views

Writing a Good Melody

Learn to play other songs first. If you want to write a book, you've got to read a lot of books first. Listening to music and learning to play it is the first step in learning to write a song, especially a good song. Learn to appreciate the wit and structure of a well-written song. If you want to be a good songwriter, be a good listener. Check out some of the masters: Classic pop: Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller, Irving Berlin, Yip Harburg Pop-Rock: Randy Newman, Paul McCartney, Carole King, Brian Wilson Contemporary Pop and R&B: Michael Jackson, Max Martin, Linda Perry, Timbaland, Pharrell Williams Country and folk: Townes Van Zandt, Lucinda Williams, Kacey Musgraves, Hank Williams

Pick an instrument to compose on. Unless you're Mozart, it's tough to write a good song in your head, or just on paper. Most songwriters have a specific instrument they like to compose on, to hear the music as it is played. Most pop songs are written on piano and guitar, while other types of music are commonly composed on other stringed instruments or horns. You can write a song on any instrument. If you can't play an instrument, check out other articles to learn more about picking an instrument and learning to play.

Play around with chords until you find something you like. Choose a key signature, and find the related chords in that key. Then, play around with the order of the chords to find something you like. Stick to a major key if you want to write a memorable song. Of the ten most popular songs of all time, only one is in a minor key. Lots of songs are written with the I-IV-V chords, which means the chord based on the first, fourth, and fifth note in the scale. So, in the key of C, the chords C, F, and G all sound good together. This is true of any key. Learning the basic scales for the major keys in your instrument is really helpful in learning to write songs. Learning to read music can help you be a better songwriter, but it's not absolutely necessary. Simple pop songs are often written by untrained performers.

Explore other notes in the scale to find a melody. Melodies won't be an exact copy of the chords in the scales, but will be based on those chords. Pick around the notes of each chord as you play to find a good melody, and explore the notes outside the chords but in the scale, as well. To find a melody, lots of people like to hum along to the chords, or sing nonsense syllables or words to go along with the melody. Hum or whistle while you play, before there are lyrics.

Make it as simple as possible, but with a twist. Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind," Hank Williams' "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry," and "Gotta Give it Up" by Marvin Gaye are all made of four chords or less. Most good songs are relatively simple, with a little quirk added to make it memorable. If you want to write a great song, it doesn't need to have five key signatures and fifteen time signatures thrown into the mix. Keep it as simple as possible. Listen to John Lee Hooker play "Boogie Chillun'" and try to work out the chords. Give up? There's only one. The song is iconic because of the weird timing and rhythm, not the complexity of the melody or chords. Listen to Marvin Gaye's "Got to Give It Up" and compare it to a simple 12-bar blues song. See how the switch up to the IV and V chords is delayed a few bars? That's the kind of twist we're talking about.

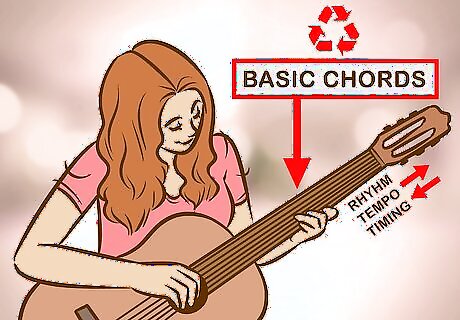

Borrow a basic chord progression and change it. When you're first starting out, learn lots of different songs and borrow the basic chord structures, but play them at a different rhythm, different tempo, and with different timing. Write different melodies to the basic chords. This isn't plagiarism, it's songwriting. Learn a chord progression and then play it backwards and write a new melody. "Whole Lotta Love" backwards could be your new opus. Take all the chords from your favorite song and just play them in a different order until you find something you like. Lots of songs sound like other songs. It's not a bad thing. As long as you're not doing a straight-up copy of the rhythm and timing and melody all together, you're still writing a new song.

Writing Good Lyrics

Find a subject that matches the melody. When you've got a basic melody that you like, keep playing it to yourself and letting your mind wander. What kind of mood does the melody have? What does the song remind you of? Start brainstorming possible lyric topics. If you've written a whimsical or melancholy song, start thinking of images. What does the song remind you of? Who does it remind you of? What do you picture when you think of the song? Just start brainstorming on paper. Think of stories, think of characters, think of places, think of moods. Start writing little fragments and lines that illustrate those ideas. Alternatively, find a subject that complements the melody in a strange or interesting way. Warren Zevon's "Excitable Boy" sounds like an upbeat piano ballad, even though the lyrics are about a deranged serial killer.

Write a few lines. Once you've got your theme or subject in mind, write out a few lines that you think are good to start building around. You can start with a chorus line that makes the theme or subject obvious, or just start writing the verses and find the chorus later. Think of a powerful image or detail to start with: "Pistol shots rang out" starts Bob Dylan's "Hurricane," about a man falsely accused of murder." Or the iconic start to "Long Black Veil": "Ten years ago on a cold dark night / Someone was killed beneath the town hall light." It's also fine to just start sketching and free associating words. Because you'll eventually pair this with a melody, good lyrics don't have to make a whole lot of sense: "Wounded lover, got no time on hand / One last cycle, thrill freak Uncle Sam" as the Rolling Stones put it.

