views

“The third wave of democratisation in the modern world began,” says Samuel P. Huntington (1991), “implausibly and unwittingly, at twenty-five minutes after midnight, Thursday, April 25, 1974, in Lisbon, Portugal, when a radio station played the song ‘Grandola Vila Morena’. The broadcast was the go-ahead signal for military units in and around Lisbon to carry out plans for a coup d’état that had been carefully drawn up by the young officers leading the Movimento das Forcas Armadas (MFA)” (The Third Wave-Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century, P.3).

Military coups are seldom known for heralding democracy. Rather, they are notorious for terminating them. Yet, this Thursday marks the 50th anniversary of a coup that unintentionally triggered the third wave of democracy. Huntington, better known in India as the author of The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order (1996), previously periodised the global cycle of rise, decline and resurgence of democracy. The first “long” wave of democratisation, according to Huntington, began in the 1820s with extension of the suffrage to a large proportion in the United States. This wave continued for a century until 1926, taking the number of democracies to around 29. However, a reverse wave caught up sooner in 1922 with the ascent of Mussolini to power in Italy. The rise of authoritarian regimes in Europe slashed the number of democratic states in the world to a mere dozen by 1942. The victory of the Allied forces in World War II initiated a second wave of democratisation which culminated by 1962 with 36 countries placed under democratic government. However, a reverse wave caught up again around 1962 bringing down the number of democracies to 30 by 1975.

Then a regenerative third wave of democratisation began in 1974. By 1990, at least 30 countries had made the transition to democracy, thereby almost doubling the number over the base year. Huntington’s book came out in 1991, the year the Cold War terminated. This led to dam burst of democratisation especially in Eastern Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. Currently, we are believed to be in an extension of the third wave. The “fourth wave of democracy”, a term used by Philip N Howard and Muzammil M. Hussain to describe the Arab Spring, is disputed.

II

Way back in 1974 with the West mired in the Cold War, it was Portugal that showed the way. A delinquent Hungary in 1958 and Czechoslovakia (of “Prague Spring” fame) in 1968 had been quickly disciplined by the USSR. They were made to junk their democratic aspirations. Though, during the Cold War, the USA valorised its actions in the name of democracy, there were serious lacunae in this narrative. Firstly, not every country in the Western bloc was democratic. For instance, Portugal, one of the founding members of NATO (Estd 1949), was ruled by a dictator Antonio de Oliveira Salazar since 1932. Neighbouring Spain, albeit not a NATO member, had been ruled by a more notorious dictator Francisco Franco since 1936. Secondly, several European nations that were flourishing democracies at home were ruthless colonisers abroad.

The hijacking of Santa Maria, a Portuguese passenger ship, by Portuguese and Spanish political rebels on January 22, 1961, brought global focus on the tyranny of Salazar’s regime. The hijacking was led by Henrique Galvão, a 66-year-old former Portuguese military officer, author and politician then living in exile in Caracas, Venezuela. Galvão, who had served as Inspector Superior da Administracão Colonial (senior inspector of colonial administration) in the late 1930s, and later represented Angola in the Portuguese parliament, had exposed the evils of his country’s misrule in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau in a scathing 52-page report (1947). He was imprisoned, but he fled feigning mental illness and later reached Venezuela. Dominique Lapierre, who clinched the first exclusive interview of Galvão, after the hijacking episode came to a close in Recife, Brazil gave his account in The Grandiose and Mad Dream of Twentieth-Century Don Quixote (A Thousand Suns, P.1-25).

A polyglot, scholar and humanist, Galvão passed away in Brazil in 1970, having the satisfaction of seeing Salazar retiring from his office in 1968 through not the end of his Estado Novo (‘the new State’). Salazar followed Galvão shortly to his grave, but not without appointing his political heir viz. Marcello Caeteno in Lisbon. Another African hero of Portugal emerged to warn about the imminent fall of Estado Novo. Antonio de Spinola (1910-96), a senior army general, and hero of Portugal’s wars of African insurgency, wrote a book Portugal e o Futuro (Portugal and the Future) which appeared in February 1974. Despite official censorship and red tape, the book briefly became the best-selling work in modern Portugal, next only to the Bible and the Lusiads (by Luis de Camões). Within a couple of months, a section of the officers in the Armed Forces rose in defiance, in what became a defining moment for the modern world.

