views

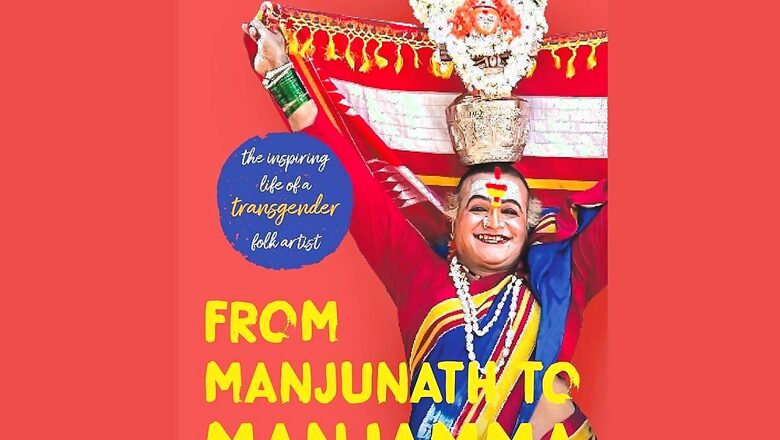

I finished reading the book, From Manjunath to Manjamma, nearly a month back. The book kept haunting me with its raw emotions expressed simply by a simple woman Manjamma. It haunted me because it hurt me to see how we, as a society, treat transgenders, who from birth are from tritreeya prakriti (third gender). What must they be going through, being taunted, abused, ridiculed and treated shabbily by fellow students and even the family that is ‘horrified’ at this deviation in the family? So finally, I decided to write this review.

Our ancient literature tells us that Bharatiyas accepted the people of ‘triteeya prakriti’ as a part of normal social life and never discriminated against them. In fact, ‘hijras’ are supposed to be auspicious and they visit and dance in households at the time of a child birth or wedding. Families seek their blessings and are also afraid of their ‘curse’. It is true that no ancient Indian texts from Vedas onward consider sexual deviation as criminal. Sushruta Samhita goes to the extent of saying that sexual inclinations of a person are cast at the time of conception.

We talk about ‘Ardhnareeshwara’ — half male — half female form of Lord Shiva. The idea of this imagery is that each human being carries within her/him qualities of both a female and a male. Predominant ‘prakriti’ or nature defines the behaviour of that person. No person in our history has been punished for his/her sexual deviation. But somehow, with influence of invaders’ ideologies our society to became narrow-minded and we see the torture that transgenders have to go through. Manjunath’s story reflects fossilisation of our own traditions and cultures.

The book made me feel better because it told me how we Bharatiyas have treated people with ‘triteey prakriti’ with empathy and love and have given them their due place in the society with respect. The fascinating story of the community of Jogathi and its venerated process of initiating a transgender into their community made me respect our Hindu society that finds solutions to such issues.

The journey of Manjunath from Manjunath to Manjamma and then on to Padmashri Manjamma is heart-breaking, awe inspiring and finally ennobling. Her refusal to give up and give in to conform to social norms is an extraordinary tale of courage.

That the Karnataka government recognised her talent and commitment to the tradition of Jogathi Nritya (dance) shows that we have not entirely forgotten our traditions. Her elevation to the post of chairperson of Karnataka Folklore Academy shows the egalitarianism and dignity of an individual remains the bedrock of our civilisation. Distortions in our thinking from the western civilisation can still be repaired. Recognition of her work with a Padmashri is not her recognition but, in a way, acceptance of our mistakes as a society and efforts of the Central government to overcome social taboos. They are in line with its progressive legislations for the LGBT community initiated by this government. A Hindutva government has helped remove the criminality of homosexuality – a legacy of colonial mindset and Abrahamic religions, the legislations to help homosexual partners have common bank accounts, etc, introduced recently reflects our Hindu thinking.

Most transgenders become aware about the conflict between their physical body and the mental body as they grow, not knowing how to cope with it, reconcile with their real gender identity, and share their dilemma with their family and friends. While the girl in Manjunath wanted to dance with abandon in school programmes, his family felt ashamed that she dressed like girls and danced like girls.

Describing her transformational days, Manjamma in her teenage, “I started bleeding, as if I was menstruating. My undergarments and lungi would be stained with blood but there was no pain. After a few months it stopped.” When (at that time) he was checked by the doctor, everything physically was fine. How do you explain such extraordinary nature defying incidents.? Most of us are not aware that there is a ritual of “getting beads tied (mutthu kattisikollodu)” for the person who is finally accepted into the fold of Jagathis. Even after being initiated into the Jagathi community, there was no acceptance at home. Finally, she even tried to commit suicide by consuming pesticide. When she ended up in hospital, none from family came to take her back. There was no food to eat when she finally left the hospital, family would not offer her any. So, the bed crumbs saved from the hospital, dipped in water were her only food for many days. She admits she cannot forget those days of immense isolation and rejection.

After much penance and following a couple of gurus she could learn the art of Jogathi Nritya and life settled a little after that. But knocks from fate never ceased: The sorrow of knowing that family wants their money or home but there is no one in the family to cremate a Jogathi when she dies. Despite traditional acceptance, society does not accept them even in death. It is a story that will leave you disturbed.

There are sections in the book that will choke your heart, disturb you and pain you. However, by the end of the book, you will feel cleansed of many negative emotions. Manjamma not only shares the travails and successes of her life, but she also goes on to provide solutions to the problem of transgenders, revival of our ancient traditions that gave transgenders a life of respect and new approach to this issue add value to this book.

I hope this book will also sensitise the readers to the fake narrative of ‘Fluid Gender’, that at the last count I had, talked of 108 genders! Their unscientific pronouncements and illogical demands have actually harmed the struggle of both homosexuals and genuine transgenders, as well as rights of women for that women have waged battles for years. They suddenly find that their struggle has been suppressed or sidelined under these artificial constructs.

From Manjunath to Manjamma will help us think clearly about this issue and ponder over how to help transgenders lead a life of dignity, open our hearts to them and sensitise us to their struggles and pain they go through. This book is a wonderful tool that will help crystallise their problems and help people at large to not just have empathy but also sensitivity.

Author Harsha Bhat deserves to be complimented for picking up this subject as her first attempt at writing a book. She has taken pains to travel back and forth to Manjamma’s village to make elaborate notes over the conversations with her and put her life’s story on paper. The book needed a little better editing. It might have come out even better if Harsha had used her creativity that went beyond honest translation and had made the flow of the story better. Raw emotions and language have their own power, but hamper easy reading. Probably, the idea was to let the story remain raw — as raw as the inner power of Manjamma. Be that as it may, Harsha’s courage must be appreciated to take up this difficult task. I hope she finds more such complex topics to work on.

The reviewer is a well-known author and political commentator. He has written several books on RSS like RSS 360, Sangh & Swaraj, RSS: Evolution from an Organisation to a Movement, Conflict Resolution: The RSS Way, and done a PhD on RSS. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment