views

Researching for Your Debate

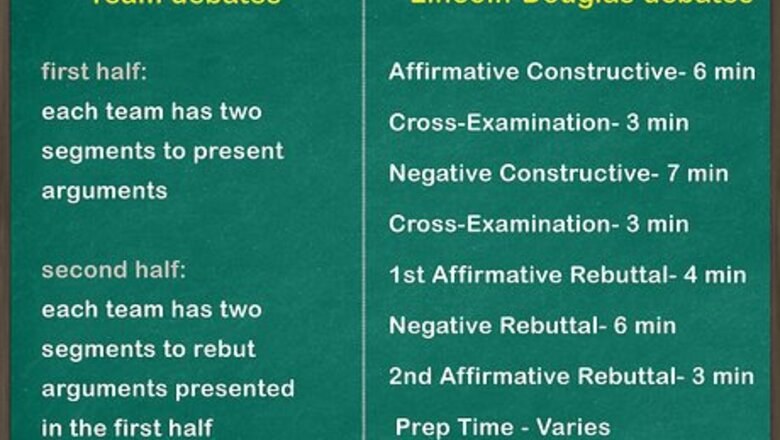

Identify the form of debate your outline is for. There are several different types of debate, such as parliamentary debates and Lincoln-Douglas debates, that each have their own organizational structure. The order in which speakers present their arguments differs between each debate form. Thus, you'll have to base your debate outline on the particular structure of the debate you'll be engaging in. Team debates are one of the most common debate forms. In the first half of the debate, each team has two segments to present arguments for their side. In the second half of the debate, each team has two segments to rebut arguments presented in the first half. Lincoln-Douglas debates are set up to allow one side to present their arguments, and then the other team to cross-examine them. The second team then presents their arguments and has the first team cross-examine them. Finally, each team has an opportunity for a final rebuttal.

Research the debate question and decide which side to take. Use quality sources, such as peer-reviewed journals and academic books, to gather the best information possible about your debate topic. Focus on finding relevant facts, statistics, quotations, cases, and examples that are related to the topic at hand. Then, based on this evidence, decide which side of the debate has the strongest argument and take that side, if possible. For example, if the topic of the debate is on the environmental impact of gas cars versus electric cars, gather research from academic journals and consumer watchdogs on carbon emissions, what impact carbon has on environmental degradation, and statements from experts on the topic, such as environmental scientists and car manufacturers. If you're writing the debate outline for an assignment and can't pick your own side, focus on gathering as much evidence as possible to strengthen the argument you're tasked with making. Whatever argument you ultimately make, make sure that it is logically sound and that you have convincing, relevant evidence that supports it. Be sure to note all bibliographical information on your notes. For every supporting piece of evidence you find for your case, try to find another piece of evidence to counter it. This will help you build your argument later. It is better to include more points than you think you will need, than not doing enough research and lacking evidence.

Categorize all the evidence you come across in your research. On a piece of paper, list all the different pieces of evidence you've found that supports your case (the primary argument you're making). Order it so that the most influential and powerful evidence is the first to be presented, mediocre evidence is in the middle, and a final powerful piece is at the end. Then, make the same kind of list for all the evidence you've found that supports your opponent's argument. For instance, if your most compelling piece of evidence is a graph that shows that gas cars emit twice as much carbon as electric cars, place this at the top of your evidence list. If you have a fairly lengthy debate planned, break up your case evidence into categorical sections. For example, you could have legal, moral, and economic support for your case. Aim to have a minimum of 3 supporting facts or pieces of evidence in your case outline.

