views

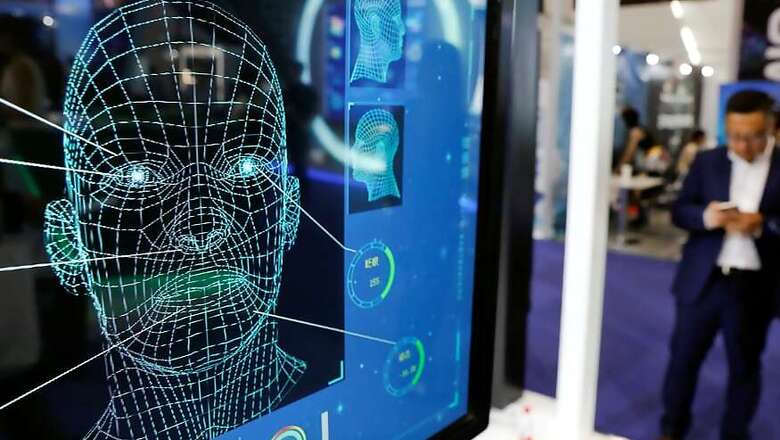

In recent times, the use of facial recognition tools by the Delhi Police has come to light. The centre-governed police force has, time and again, been using what is known as Advanced Facial Recognition Software (AFRS) during parades, and notably, once at a political rally. While the use of facial recognition by government agencies across the world is nothing new, what is perhaps alarming to note is where this is leading to, in terms of privacy of common people.

The fundamental working principle of Delhi Police’s AFRS tool is artificial intelligence, combined with manually curated information databases. In many ways, it is the same as Clearview AI, the contentious facial recognition tool that The New York Times recently reported on. Developed by Indian software firm INNEFU Labs, the system uses AI to sift through an infinitely stretchable data set to match individuals, thereby identifying them against their personal data. As its founder, Tarun Wig, explained to News18, the tool is quite versatile, and can suit anyone’s needs — be it a corporate firm, or a government agency. Wig states, “What AFRS does is detect and extract the faces out of an image. Every face is then converted to a vector of 512 values. Then, the software calculates the shortest distance between two vectors in a chosen database, and the closest matches are typically the accurate recognition of a face. This helps identify the person that a user wants to detect.”

That said, Wig maintains that beyond providing the software, he and his company have no knowledge regarding the database on which the AFRS AI algorithms work. He states, “The original database for the images depend on what the client feeds our tool. This is under the discretion of the customer, and if they want, they can even take data from Google, Facebook and other public sources, and ingest it into the system to recognise the faces.”

“We do not play a role in the implementation of the software and their uses, for any customer. The same holds true for Delhi Police as well. We only help maintain it with regular updates, but we are not involved in the operational tasks, since they do not want to reveal classified data to an external agency like us,” adds Wigs.

While Wig identified Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), India’s state-backed military research arm, as one of his clients for the facial recognition software, he refrained from naming other clients that have also sourced the tool from him. However, he broadly classified them as “financial fraud investigation agencies, corporate organisations and also law enforcement agencies.”

Context and global precedent

News regarding the use of facial recognition software truly came into the limelight right after PM Modi’s Ramlila Maidan rally on December 22. In days, weeks and even months prior to this, the Delhi Police were seen filming anti-government protests. As per reports, these footages were then fed to the AFRS system in order to extract identifiable faces of the protesters. The same was then matched against Delhi Police’s database to identify and segregate a select group of protesters, who were circled out as “miscreants who could raise slogans or banners” at PM Modi’s rally. The end objective was to ensure that no disruptive opposition voices interfere at the rally.

While this may seem like a one-off billing at the moment, it is likely far from it, and the reason appears two-fold. As N.S Nappinai, advocate of cyber laws at the Supreme Court of India, states, the first is the lack of a legal infrastructure that prevents the use of invasive technologies by agencies and state-backed organisations. She told News18, “The difficulty we have here is, firstly, India has no laws with respect to such forms of data capture. To be more precise, we don’t even have a law that states in what manner can data be captured in a CCTV.”

Elucidating further, Nappinai states, “Even at a basic level of data capture, we have not provided for laws for that. What we have today in India are two-fold – one is the law with respect to data protection, in terms of general data protection laws, which is just a very minimal, single civil/criminal provision under the IT Act. We also have provisions for monitoring, decrypting etc of online data. Here, we are talking about facial recognition technology, which is not regulated by any law in India.”

Interestingly, a report by Britain-based research firm Comparitech from back in September 2019 found out that New Delhi is among the top 20 cities in the world in terms of video surveillance. In its survey, Comparitech noted that there are nearly 300,000 CCTV cameras across the capital city of India, at an average of 9.62 cameras placed per 1,000 individuals. This, it is important to note, is almost in tandem with surveillance figures of provinces in China, which is infamous for its state-backed total surveillance regime.

Despite that, it is not quite clear if India’s facial recognition practices are quite in line with that of China and USA, at least as of now. The latter reportedly uses a privately developed tool called Clearview AI, which collates information from sources such as Facebook and YouTube to offer a database of nearly 3 billion individuals. This helps agencies extract an individual’s name, and subsequently gather further personal details about individuals.

In China, the IT ministry has made it mandatory for telecom operators to perform a facial scan of customers to validate their documentation, effectively showing the extent of public surveillance data that the government has in store. In Hong Kong, emergency powers were invoked by the government on October 4, 2019, making it illegal for people to wear a mask during the prolonged pro-democracy protests. In essence, this too worked like an instance of flexing the muscles of facial recognition, and the power that it gives authorities.

While India may not have the entire technology and legislation for it right now, what should alarm everyone is that it sits at the cusp of facilitating the widespread use of facial recognition by central powers.

End of privacy for the common man?

While India does not appear to have privatised its civilian databases yet, that is little consolation, and what India stands on the verge of losing is something very fundamental. As Nappinai states, “Today, what we have under the guise of data protection laws are only captured under the IT Act sections 43A and 72A. If we were to apply these two provisions, the first level of violation (in using facial recognition) is in using technology that is an intrusive surveillance tool, without any legal basis – in the sense that no law allows anyone to use it. What it violates, hence, is a fundamental privacy right.”

Unfortunately, as Nappinai explains, there does not appear to be much that individuals can legally act upon. As she states, “Today, there are no laws made by the parliament that allows for usage of such tools. At the same time, there are no regulatory processes which ensure protection of our rights, and guarantee that they will not be abused. There is literally nothing that either the law or the regulator has put in place to protect the citizens, before something is done that violates our rights.”

It is this very factor that shines all sorts of red lights on the increasing use of facial recognition in India. INNEFU’s Wig states that his company had received Delhi Police’s mandate after it had floated a tender to acquire facial recognition software to identify missing children. While its use case has understandably grown beyond this particular purpose, we now stand at a juncture where an individual’s right to privacy does not hold its ground. What India calls for today are data privacy regulations, clearer rights to information, and the ability to protect personal details — even as administrative use of facial recognition continue to rise across the world.

It is perhaps this that highlights the biggest irony, as data privacy posts flood the internet today, January 28.

Comments

0 comment