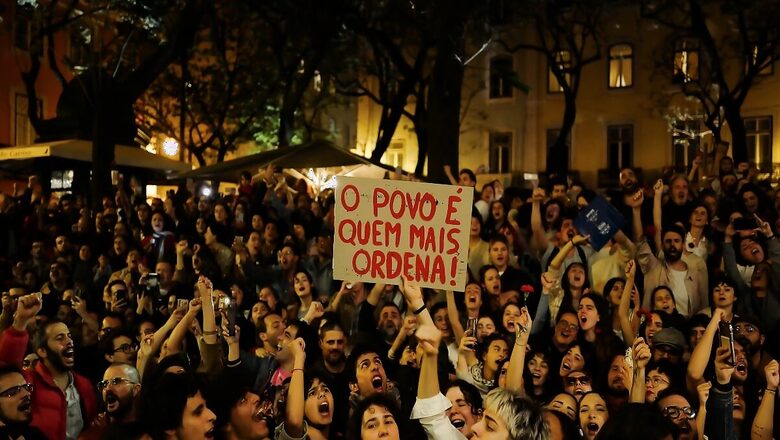

The fourth week of April 1974 being rain-drenched, the flower shops in Lisbon were full of red-coloured carnations. People came out on the streets and placed carnations on the muzzles of the guns carried by soldiers. The country was taken over, informs Robert Harvey (1978), by a left-wing group of army captains, similar in some respects to the cliques that seized power in Egypt in 1952 and in Libya in 1969 (Portugal: Birth of Democracy, P.1). The Movimento das Forcas Armadas – the Armed Forces Movement (MFA) – was born out of the army discontent, political ignorance, and barely understood Marxist ideology. Very few of the dissident officers, like Colonel Vasco Goncalves, had read anything much of the Marxist ideology or were committed Communists.

The leaders of the MFA proclaimed a three-fold agenda for change towards a new Portugal: democracy, de-colonisation of overseas empire, and developing a backward economy in the spirit of opportunity and equality. In the early 1970s, Portugal’s economy was still agro-centric, with the bulk of its population living in the villages. The country could have veered towards Communism like Russia and China before. There was indeed an attempt by radical leftists, including the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP), and its allies to take control between September 1974 and March 1975. However, the revolutionary Left, as Harvey tells, “ran up against the brick wall first of Church’s influence in northern Portugal and second of the system of land holding there” (Portugal: Birth of Democracy, P.3). The Peasants of Portugal, who comprised around 60 per cent of the population, rallied in the summer of 1975 to turn back the revolutionary tide, marked by seizure of lands in the south.

Meanwhile, a constituent assembly elected on April 25, 1975 — the first anniversary of the coup — drafted a democratic Constitution. The Carnation Revolution passed through four distinct phases before Portugal adopted a Constitution in 1976. It came effective from the second anniversary of the Carnation Revolution on April 25, 1976. Meanwhile, one by one, the colonies of Portugal were granted independence as colonialism was incompatible with democracy. Guinea-Bissau gained independence in September 1974, Cape Verde Islands in July 1975, and Mozambique in July 1975. Macau was offered to the People’s Republic of China, which has no democracy. The offer was refused then, but was accepted 25 years later in 1999. Angola, Portugal’s biggest colony, went into a quandary due to de-colonisation as there were at least three contending factions. A civil war broke out in the spring of 1975, which with certain interludes, continued until 2002. Similarly, when East Timor was granted independence in December 1975, the forces from neighbouring Indonesia occupied it. East Timor secured full independence in 2002.

Douglas L. Wheeler and Walter C. Opello, Jr, in their introduction to the Historical Dictionary of Portugal (2010), state that almost from the beginning of the 12th century as an independent monarchy, Portugal had turned its back on Europe and oriented itself towards the Atlantic Ocean. Portuguese kings gradually built and maintained a vast seaborne empire which defined Portugal’s identity. Whereas Portugal remained in Europe, it chose not to become of Europe. The Carnation Revolution on April 25, 1974, was the most decisive event in the history of Portugal in centuries. Portugal deliberately chose to move away from its oceanic mission and view of itself as an imperial power. Portugal finally decided to realign itself as being both in Europe and of Europe (P.25-26).

Huntington has described the wave of democratisation in the 1960s and 70s as largely a Catholic Christian wave, which was to overwhelm Latin America in the 1980s. This was because most of the protestant Christian nations had already moved into democratic orbit due to better economic conditions and educational opportunities. In the 1960s, the Catholic Church also began to change, particularly after the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) thus fostering a democratic outlook.

Huntington has underscored a shift in the policy of the Ronald Reagan administration. Initially, Reagan had targeted only Communist countries for human rights abuse and lack of freedom for their citizens. He had downplayed the moralistic approach of his predecessor Jimmy Carter. However, beginning 1982, Reagan was forced to acknowledge human rights violations and the lack of freedom that existed in authoritarian regimes as opposed to Communism. Huntington cites the foundation of the National Endowment for Democracy (1983) – which was established as an independent, non-governmental organisation through an act of the US Congress – as Reagan’s legacy. Reagan, thus fighting the Communist bloc to finish, could no longer turn a blind eye to non-Communist authoritarian regimes.

In 1974, whereas Portugal made the first move towards lasting democracy, it was apparently Greece that achieved it sooner. The fact was hailed as the ‘return of democracy to the land of its birth’. In April 1974, the military junta that had ruled Greece since 1967 collapsed, handing over power to civilian authority. Constantine Karamanlis was summoned from Paris to accept the leadership of the civilian government. He was majorly responsible for the Constitution of Greece (1975). In December 1974, the citizens of Greece abolished the monarchy, which had become part of independent Greece since 1830. This year marks 50 years of those tumultuous developments.

Interestingly, at least 64 countries (in addition to the European Union) representing about 49 per cent of the population of the world are going into elections this year. This includes India and the US, the world’s largest and second-largest democracies. The third wave of democratisation that began on the night of April 25, 1974, in Lisbon when a radio station played Grandola Vila Morena has no doubt succeeded. However, questions persist on the quality of democracy in the world.

The writer is author of the book “The Microphone Men: How Orators Created a Modern India” (2019) and an independent researcher based in New Delhi. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment