views

Writing Close Third-Person

Choose a character to follow. As the writer, pick which character you want the reader to experience the most intimately. This can be the main protagonist or someone very close to them. Try to pick a character you think the readers will latch onto. If you have a few characters in mind for your piece, create character breakdowns beforehand and see which one stands out to you the most. To help yourself choose, ask yourself the following questions:Do they have an interesting and unique perspective on the world?Do they have keen insight on certain topics relevant to the story?Am I going to enjoy spending a lot of time letting their thoughts and feelings inspire me?

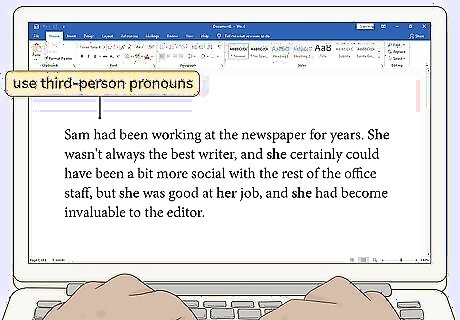

Use third-person pronouns and avoid using first-person pronouns. Use only “he/she/they” when referring to your character in the text. This is what makes it third-person instead of first-person, which uses pronouns like “I/me/we.” Using first-person pronouns all of the sudden will break the POV-wall (point of view) and throw off your readers. POV must be consistent because it’s the angle from which your readers are getting the story. A benefit of third-person is that it gives the reader a little breathing room from the character and allows you, the author, space and flexibility to move to and from different settings.

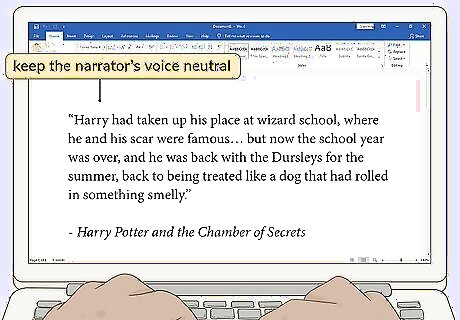

Keep the narrator’s voice small and neutral. Let your characters’ opinions and thoughts shine through the text, not those of your narrator. Think of the narrator as a reporter, not a commentator. The narrative voice should feel like a ghostly intermediary guiding the reader through the events of the story, not imposing any will on them. A good guideline is to let the narrator set the scene and then zoom in on the viewpoint character, reporting what they’re seeing and letting their thoughts inform the text. From there, the narrator is almost like a camera perched on their shoulder. On occasion, the camera can then sneak in through their ear to see from the character’s eyes. J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets and Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code are good examples of how the narrator can be colored by the thoughts and personality of the main character while still remaining a neutral reporter. If you like to write more in-your-face narration, consider writing in the third-person omniscient point of view instead. That way, your narrator is almost like a character themselves, telling the story from outside of the story and imparting their own thoughts and opinions. Note that the narrator isn’t the same as the character and has the license to reveal things the character themselves wouldn’t ordinarily confess (like a bad habit, for instance).

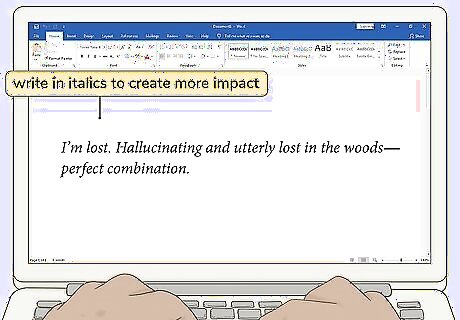

Convey direct thoughts of the character in italics. If you want your reader to see important thoughts directly from your character's mind, try using italics to set these lines apart. Think of it as taking away the tags "he/she/they thought" and letting the character speak for themselves. It's okay to use first-person pronouns in this case. For instance: Third-person (limited): "‘I am lost,’ she thought. ‘Hallucinating and utterly lost in the woods— perfect combination,’ she said to herself." Close third-person: "I’m lost. Hallucinating and utterly lost in the woods—perfect combination." For some inspiration, Robert Langdon, of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, often thinks in italics.

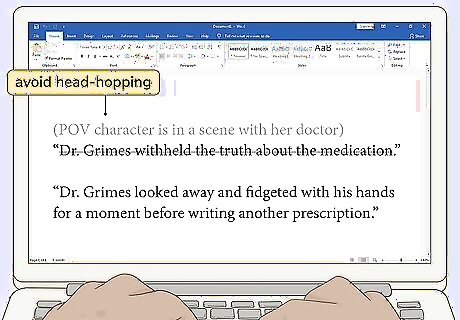

Don’t hop from person to person within the same scene. Within the same scene, chapter, or section, don’t hop from one character’s head to the next because it will confuse your reader. As an example, if the protagonist (the narrator, in this case) is in a scene with her doctor, you wouldn’t write “Dr. Grimes withheld the truth about the medication” because there’s no way your main character would know that. Instead, you can show things that might hint at that. For instance: “Dr. Grimes looked away and fidgeted with his hands for a moment before writing another prescription.” If you decide to switch characters, think about which ones are the right ones to inform your story because not every character’s perspective is useful to drive the narrative along. Only switch to a different character in a new chapter or after a section break. You might use the characters’ names as title chapters so your readers aren’t thrown off. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novel Love in the Time of Cholera is a great example of following different characters from chapter to chapter using third-person limited.

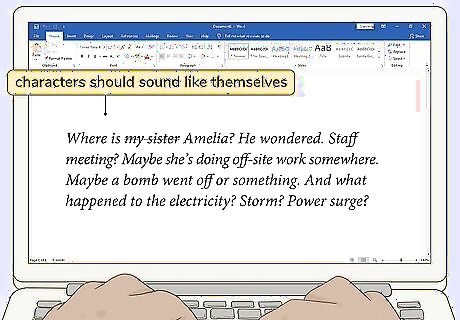

Omit words and sayings the character wouldn't use. Leave out signifiers that don't sound like something your character would actually say. This is where close third-person can get a little tricky, so go through each word as you're editing and make sure it fits with your character's personality, voice, and overall state-of-mind. For instance, writing "his sister Amelia" is problematic because your character probably wouldn't call his sister "sister Amelia." If your character would never use slang terms, don’t use them in the narration either.

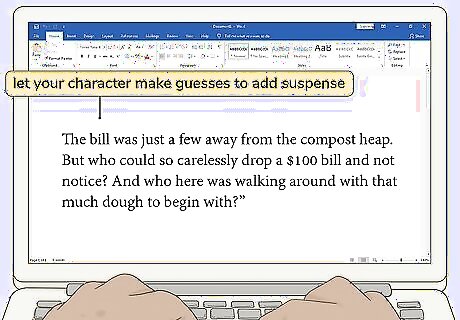

Let your character make guesses to add a sense of suspense or mystery. Since your character is discovering the world along with you, the narrator, consider including things they predict might happen. This can provoke a sense of commeraderie between your reader and the character. For instance, “The bill was just a few steps away from the compost heap. But who could so carelessly drop a $100 bill and not notice? And who here was walking around with that much dough to begin with?” This can instill your readers with a sense of doubt, wondering if the narrator is to be trusted or not.

Strengthening Your Prose

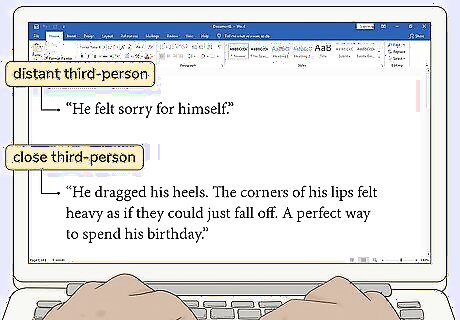

Develop your main character's voice. The voice and overall tone of the story are what hook the reader, so make sure the character you're following has a strong voice. Allow yourself to naturally enter the character's state of mind and discover what they may be thinking or feeling. It helps to distinguish between distant and close-third person here—think like a film director to help you zoom in on the character’s internal state. For example: Distant third-person: "He felt sorry for himself." Close third-person: "He dragged his heels. The corners of his lips felt heavy as if they could just fall off. A perfect way to spend his birthday." Both distant and close third-person can fall under the categories of limited or omniscient POV. The difference is where the narrative “camera” is placed—if it’s across the room, that’s distant third-person. If it’s zoomed in tight or on the character’s shoulder, that’s close third-person.

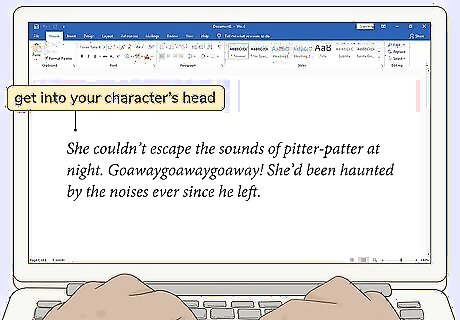

Get into your character’s head to figure out their thoughts and feelings. Write a sketch in first-person to see how you think the character might be feeling in a particular circumstance. It’s okay to use first-person pronouns (I, me, we) for that exercise, but drop them when it comes time to work the content into your prose. This is where close third-person verges on feeling like first-person, but you use only third-person pronouns (he, she, they). For example: First-person sketch exercise: “I couldn’t escape the sounds of the pitter-patter at night. Goawaygoawaygoaway! I’d been haunted by the noises ever since he left." Close third-person: "She couldn't escape the sounds of pitter-patter at night. Goawaygoawaygoaway! She’d been haunted by the noises ever since he left."

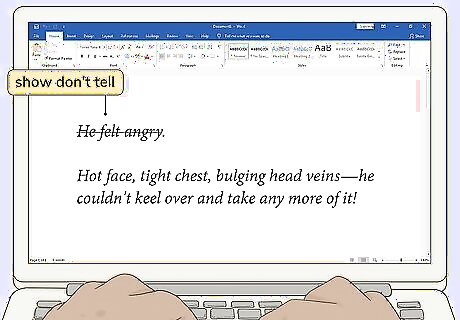

Show your readers what's happening instead of telling them. Don’t filter the action. Instead of saying something like: "He felt angry," show your reader what that anger looks like. For instance: "Hot face, tight chest, bulging head veins—he couldn't keel over and take any more of it!" Showing (instead of telling) allows your readers to paint a picture in their heads as they're reading. This is key to breathe life into your words and keep them turning the page. Avoid using "telling" verbs like: saw, observed, noticed, tasted, felt, heard, smelled, and thought.

Be open to changing your plans for the plot as you’re writing. Sometimes you might get so close to a character during the writing process that your plans about the plot might seem less of a good fit. While you’re writing, tune into your characters’ motivations and feelings to see what feels right for them. You can steer them in a certain way, but don’t let your plans trump an idea that comes naturally to you while you’re in the mindset of a character. For example, you might discover that your broken-hearted heroine would never stalk her ex-lover to the extent that you’d originally thought up for the sake of an ultra-dramatic run-in. Instead, she might be more of a desperate romantic, leaving him ornate love letters on his doorstep every day. Discovering new things about your characters and the world they live in is part of the joy of writing—go with it and see what happens!

Comments

0 comment