views

Getting Help

Ensure that your child is properly examined in the hospital. Depending on the details surrounding your child's suicide attempt, they may have been admitted into the emergency room or hospital for acute care. In some states, a mandatory overnight or three-day stay is required for suicidal patients. The primary focus at first is in stabilizing your child's medical condition. After that occurs, a full psychiatric evaluation is performed and your child is closely observed for reattempt. The evaluation is geared towards: Determining your child's medical history (i.e. any medical conditions, medications, history of substance use, head injuries, etc.) Performing a mental status exam Getting labs ordered (i.e. toxicology screenings, blood glucose, complete blood count, etc.) Assessing your child for common mental disorders that accompany suicide attempts, such as depression or alcohol abuse Evaluating their support system Evaluating their coping resources Assessing for the likelihood of a second attempt

Set your child up for outpatient therapy and medication management. Know that, after this first attempt, your child is at an increased risk of later dying by suicide. As many as 20% of those who attempt go on to complete a suicide. To give your child the best chances, have a plan for moving forward before releasing them from the hospital. Be certain that you have a referral or appointment scheduled for an outpatient psychologist, psychiatrist, or counselor. Make sure you have any prescriptions in hand so that you can get them filled as soon as possible.

Develop a safety plan. Ensure that both your child and your family is equipped with the knowledge and resources to identify suicidal ideation and get help in the future. Your child's medical provider should sit down and have your child complete a paper form safety plan. This form outlines coping strategies your child can apply on their own when they feel suicidal, such as exercising, praying, listening to music, or journal writing. The plan also lists your child's support network like friends, family members, and spiritual advisors that your child can reach out to for help. In addition, contact numbers for mental health providers and suicide hotlines are provided. The plan will also discuss what means your child has for dying by suicide and ways they can reduce their access to these potential weapons. Your child will be asked about the likelihood of following the safety plan and the importance of compliance will be emphasized.

Beware of the warning signs. Your child's safety plan is useless unless they and you know and understand the warning signs for suicide. Your child may or may not be able to talk about their thoughts or examine their behaviors, and therefore may be unable to implement or access resources of the safety plan. As their parent or caregiver, it's your responsibility to examine and observe the behaviors of your at-risk child. The warning signs may include, but are not limited to: depression or particularly low mood for an extended period of time loss of interest in normally pleasurable activities feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or hopelessness remarkable change in personality substance use withdrawal from family, friends, and regular activities giving away possessions talking or writing about death or suicide decline in performance in school or work

Join support groups. As your child regularly reviews their safety plan and attends outpatient or group psychotherapy, it may also be helpful to participate in a local support group for suicide attempt survivors. Such a group may help your child to forge connections with others who have endured a similar journey, help them to assimilate their mental disorder or suicide attempt into their self-concept or identity, and give them support to cope with suicidal ideation or depression. Support groups are also available to guide families through the difficult time of coping with a loved one who has attempted suicide.

Consider family therapy. Family conflict, abuse, and communication blocks may contribute to adolescent suicidal ideation. Most traditional treatment methods are directed at helping the adolescent develop coping strategies and problem-solving skills. However, research has shown that the influence of family can be integral to reduced depressive and suicidal symptoms in adolescents. One type of family therapy, called Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT), has been proven to be effective in improving the functioning and relationships of the family after a suicide attempt. This form of therapy strives to get adolescents and their families working together to problem-solve and increase communication. Adolescents are seen one-on-one to identify barriers in the family that prevent communication and develop skills to overcome those barriers. Then, parents are seen one-on-one to learn healthier parenting strategies and how to be more loving and supporting with the children. Finally, everyone meets together to build skills that improve functioning and communication. During this time it is important to work on your relationship with all of your children. The other siblings may be emotionally neglected after one child has attempted suicide. Some of these issues may be addressed in family therapy. Still, make an effort to talk to each of your children about how they are coping during this trying time.

Controlling Your Emotional Reaction

Manage your response in the days that follow. Your reaction after a child attempts suicide varies, but generally the reaction may be a mixed bag of difficult emotions. You might be intensely angry. You might be tempted to never let your child out of your sight again. You might feel guilty. Whatever you feel, keep these emotions in check around your child. Your child obviously needs you. Remember, the only way they knew how to deal with what they were feeling or experiencing was to take their own life. Immediately after, resist the urge to ask "why?" or assign blame. The details will eventually come out. The important thing right now is that your child is alive. You need to express love, concern, and appreciation that they are still here with you, that you have a second chance. Avoid reprimanding your child or teenager. This may only make the situation worse and perhaps even push them to make a second attempt. Use "I" statements and openly tell your child how scared and upset you were. Prompts for talking with your child may include: I feel terrible that you did not feel you could come to me with a problem. I am here now, though, so please tell me how you truly feel. That way, I can help you to feel better and be happier." I'm so sorry that I didn't know something was wrong. I want you to know that I love you and, no matter what, we will get through this as a family. I understand you must be hurting. Tell me how I can help you.

Attend to your emotional needs. Caring for a child who has attempted suicide can be an emotionally draining job. Remember, you can't give to anyone if your own cup is empty. Look after yourself, too. Panicking, punishing, blaming and criticizing will not help your child or your family. If you have the urge to do these things, take time away for yourself. Ask a friend or family member to supervise your child and get some alone time. Write down your thoughts. Pray. Meditate. Listen to relaxing music. Go for a walk. If you must, cry your eyes out.

Talk to someone for your own well-being. Enlist the help of close friends and relatives to help you and your family as you cope with the aftermath. Don't be afraid to ask for help when you need it. Lean on a supportive friend, family member or co-worker. Do not give in to the pervasive stigma about suicide and mental illness. Talking to someone else about what you and your family are going through can help you gain encouragement and come to terms with your feelings about the situation. Plus, sharing your story might help another person identify suicidal behavior in an adolescent, and maybe save a life. Be discerning about who you turn to for help. Find people who are supportive and encouraging—sometimes even trusted friends can be unexpectedly judgmental. If you are having difficulty coming to terms with what's happened, if you cannot control your anger or hurt feelings, or if you constantly blame yourself and your parenting skills for your child's suicide attempt, you should see a counselor. Reach out to a support group or one of your child's mental health providers for a referral to a professional who can help you sort through these feelings.

Prepare for upsetting information as it comes out. Having someone you can confide in or speaking with a mental health provider will be significant in the coming weeks. You can expect to learn some difficult information about your child and their health and well-being. Chances are, you'll come to understand some things that you missed before. Expect this and, regardless of your opinion, try to be supportive anyway. For example, your child may have tried to take their life because they are being bullied or as a result of sexual molestation or assault. Your child may also be struggling with their sexual identity or a drug or alcohol problem, which may also put them at a significantly higher risk for suicide. Be willing to own your part of what might have gone wrong or what you might have missed, and make an effort to change what you can.

Preventing Future Attempts

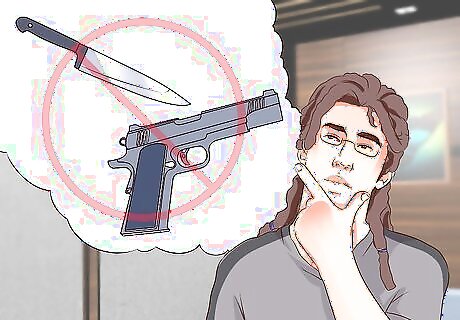

Remove any and all weapons. Before your child even comes home from the hospital, you should perform a thorough sweep of each bedroom, the bathroom, the kitchen, and any other rooms such as storage closets or garages for potential weapons. Your child will discuss means in the safety plan with their provider. Nonetheless, to minimize the possibility of reattempt, remove guns, knives, rope, sharp objects, and medications from the home. If medications must be kept in the home, keep them locked up or available in limited amounts.

Create a supportive environment at home. Talk to your entire family openly about suicide. Refrain from acting like it's a shameful secret that should be pushed under the rug. Emphasize that all of you will get through this by sticking together. Speak to each family member separately and either delegate tasks or ask what each person can do to help out during the current situation. For instance, an older sibling might volunteer to watch a younger sibling (not the attempt survivor who should be under adult supervision as much as possible) while the parents take the other sibling to therapy or support groups. Do what you can to minimize arguing and keep the emotional climate of the household calm and encouraging. Plan entertaining family activities like game nights or movie night to stimulate bonding.

Let your child know that they can talk to you. Remind your child of their importance in your life and in the family. When your child finally feels up to talking to you, listen without judgment. Avoid statements such as "You have nothing to be depressed about" or "Other people in the world have it worse off than you"; these are very invalidating and harmful. Do your best to hold on to the love and compassion you have for your child during this difficult time. Periodically check in with your child to monitor progress in treatment and to ask how they have been coping. These gentle and frequent check-ins may help you notice signs if your child's emotional state is deteriorating. In the younger years, kids tend to be "open books". However, once they are in elementary school, they start to become tight-lipped. Avoid asking close-ended questions if you want to get your child talking. Also, refrain from using "why" in a question as it can lead to them clamming up or becoming defensive. Instead, use open-ended questions that require a more lengthy answer beyond "yes" or "no". For example, "What was good about your day today?" is more likely to get your child to open up rather than "How was your day?", which could lead to a one-word response such as "fine" or "good" that is a conversation ender. It may also be a good idea to start a dialogue with your entire family. Get everyone comfortable talking about their day-to-day interactions at school or work. Doing so can make it easier for your children to discuss potential problem areas, which will aid immensely in preventing future suicide attempts.

Encourage your child to become active. Recovery after a suicide attempt can be a long, arduous process. When you notice your child exhibiting signs of depression or suicidal ideation, motivate them to get out and do some exercise. Physical activity can serve as a distraction from negative thought patterns. Plus, getting active provides your child with much-needed endorphins, which are feel-good chemicals produced in the body after exercise. These chemicals help alleviate stress, anxiety, and depression. New research shows that bullied students demonstrate a 23% decrease in suicidal ideation or attempts when they engage in physical activity at least four days per week.

Buy your child a journal. Journaling has a multitude of mental health benefits from relieving stress and lowering depression to helping the writer identify triggers and negative thought patterns. Talking about their problems - or writing them down on paper - can be cathartic and actually help reduce suicidal thoughts and symptoms.

Comments

0 comment