views

It's a new year and the harsh winter of the old has, at least temporarily, abated. However, India is still slurping down a politically piping hot alphabet soup: CAA, NRC and NPR being the key ingredients.

Every day, there are demonstrations across the country both for and against the Bharatiya Janata Party-led central government’s efforts to revise citizenship norms and identify infiltrators.

Even as the issue is being debated in every nook and cranny of the real and virtual world, often with cogent arguments like “anti-national”, “fascists”, “jihadis”, “Hindutva terrorists”, and the evergreen “go to Pakistan”, etc, it is certain that most political parties and their supporters would have their eyes fixed on two key poll battles to be fought in 2020: Delhi and Bihar.

It wouldn’t be far-fetched to infer that the outcomes of these contests may well decide the course India’s politics and policies will chart in the run-up to the 2024 parliamentary elections.

Pitted against its predecessor, 2020 comes across as an electoral lightweight. Last year saw the April-May general elections with concurrent assembly polls in Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim. These were followed by crucial contests for Maharashtra and Haryana in October with interesting conclusions. And, finally, Jharkhand saw elections in November-December. Not to mention the numerous bypolls held sporadically.

A Mixed Bag

The ballot battle season began with a bang for the BJP. The party and its allies picked up a spectacular victory in the Lok Sabha polls, confounding many psephologists and political pundits who had predicted a fractured mandate or, in some cases, a win for the so-called grand alliance cobbled together by opposition outfits.

While detractors had expected that the Narendra Modi government’s contentious moves such as demonetisation, less-than-impressive implementation of the goods and services tax (GST) regime, allegations of corruption in the Rafale fighter jet deal, as well as swirling unemployment and intermittent incidents of communal and mob violence would cost it votes, the ruling dispensation, in fact, bettered its already-stunning performance of 2014. The initial state elections followed a largely predictable path.

However, towards the end of the year, as Haryana, Maharashtra and Jharkhand went to polls, the BJP failed to retain power in two of these states. This despite doing well in the elections.

After emerging as the single largest party in Haryana that delivered a hung assembly, the ruling BJP managed to stitch up a post-poll alliance with the Jannayak Janata Party (JJP) to retain the reins.

It lost Maharashtra after a seeming victory as long-time ally Shiv Sena severed ties over power-sharing disagreements and formed the government with the Congress and Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) after days of intrigue and intriguing developments. In Jharkhand, the ruling BJP emerged runner-up. The pre-poll alliance of Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM), Congress and Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) formed the government, boosting opposition morale.

The Twin Challenge

Compared to the eventful electoral calendar of 2019, this year appears largely humdrum. However, the stakes will be sky-high when elections are held in Delhi, possibly next month, and Bihar, around October-November.

In the national capital, the Bharatiya Janata Party faces a tough challenge from the ruling Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) that swept the previous edition of the polls in 2015 as a fledgling outfit, burying rivals under a landslide. While AAP bagged 67 of the 70 assembly seats, the BJP could secure just three, and the Congress was reduced to an embarrassing nought.

It’s unlikely that history will repeat itself this time. The BJP and even the Congress seem set to improve their performance, but the ruling AAP may still manage to hold on after receiving plaudits for its work in education and healthcare as well as a clutch of populist moves.

Towards the end of the year, Bihar is expected to throw up another keen contest where the BJP is part of the ruling alliance led by the Janata Dal (United). The challenger is the somewhat nebulous mahagathbandhan, or grand alliance, primarily comprising the RJD and Congress.

What’s the Issue?

While a spiralling economic slowdown, accompanying unemployment concerns and an adverse global climate – worsened by the United States’ actions in West Asia – should perhaps be obvious themes for polls ahead, the political discourse right now is dominated by a clutch of moves made by the Narendra Modi government last year in keeping with its “nationalist” image.

The decision in August to strip Jammu and Kashmir of its “special status” under Article 370 of the Constitution and restructure the state into two union territories predictably triggered massive upheaval not just in the region but also other parts of the country.