Find a chorus to repeat. There are lots of different ways to approach the chorus and make it fit the song, but usually you want the chorus to be the part where the theme or the subject is summed up in a tidy little phrase or sentence that sounds good to the ear. You might try writing for a while around a couple verses, then pick one that stands out to you as being the best to repeat, or try to write a chorus separately. Here are some good ones: "A few good federales say they could have had him any day / They only let him slip away out of kindness, I suppose" from "Pancho and Lefty" by Townes Van Zandt "How does it feel to be on your own / With no direction home / Like a complete unknown / Like a rolling stone" from "Like a Rolling Stone" by Bob Dylan "Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be / Whisper words of wisdom, let it be" from "Let it Be" by the Beatles "Go, Johnny go! Go, Johnny go! Go, Johnny, go, go, go / Johnny B. Goode" from "Johnny B. Goode" by Chuck Berry

Use a variety of rhymes. The hardest part about writing a good song is finding the right lyrics to match up with it. Most song lyrics include rhyming end words, but all songs don't have to rhyme. Learn a little about how to rhyme properly to get your song lyrics to match up with the music. Most lyrics aren't formally structured into a rhyme scheme, but it depends on the song. An ABAB rhyme-scheme might be perfect for the song you wrote. Avoid cliches. Just because words rhyme doesn't make them good for your song. If the rhymes seem obvious ("I love my baby / I don't mean maybe") it's best to look for something else.

Make lyrics specific. Many beginner lyricists write lyrics full of abstract ideas and not specific images. Give us something to see, don't tell us things. Avoid big concepts like "time" or "love" or "depression" in your lyrics, as well as mixed metaphors. If you're writing, "The bleak rage of my depression / Time is like a lesson" then try to make your lyrics more specific. If you tend to write in abstractions, write out your big abstracts and describe what specifically they make you think of. What does the "bleak rage of your depression" look like? Sitting alone at three am, drinking coffee? Stabbing out a cigarette into an ashtray already overfull? That's better.

Keep it simple. Use as few words as possible in your lyrics. Make them count. Unlike a poem, you don't have to fill your lines to the brim, because you'll have the addition of music. Use as simple a structure as possible in your lyric-writing. Look at the lyrics to a song you really like. Without the song, they probably won't look that great, but they'll probably be simple and specific. Do the same with your song. Keep revising words away from your lines as you try to sing them. If something gets stuck in the mouth, figure out a way to sing the song without it.

Consider writing with a partner. Lots of songs are written in pairs. Jagger-Richards. Lennon-McCartney. Leiber-Stoller. If you've got a handle on the music-end of things, consider enlisting a lyric-writing partner to help give you a new perspective. If you're a better lyricist, hook up with someone who's a whiz with melodies. Lots of performers, from Elton John to Elvis, didn't actually write most of their own material on their own. Writing with a partner is a long-proven effective technique.

Putting it All Together

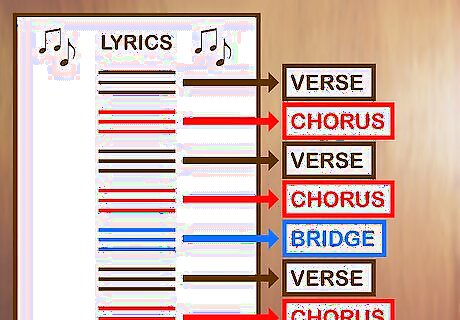

Structure the verses and the choruses. Songs can be structured in lots of different ways. A basic song-structure, though, will consist primarily of alternating verses and choruses. The verses will usually change, while the chorus generally remains constant in most songs. Choruses are usually the "hook" of the song. What's the part of the song that gets stuck in your head? What's memorable? That's the chorus. Repeat it at least three times to make the song memorable. A verse will usually, but not always, start the song. This allows you to build up to the chorus, which is usually the most catchy or memorable part of the song. Some songs have no chorus at all. Lots of rap songs, for example, are just flow. Some songs, like Bob Dylan's "Desolation Row" are just long verses, which all end on the same phrase, though there's not a typical chorus.

Consider including a bridge or a breakdown. Bridges are a one-time variation of the chorus structure in the song, which happens about three-fourths of the way through the song, between a chorus and a verse, or between two choruses. It's just a way of shaking up the song. In some kinds of music, like metal songs and high-energy dance songs, a breakdown is more appropriate than a bridge. This usually involves cutting everything but the drums and some vocals for a few bars, to get people moving. Often, bridges involve a switch into the minor key for a few bars.

Sing the song to work out the phrasing. Just because you've got a melody and rhyming words doesn't mean you've got a song yet. Learning to fine-tune the song by working out the phrasing is essential to writing a good song. Keep working on your song, singing it to yourself repeatedly, to learn how the melody can be adjusted in the voice, and how the lyrics can be tweaked. Even if you're not a great singer, it's important to sing the song as the songwriter. Find a place where nobody will hear you, if you're sheepish about your voice. Belt it like Beyonce.

Perform the song for an audience. Songs are meant to be heard. It can be very helpful for aspiring songwriters to get feedback on their material, especially from other songwriters or musicians who appreciate music. Playing a song for your family or close friends who aren't music listeners will usually not be that helpful. They'll usually just say, "I love it! Great job!" That can be good to hear, but if you want to write a great song, seek out songwriters for feedback. Record it and listen back to it yourself, if you're too embarrassed to play your song for someone yet. Listen to how it sounds. What could be better?

Keep revising the song. Bob Dylan claims to have written "Blowin' in the Wind" in fifteen minutes, while Leonard Cohen claims to have never been fully satisfied with "Famous Blue Raincoat," even though the song is 40 years old. Don't stop working on a song. Keep hammering out the little details until it comes into shape. If you want a song to be good, it's not enough to be able to sing it.

Comments

0 comment