views

When the incumbent government of President Ibrahim Solih took office in Maldives in November 2018, many in India believed this signalled a new chapter in bilateral ties. Some of this was based on the extremely positive rhetoric towards India. President Solih has reportedly said, “India is the closest friend of the Maldives.” Foreign Minister Abdullah Shahid reflected the same sentiment when he said, “Relations with India are rock solid.”

These statements were in stark contrast with the approach of the previous government led by president Abdulla Yameen, who asked India to take back the two navy and coast guard helicopters, gifted by India a couple of years ago. It also refused to extend the visas of Indian military personnel attending on them, it is easy to see where the optimism for future closeness was coming from.

In addition, head of the ruling Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) and former president, Mohamed Nasheed indicated that Maldives would likely withdraw from the FTA with China (which again the previous government had rushed through and was a matter of concern for India). He further criticised China’s modus operandi when it came to seeking closer ties with the archipelago-nation. It then appeared that Maldives, which had tilted towards China under the Yameen administration, was now seemingly tilting back towards India.

The MDP leadership’s tilt towards India was noticeable even earlier during Nasheed’s regime. Nasheed’s government which took office in 2008 was the first multi-democratic dispensation after 30 long years of president Maumoon Abdul Gayoom’s one-party, one-person rule. Nasheed is at present the Speaker of the Maldivian Parliament, known as the People’s Majlis.

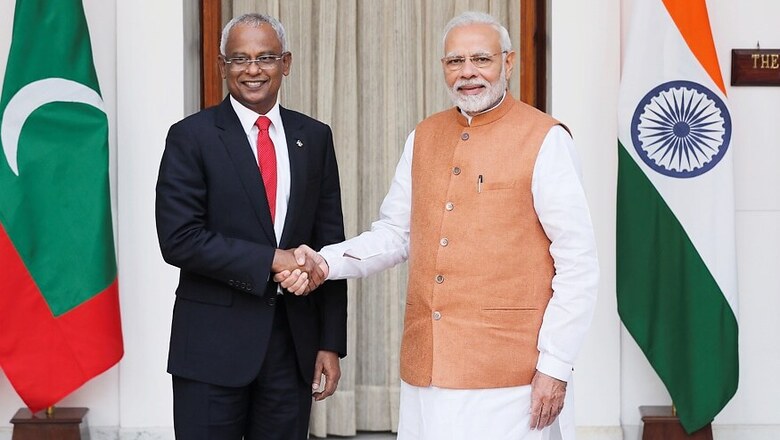

The pro-India rhetoric emanating out of the Solih government has been further accompanied by striking optics. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi became the only foreign dignitary to be invited to President Solih’s inauguration. Following this, many official visits have taken place between the two countries at the highest levels of government, including visits by President Solih, Speaker Nasheed and Foreign Minister Shahid. Several areas of co-operation have been identified and detailed discussions have taken place on issues as varied as maritime security, development funding, civil aviation and healthcare. The most dramatic of symbolisms has been the inter-linking of the coastal surveillance radar chain with the Indian navy (which had been stalled), vitally with the view of increasing maritime domain awareness.

Despite what appears to be a 180 degree turn in bilateral relations, it seems prudent for India to separate rhetoric from reality and ask itself how much does a country’s foreign policy change with a change in government?

Sri Lankan parallel

Looking comparatively at Sri Lanka and its various governments’ electoral promises of re-negotiating projects and agreement with China, it becomes clear that India should not read too much into what politicians say when they are in power and/or when they are criticising the administration in power while themselves being in opposition. Formulating a policy stance is one thing, ensuring a policy outcome is entirely different.

When former Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe came into office in January 2015, they did so with a mandate to investigate previous Rakjapaksa regime’s deals with China. Once in office, they went through with the much-criticised ‘debt-for-equity’ swap on the Hambantota port which resulted in the transfer of Hambantota on a 99-year lease to China.

This move was in turn attacked by the incumbent President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in his election manifesto which stated, “Hambantota port is a national asset and was defined as a strategic asset by us previously, and the intention was never to sell or lease the port for 99 years. We will make it a priority to revisit the already signed agreement with the Chinese government.”

However, in December last year, merely one month after coming into power, President Gotabhaya said he would not re-negotiate the lease agreement. He explained that it was purely a commercial deal and he did not want to convey a message to investors that commercial agreements would change every time a new government was elected to power.