Creating the Basic Outline

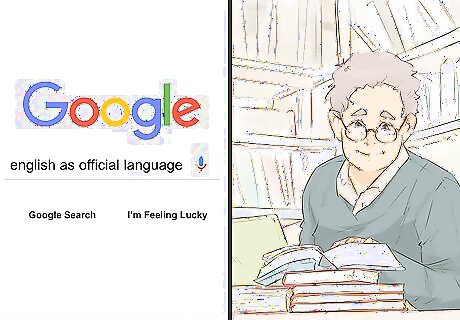

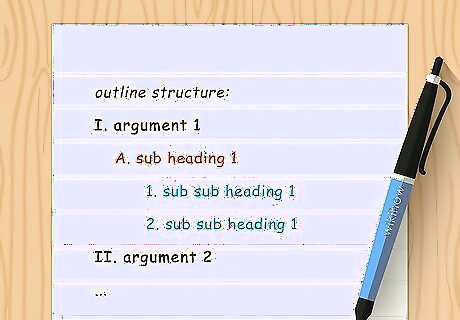

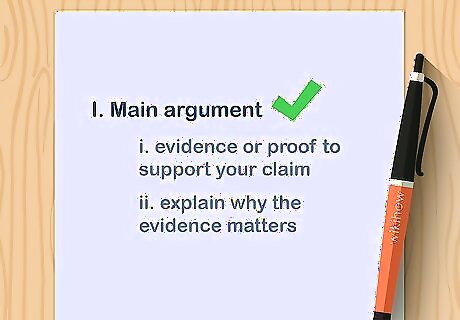

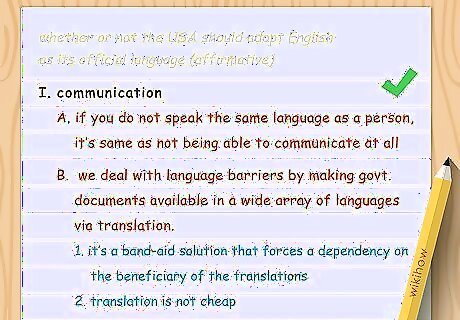

Follow outlining principles that will keep your outline organized. While the order of your material will be determined by your debate form, the format for your debate outline should follow the basic guidelines for outlining. Organize your outline with main headings and subheadings marked by Roman numerals, capital letters, and Arabic numerals. Subdivide information. Main headings will probably consist of arguments, while subheadings will contain different pieces of supporting evidence. Use correct symbols. Each level of the outline has a particular symbol to use. The main headings will use Roman numerals (I, II, III, IV). Subheadings use capital letters (A, B, C). Sub-sub headings use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3). Keep these consistent throughout your outline. Indent each level. Indentation helps you follow the line of argument and keeps your outline organized.

Start by outlining your introduction. The introduction should include an overview of the research question or topic of debate, as well as a thesis statement for your overall argument. On a sheet of paper, write a bullet point with the word “Introduction.” Then, write an indented bullet point below this summarizing the debate topic. Finally, write another bullet point below this one that states your thesis. Your thesis statement should explain which side of the debate you'll be taking and why your case is stronger than your opponent's. For example, if you're debating whether gas cars or electric cars are cleaner, your thesis statement might be: “Electric cars are cleaner than gas cars.”

Write out your first main point in the form of a thesis statement. Create a second main heading marked as “Arguments” and write out your principal sub-argument as the first subheading in this new section. This line of argument should be the most convincing piece of evidence for why your overall argument is correct. For example, if you're arguing that electric cars are cleaner than gas cars because they produce less carbon dioxide, your first main point would be: “Electric cars produce less carbon dioxide emissions than gas cars.”

State the relevant evidence and significance for this main point. Add additional subheadings below your first line of argument and briefly write out all the relevant pieces of evidence that support this claim. Then, add a final subheading and explain why this sub argument is important to the overall case you're making in the debate. For example, the evidence that electric cars produce less carbon dioxide emissions than gas cars might include statistical information compiled by the Energy Department and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Repeat this process for each additional part of your argument. Create a subheading for each line of argument you'll make to advance your overall argument. Then, write out the evidence and significance for each of these sub-arguments as well.

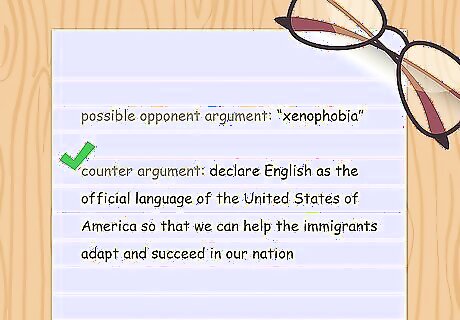

Prepare rebuttals to address potential counterarguments. You will have the opportunity to rebut or question the arguments presented by the other side. Identify potential arguments they may bring up. Many opposing arguments will probably be addressed in your research. Brainstorm different ways to counter these arguments during your rebuttal should the opposing side bring it up. For example, if you're pretty confident that your opponent will argue that your evidence relies on biased sources, you can prepare a rebuttal to that claim by finding additional evidence to support your argument from a variety of sources. Look to find rebuttals for both the individual parts of their argument in addition to the whole of it. This will fortify your position in the debate. Many times their argument will be the opposite of yours, so while your argument lists the pros, theirs is listing the cons of a particular value. If you pay attention to this, you will be able to not only prove their side of the argument invalid, but also help to further promote your own.

Add detail to your outline. When you have made a bare bones outline of your case and rebuttals, begin adding a bit more detail that will benefit either essay writing or debating on the subject. Keep the outline form of headers, sections, and bulleted lists, but write in complete sentences, add in helpful questions and evidence, and make your argument more well rounded than just a list of a few words. Write this more detailed outline as if you were actually speaking in the debate. This will help you to better understand your own argument and come up with logical questions and rebuttals for your opponent.

Avoiding Logical Fallacies

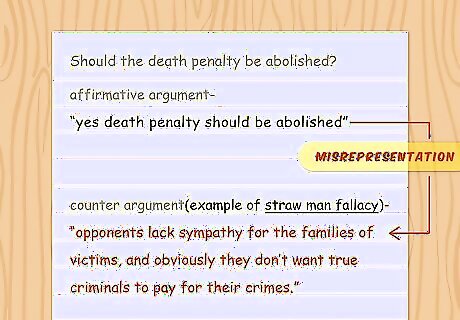

Steer clear of using a straw man argument. Often used by beginning debaters in their outlines, the straw man fallacy is when you misrepresent your opponents case by describing it wrongly to the audience. Make sure you don't do this in your rebuttal and be ready to call out your opponent if they do it to you. For example, if you're promoting the abolition of the death penalty, your opponent might commit the straw man by accusing you of lacking sympathy for the families of victims, and that you don't want true criminals to pay for their crimes.

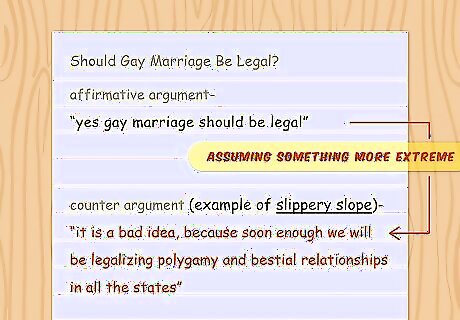

Refrain from making assumptions to dodge the slippery slope fallacy. This happens when you assume something more extreme will happen on the basis that something less extreme is about to occur. Although this sounds intuitive, it actually isn't a logical line of argument and should be avoided. For example, if you're arguing for legalizing gay marriage and your opponent says that it is a bad idea, because soon enough we will be legalizing polygamy and bestial relationships in all the states.

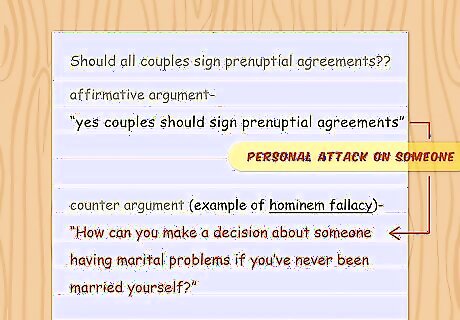

Avoid the ad hominem fallacy by not attacking your opponent. Often used by the losing part of a debate, the ad hominem fallacy is when instead of attacking the merit of a case being presented, the opponent makes personal attacks against the person presenting the case. This is both illogical and unbecoming, so you should especially avoid this fallacy in a formal setting. For example, if you've presented a well-crafted argument for your case but your opponent has not, they may instead try to call out your bad grades as a rebuttal. Even if this is true, it isn't relevant to the topic of the debate and therefore isn't logically valid. Even if your opponent brings personal issues and insults into a debate, you should never do this back to them. Not only is it logically fallacious; it's also widely considered rude.

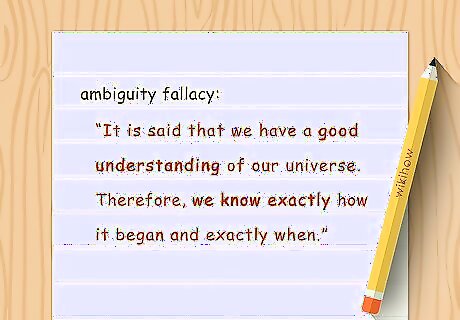

Stick to using specific language to avoid the ambiguity fallacy. Using ambiguous or all-encompassing language can make your explanations and descriptions vague or unclear. This not only makes it easier for your opponent to potentially hurt your case, but also makes it seem like you don't quite know what you're talking about. For example, if you were to claim that electric cars are “always” cleaner than gas cars, your opponent might point out that a gas car in a carwash is cleaner than an electric car covered in mud. To avoid this fallacy, steer clear of ambiguous words like “always.”

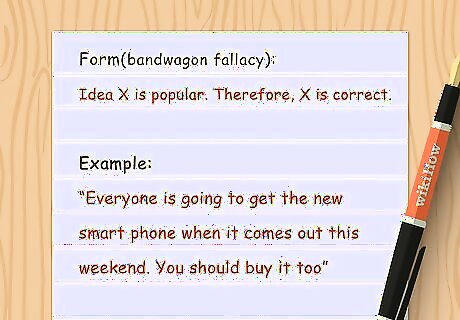

Stay away from the bandwagon fallacy. This is one of the most commonly committed fallacies, in which you assume something is correct or good simply because it is of popular belief. This fallacy is also known as “appeal to the populous.” For example, it would be logically fallacious to argue that the death penalty is the most effective form of punishment just because most people support it.

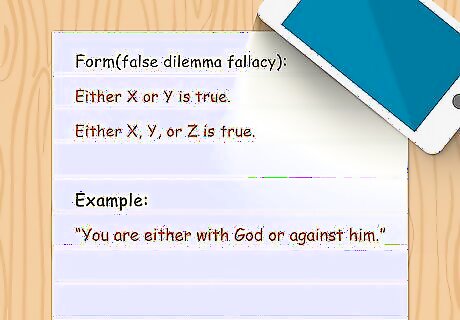

Be careful of using the false dilemma fallacy. Often used at the end of a debate to highlight the goodness of making a decision in your favor, the false dilemma fallacy occurs when you offer only two final options (black or white) when there may indeed be several other options available. If you engage in this fallacy and your opponent points out a third final option, your argument will look very weak by comparison. For example, your opponent states that as a result, the only two options are to legalize all drugs or to outlaw them.

Comments

0 comment