views

Yangon: In a ramshackle workshop behind a bustling Yangon market, Kyi Tha fixes the plastic propeller of a home-made drone, one of a growing number of enthusiasts refusing to let poverty clip the wings of their hi-tech dreams.

A new generation of creative young inventors have turned to the Internet to catch up with the rest of the world, after years of isolation under junta rule left the country with little access to engineering expertise or cutting-edge technology.

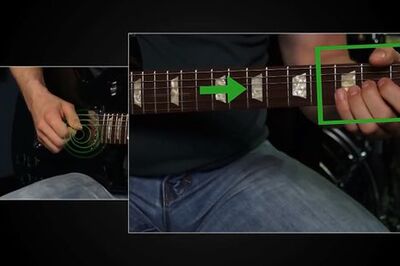

"Studying drone technology is not easy in Myanmar. So we watched videos about it on YouTube," said Kyi Tha, admitting he watch clips for months, patiently enduring notoriously slow web connections in his search for knowledge.

"First we did not have any success, but after experimenting for one year we could do many things," he told AFP.

Kyi Tha, 26, and his cousin Thet San, 30, have transformed a modest wooden home into the nerve-centre of their engineering and technology business, Myanmar Future Science.

A workbench in the backyard is cluttered with the signs of feverish invention -- boxes of screws, aluminium rods, and the body of a model aeroplane.

Their firm makes its money providing engineering services to the government and private firms, using drones and model aircraft to conduct aerial surveys for maps and assessments of agricultural areas.

But their passion is opening up the world of technology to fellow budding inventors. They have a little shop in their garden packed with tiny motors, propellers and plastic body-parts for drones, planes and radio-controlled cars.

Myanmar's youth are eager to keep up with the latest technological developments, but are often held back by poverty -- a legacy of decades under junta rule.

A new ready-made drone could set you back up to 300,000 kyats (around $230), far beyond the financial reach most young people in Myanmar, where the World Bank puts average annual income per capita at $1,270.

But enterprising gadget builders rely on creativity to keep their costs down to just $10 -- using materials like polystyrene foam packaging to build their models and seeking out cheap engine parts.

"This is our hobby. We are crazy about making things with these accessories, just as many young students in Myanmar would like to do," said Kyi Tha, who imports most of the parts from China.

Flying free

Drones are the tool of choice for legions of photographers and video-makers eager to capture a bird's eye view of everything from tourist attractions to protests.

Australia has begun using them to track sharks with the hope of protecting swimmers from attack, while Amazon wants to use them for shopping delivery. But their burgeoning popularity has also caused security jitters.

In September a drone crashed at the US Open, causing the match to be interrupted, the latest incident in America, which is considering mandatory registration.

In Southeast Asia some countries, like Cambodia, have imposed strict controls on drone use. But the nascent field remains largely unregulated -- for now.

Model aircraft are not currently subject to specific legal restrictions in Myanmar, although authorities are believed to be mulling regulation.

On weekends and holidays, teams of enthusiasts take their flying machines out for a spin in Yangon and the less populous industrial outskirts of the city.

As his new drone swooped through the air in a park near Yangon's revered Shwedagon Pagoda one local IT worker said most objections he normally receives are vague concerns over "security".

"I just want to show Myanmar's beautiful scenery in my drone footage," he told AFP, asking just to be referred to by his nickname, Ethan.

"People love drone shots, they're awesome. When my drone is flying I feel amazing, very happy," he said.

Sky's the limit

At the Myanmar Aerospace Engineering University in the central town of Meiktila -- whose main building is shaped like an aeroplane -- researchers are utilising drone technology for a more scientific purpose.

The university has operated recent drone surveys to assess the impact of devastating monsoon floods that inundated huge areas of the country from July to September, affecting some 1.6 million people at their peak.

"Drone pictures can be very useful for prevention and measuring damage," said Thae Maung Maung, head of the department for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles.

He said the purpose of the surveys was to find out the scale of losses from the disaster, map the points where rivers had burst their banks and plot the best place for relief camps.

The new department is striving to keep up with technological advancements overseas -- no mean feat in an education system that was mired in underfunding and neglect for years.

Thae Maung Maung suggests enthusiasts such as Kyi Tha and his industrious customers will be crucial in helping Myanmar catch up with the rest of the world.

He explains: "We need to encourage young people's interest in technology so that we can keep developing."

Comments

0 comment