Coming back to Maldives, President Solih’s team when they assumed office criticised the previous government for the loss of “billions of rufiyaa” (local currency) through embezzlement and corruption. They promised a forensic audit of deals made by the Yameen administration, many of these with Chinese state firms. Post-poll and throughout the past year, the messages coming out of the administration have been rather mixed. While Nasheed has continued to vociferously criticise China, Foreign Minister Shahid has been more cautious only stating that they intend to re-negotiate agreements made by Yameen, while never mentioning about repealing it pre or post poll.

Tactical or strategic?

If change in foreign policy is seen as essentially being of two kinds, tactical or strategic, we need to ask, has a change in government in Maldives merely brought about a change in tactics i.e. methods, or has there been a shift in strategy i.e. long-term goals?

And if we look closely at this question, not just in Maldives but also in Sri Lanka, or indeed any other neighbourhood nation, it could be argued that the change in their approach to India and China has merely been tactical and not a long-term strategic shift, or a dramatic resetting of relations. This seems to be the case with Maldives, unlike as was being optimistically welcomed.

It is plain speaking, realist balancing and not tilting that appears to be underway. If India is learning to approach Sri Lanka under Rajapaksa with “cautious optimism,” it will do well to adopt a similar approach in Maldives. This is important for several reasons.

Balancing not tilting

First, as India’s previous National Security Advisor, Shiv Shankar Menon argues, “We should get used to the idea that all our smaller neighbours, if they see India-China rivalry, will find it useful to deal with us in order to get things from the Chinese and deal with the Chinese in order to get things from us.” Nasheed often makes statements such as “We will be happy to maintain cultural ties with China. But we can’t afford to have defence cooperation.” Shahid on the other hand has been clear that, “China is also going to be one of the largest economies in the world. We can’t say that we will not have any relations with China because we have to appreciate what countries do for the people.” This should be seen more as a balancing tactic rather than a strategic tilt.

Secondly, though Nasheed, has often criticised Chinese activities in Maldives as land grabbing by China, this does not imply that he will not cut a deal with China in the future when the time/opportunity is deemed right. Another of India’s former National Security Advisor M.K. Narayanan notes that under President Yameen anti-India tendencies steadily increased and there was a pronounced tilt in favour of China. However, he also reflects, “After the MDP, headed by former President Mohamed Nasheed, came to power, for the first time anti-Indian forces within Maldives could muster some support. It was also Mr. Nasheed’s initial overtures to China that set the stage for Maldivian-China relations.”

Ideas, agents and structure

A country’s foreign policy is undoubtedly dynamic and therefore will change and shift over time. However, it is not shaped solely by governments in power spouting wishful rhetoric but by a complex inter-play of ideas, agents (state and non-state) and structures (domestic and international). In the order to understand the evolving foreign policy of Maldives, which is also an evolving democracy, India must pay attention to all these factors. India can definitely welcome the return of a government that wants to engage, yet it needs to go beyond the ‘India First’ rhetoric which has been repeated by various governments over the years. India must pay close attention to the structural constraints affecting Maldives both at the domestic and international levels.

The structure of the international system and balance of power tend to limit the foreign policy choices of smaller states. Normally, this would mean we are likely to see more continuity in the way Maldives engages with India and China, despite the change in government. But we are now living in a present and post-pandemic world where coronavirus is at the helm of world affairs. We all know that this is just not a public health crisis, but one that will affect every choice a government makes in future. Therefore, as the major powers reflect on their policy priorities, new choices will open for both India and Maldives.

Domestic structural constraints on the other hand refer to the socio-economic, political and institutional setting within which foreign policy is framed. These constraints are numerous and affect foreign policy choices at varying levels. In Maldives these constraints range from the challenges to the judicial system, limited opportunities for job creation and youth unemployment, physical vulnerability due the challenges of geography and the rise in sea-levels, and also dealing with security threats from non-state actors. The structure of its economy and restricted options for economic diversification also shape foreign policy choices. COVID-19 adds yet another layer of complexity. Given that its tourism sector accounts for 28% of its GDP and 60% of its foreign exchange earnings, the impact of the spread of COVID-19 in China, Europe and India has been devastating with Maldives becoming the worst hit in Asia in terms of lost tourism. India must pay close attention to all these emerging challenges. Dramatic changes await the foreign policy choices of the archipelago nation as well as of the world beyond it.

This article first appeared in ORF.

Comments

0 comment