views

New Delhi: For those shopping at Meerut’s Sadar Bazar, the evening of May 10, 1857, began like any other. Britons were milling around shops in the sweltering North Indian heat when a group of Sepoys (soldiers) swarmed the market. From there on, it was a bloodbath which went on to be recognized as the first revolt for independence. The anger of around 100 years of exploitation and humiliation under the ‘Company Raj’ had reached a tipping point on this day, 160 years ago.

For the Indian Subcontinent, the uprising of 1857 was perhaps the most significant development of the century. It was, after all, dubbed ‘India’s First War of Independence’. News of the uprising, which began from Meerut, spread across the country. Soon, sepoys in Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Ambala and other cities were at war against the East India Company. Farmers, women, clerics, ascetics and common people all joined the fight.

The news, however, did not reach London for over a month. Did Britain fail to fathom the scale of the uprising? How long did it take for the British press to realize that the East India Company was losing control of the subcontinent?

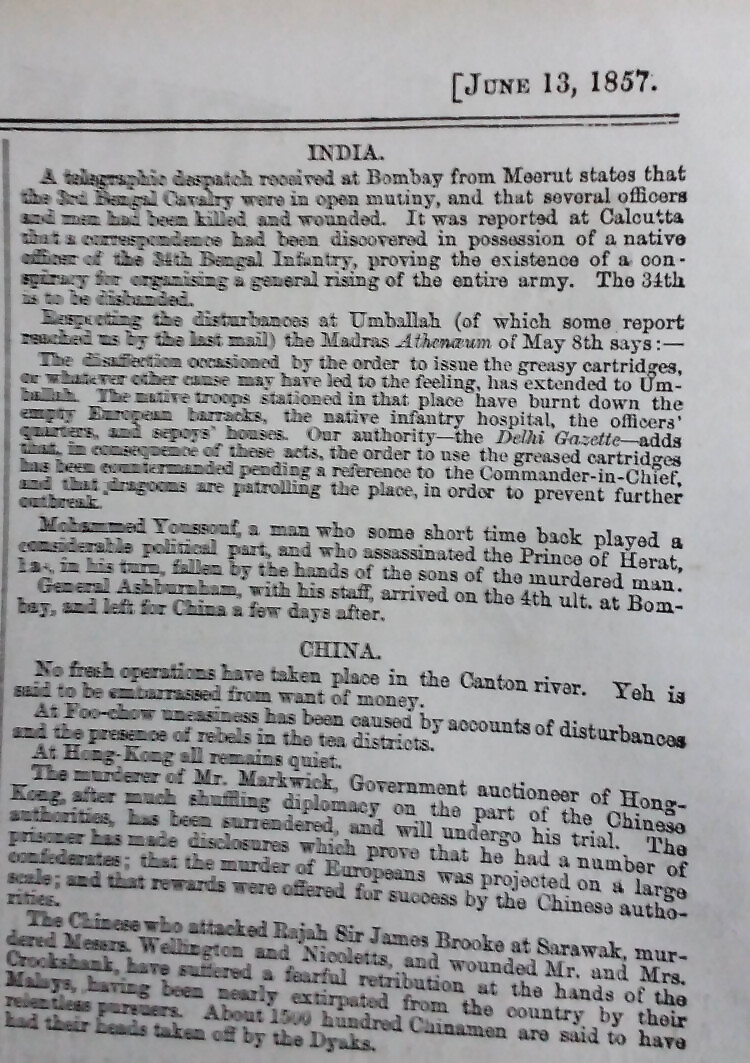

June 13, 1857: London wakes up to news of a ‘mutiny’

On June 13, over a month after Indian sepoys of the East India Company rebelled against their English superiors in Meerut and laid siege to Delhi, London woke up to the news. Since news in the 19th Century was dispatched over telegram, which had to be transported by sea, it took that long for the updates to reach UK.

For the Indian Subcontinent, the uprising of 1857 was perhaps the most significant development of the century.

An article in the Illustrated London News, dated June 13, 1857, read, “A telegraphic dispatch received at Bombay (now Mumbai) from Meerut states that the 3rd Bengal Cavalry were in open mutiny and that several officers and men had been killed and wounded. It was reported that at Calcutta (now Kolkata) a correspondence had been discovered in possession of a native officer of the 34th Bengal Infantry, proving the existence of a conspiracy for organising a general rising of the entire army. The 34th is to be disbanded.”

News of the uprising, which forced Queen Victoria of England to end Company rule, did not exceed 300 words.

Amit Pathak, Meerut-based historian and author of ‘1857: Living History’, had purchased original news clippings from the Illustrated London News, says, “The way the British press treated the news makes it clear that they thought it was a small-scale rebellion. It was either because the full details had not reached them, or because they were so confident in their own ability that they thought the mutiny would be easily quelled.”

Bias of British Press

As telegrams continued to pour in from Bombay, the British public started to realise the full extent of the revolt. A casual dismissal of the uprising turned into outrage at the news of “atrocities” against Europeans and anger at the British government for keeping the public in the dark.