The BJP justified the step and associated clampdown on communication and local leaders in J&K as an attempt to integrate the erstwhile state, gripped by militancy, into the country as well as usher in peace and development. Opposition parties and activists, however, have termed the actions “unconstitutional” and raised human rights concerns. The issue has garnered significant international attention. Legal challenges, too, are pending.

When the final list of the updated National Register of Citizens (NRC) – containing names and information for the identification of genuine Indian citizens in the state of Assam – was released in August, about 19 lakh residents were left out.

The process of refreshing the registry had kicked off around 2014 following a Supreme Court order. Several BJP leaders had announced to the public that the process would sift out lakhs of Bangladeshi Muslims who had allegedly infiltrated the state over the years. However, after protests over the exclusion of tens of thousands of Hindus from the list, the union home ministry declared that the NRC will be carried out again in Assam, along with the rest of the country.

The aim is to enable authorities to identify infiltrators, detain them and possibly deport them. However, detractors say Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhist, Jains and Parsis coming from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh won't be affected if they claim they have arrived in India after fleeing religious persecution before January 1, 2015 as they would be protected by the contentious Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) that became law on December 12 last year.

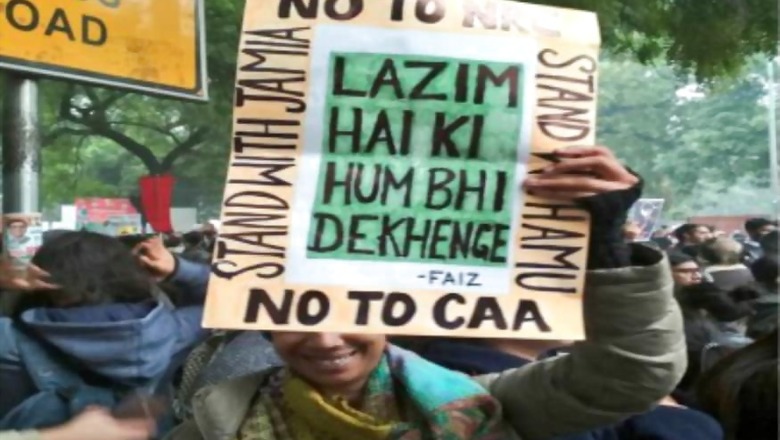

The Modi government revised the rules, promising relief to “persecuted religious minorities” from the three Muslim-majority countries who have sought refuge in India. The move has sparked widespread protests, led in many places by university students and intellectuals.

Violence has erupted in several areas, including in parts of Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka and West Bengal, with actions of both the agitators and the administrations coming under the lens.

Supporters of the BJP too have carried out counterdemonstrations. Critics say the law discriminates against Muslims and fails the constitutional principles of secularism and equality. Ruling party leaders, on the other hand, have accused the opposition of misleading the people and home minister Amit Shah has asserted that no Muslim who is an Indian citizen will be affected.

The central government’s decision to update the National Population Register (NPR) has also stirred up a controversy, with protesters calling it the first step towards implementing a nationwide NRC.

The NPR records personal details of everyone in the country who is a “usual resident” – a person who has resided in a local area for the past six months or more, or a person who intends to reside in that area for the next six months. The exercise has been carried out twice in the past: under the Congress-led government in 2010 and then in 2015, with the BJP in power, when it was linked to Aadhaar. The process of collecting information, simultaneously with the Census, is slated to start in April 2020 and end by September.

Triple Talk

Opposition parties and protesters have repeatedly sought to link CAA, NRC and NPR as a concerted attempt by the BJP and its affiliated right-wing groups to persecute Muslims and turn India into a “Hindu Rashtra” from a secular democracy.

Rivals, and even some allies of the ruling party, have expressed their disinclination towards carrying out these exercises in states they rule. Activists and intellectuals have argued that other disadvantaged sections such as many women, members of the LGBT community, dalits and adivasis would be hit hard by the steps, and everyone would be left chasing documents to prove their citizenship while braving bureaucratic entanglements. However, home minister Shah, as well as some other BJP leaders, have rejected these fears and stated that CAA, NRC and NPR are not linked to each other. They have also accused the Congress and other opposition outfits of being “anti-Hindu” and “speaking the same language as Pakistan”.

