulum, which has swung too far towards processes, needs to swing back to people-centric approach, which is what IT service essentially is.

What is central here is the belief of the top management in these principles so that they enable their employees to fail, says Simone Ahuja. She says it with a lot of conviction. While producing her recent television series Indique—Big Ideas from Emerging India, her team lost a set of files containing expensive graphics. The US research and production team threw up their hands, whereas the Indian team managed to restore 90 percent of it. “It was not perfect, but a good solution that worked, without any extra cost.”

That was Jugaad for Ahuja. And it’s apparent the trio will revisit the subject soon. Businesses and governments are already seeking metrics by which to measure Jugaad.

Comments

0 comment