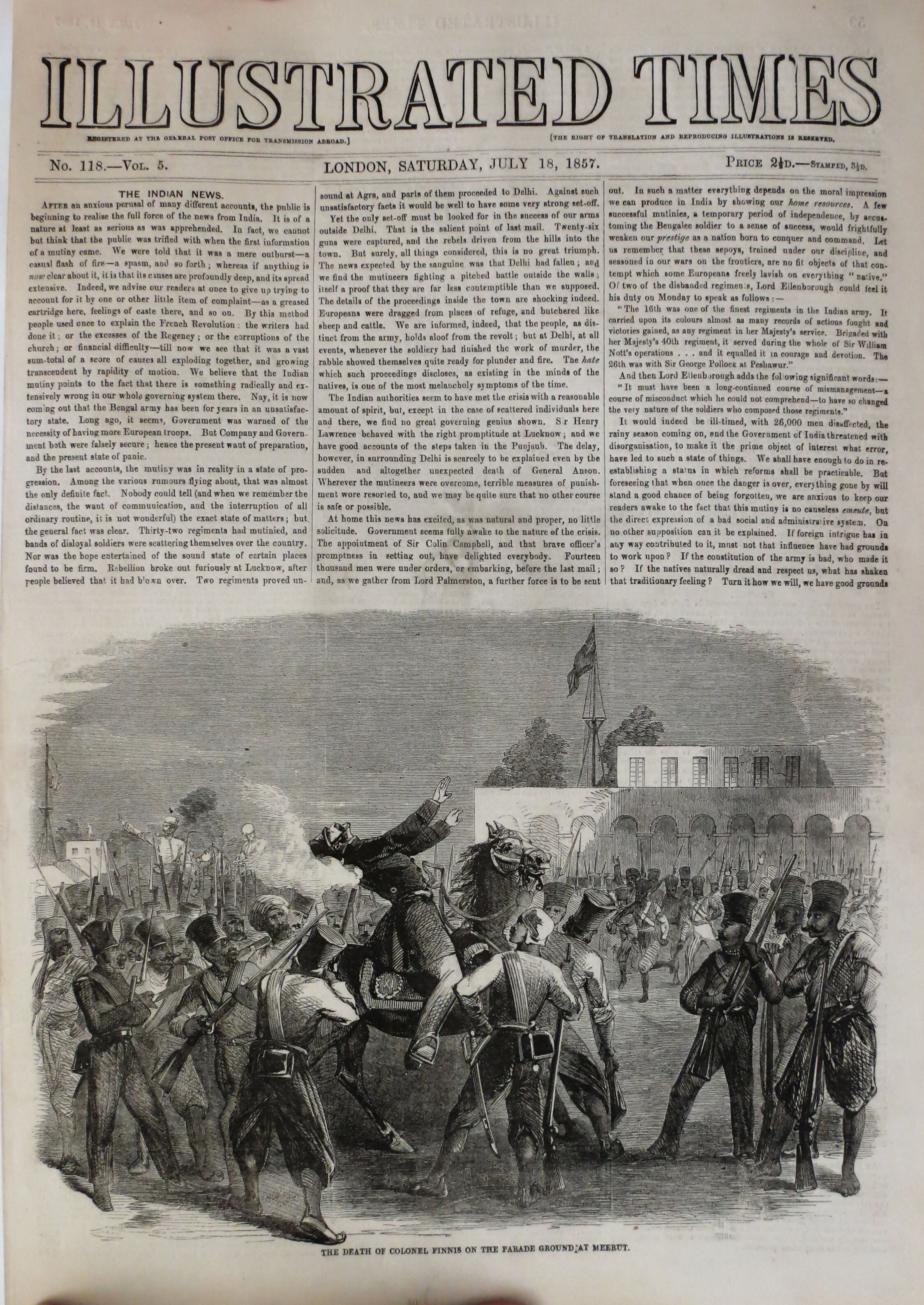

The Illustrated London News’s coverage went from a tiny news brief to a full-page scathing editorial. A piece published on July 18 read, “After an anxious perusal of many different accounts, the public is beginning to realise the full force of the news from India. It is of a nature at least as serious as was apprehended. In fact, we cannot but think that the public was trifled with when the first information of the mutiny came. We were told that it was a mere outburst – a casual flash of fire – a spasm, and so forth; whereas if anything is now clear about it, it is that its causes are profoundly deep and its spread extensive.”

According to Pathak, the mutiny caught everyone in England by surprise. “Indians were considered docile and nice people. There was outrage at alleged atrocities committed against Europeans, especially women and children, but there was another significant development. The British press called out the East India Company for its bad governance. Pressure from the press was one of the reasons the Queen was forced to end company rule. After the mutiny, India was governed directly by the Crown.”

The Illustrated London News’s coverage went from a tiny news brief to a full-page scathing editorial.

The July 18 piece goes on to illustrate Pathak’s point. “We believe that the Indian mutiny points to the fact that there is something seriously wrong in our whole governing system there. Nay, it is now coming out that the Bengal Army has been for years in an unsatisfactory state.”

What if the uprising took place in digital age?

The technology prevalent at the time did not allow news to travel fast. But what would have happened if the sepoys had risen in revolt in the 21st century instead?

Pathak believes if updates were sent out instantly, the sepoys would have lost the war before they even reached Delhi to see the Mughal Emperor. “The reason for their initial success was because they had the upper hand as the British officers were caught unaware. One of the first things that the sepoys did very smartly was that they had cut the telegraph lines. Only half a telegram had reached Agra and no news had reached Delhi at all. If news had spread, reinforcements from all corners of India would have gathered at Delhi swiftly to quell the rebellion. They would have secured their superior firepower and been better prepared for the Siege of Delhi.”

Troops from England, too, would have arrived much earlier. “It took around 45 days for a detailed write up to reach from Bombay to London. It would take even longer for troops to reach India. The fastest way for them to reach India would have been to board ships to Alexandria in Egypt, cross over by land to Port Suez by the Red Sea and then board a ship to Bombay. It was only by August that the reinforcements finally arrived. And it was by mid-1858 that the British were able to control the situation. Things would have gone very differently in the digital age.”

Comments

0 comment