All this pandemonium comes at a time when India’s economic growth is slowing. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in its December monetary report said that the gross domestic product (GDP) would increase by just 5% in 2019-20 as opposed to 7.2% that it had predicted in April last year.

The Index of Industrial Production (IIP) recorded a -4.3% growth in October, which is the lowest since 2012. The Labour Force Survey, released in May 2019, showed a jump in unemployment rates in 2017-18. Many economists also contend that lingering effects of the Modi government’s 2016 demonetisation decision, to outlaw ₹500 and ₹1,000 banknotes in a stated bid to fight corruption and dry out terrorism finances, are still being felt with small businesses bearing the brunt.

They also blame the “inefficient” implementation of GST – that subsumed most indirect taxes in the country in 2017 – as a cause for the gloomy economic scenario in the country. The government’s recent attempts at reforms by cutting corporate income taxes and aggressively pushing a disinvestment agenda may somewhat repair the damage. However, with global concerns and uncertainty looming on the horizon as the United Kingdom (UK) gets set to withdraw from the European Union in early 2020, the United States (US) prepares for presidential elections in November, and the situation in restive West Asia takes a turn for the worse, India is staring at days of acute economic and diplomatic challenges.

Going Right

Many countries across the world have voted Right in recent years – the US, UK, Brazil, India, Poland, Hungary, etc, being prime examples. “Conservative” groups that propound traditional values, religious beliefs, national identity and protection against immigration have gained in popularity, emerging as strong challengers to “Leftists” and “liberals” who often support affirmative action for minorities, socialism, migrants, etc.

Social media recurrently turns battlefield for keyboard warriors from both sides. Ahead of the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP led by Narendra Modi managed to outstrip rivals by a wide margin in digital campaigning. While others have improved their game, the social media machinery of the ruling party and its associates, unsurprisingly, remains far ahead.

Digital avenues are also frequently used by supporters and information technology (IT) teams of all sides to spread propaganda and build false narratives. The problem becomes especially acute when elections are around the corner.

So while protesters on social media have hit out at the Modi government’s “Hindutva agenda”, “attempts to harass and silence minorities” and “destroy the secular fabric of the country” through exercises like CAA and NRC, pro-establishment netizens have called these steps an attempt to “right historical wrongs of the Partition era” and accused detractors of being “anti-Hindu” and hand in glove with “jihadis”.

Raising of Islamic chants during demonstrations have also been used as ammunition by right-wing adherents and even led to disputes among the protesters over the approach of the agitation. Activists have also adopted the legal route to challenge the government’s decisions.

Future Tense

The churning prompted by the Modi government’s 2019 decisions will continue in 2020 and beyond. However, as polls last year indicated, national themes don’t necessarily dictate outcomes of state elections where fundamental and local issues often take precedence.

For instance, the BJP lost Jharkhand where the campaign led by Prime Minister Modi and home minister Shah was peppered with mentions of “Kashmir”, “Ram temple”, “infiltrators”, etc. However, anti-incumbency, a non-tribal chief ministerial face in a tribal-dominated state, and controversial land acquisition rules apparently tilted the balance in favour of the opposition.

Delhi and Bihar are in no way untouched by the ripples created by the NRC-CAA-NPR controversy, with demonstrators still out on the streets and central ministers asserting that there’s no question of a rethink.

However, going forward, the big challenges for the ruling BJP will be repairing and guarding the economy through testing times as well as holding on to its allies, with some of them appearing spooked by its “expansionist” tendencies and “nationalist” agenda. If the results go in its favour, the party would know its strategy is working. If not, it'd likely be time for a change in tack. Because while politics of polarisation can make a regime’s loyal voters and supporters feel safe and validated, an economic downturn doesn’t pick sides.

Comments

0 comment