views

Planning Your Story

Identify your style of humor. When you sit down to write a funny story, you need to be aware of your personal style of humor. If you're trying to write in a style that doesn't fit your strengths as a comedian or storyteller, then your story may not be as strong as it could be. There are many different types/styles of humor. Some of the most popular include: Observational humor involves pointing out humorous or mundane situations in everyday life, as well as poking fun at others, often in a playful manner. Anecdotal humor focuses on humorous personal stories, which may be slightly embellished for comedic effect. Burlesque involves caricature and imitation, often with exaggerated characteristics. Dark (or gallows) humor involves death and other types of misfortune, often with a comically pessimistic viewpoint. Dry (or deadpan) humor uses a lack of emotion or expression to deliver funny material. Farcical (or screwball) humor uses skits or satire involving highly improbable circumstances, often with exaggerated reactions and frantic movements. High (or highbrow) humor involves cultured or intelligent topics/themes. Hyperbolic humor uses excess and exaggeration for comedic effect. Ironic humor involves either a split from normalcy or a situation in which the audience knows more than the characters know. Satirical humor points out a person's or society's weaknesses and downfalls with comedic effect. Self-deprecating humor features the comedian or storyteller making fun of themself. Situational humor employs some elements of farce, screwball, or slapstick comedy to make fun of everyday situations. Slapstick involves acting out mock violence or bodily harm through physical comedy.

Decide what your story is about. Before you can write a funny story, you need to have some idea about the story itself. It's not enough to have jokes or a funny scenario; the story needs to be strong so that it can support the humorous elements. Brainstorm ideas. If you're stuck, try watching funny movies and reading funny stories for inspiration. Write down strange or funny situations you've experienced in the past. Don't worry about making them funny right now. Just write out what you can remember about the experience and why you found it humorous. Choose a vivid setting that your audience will be able to imagine. They'll be better able to understand the humor if they can imagine the setting. The setting itself doesn't have to be funny (though it can be), but it should make sense for the characters and plot you're creating. Think about what you ultimately want your story to say. What will the overarching point of your story be? Is it a story about overcoming adversity? Is it a commentary on modern society?

Create a conflict and tension. Ideally, the tension and its resolution in your story should illustrate some aspect of human nature. Once you create your story's conflict, tell your readers the stakes facing your characters if they don't resolve it. Your readers will find the events of your story more interesting if you create conflict and tension that move your plot forward. Your story's conflict should create tension. Because it's a funny story, that tension may be funny itself, or the circumstances around it (how it builds, or how it is resolved) could be humorous. Most commonly, the way you resolve the tension in a comedic story will provide much of the humor. Additionally, always create some kind of stakes. A good story has some outcome on the line for the characters, which may be funny or tragic (but needs to be realistic). Sketch out the rising action, climax, and falling action. The climax is typically the high point of tension, and the rising and falling actions build up and relieve that tension (respectively). In the Chris Farley movie Tommy Boy, for example, the conflict is the risk that Tommy's evil mother-in-law and her secret husband will sell the business and get away with it. The tension arises from that conflict as the narrative builds to a point where everything must be resolved.

Choose a point of view. Choosing a story's point of view requires you to decide who would tell the story best, and how that information should be delivered. The main options at your disposal are first person, second person, and third person. There is no objectively right or wrong choice, because it all depends on what you think works best for your story. First person - this is where a story is told using "I," "me," and "mine." It's one character's subjective take on the events of your story, and the narrator is usually either the protagonist (the main character) or a close secondary character telling the protagonist's story. Second person - a story told in second person is told directly to "you" (without any "I," except in dialogue). The reader imagines herself as being part of the plot, with the action written in the following manner: "You follow him down the stairs, and you're surprised at what you see." Third person omniscient - this is where an omniscient (all-seeing and all-knowing) narrator delivers the story, without ever referring to an "I" or addressing the reader as "you." The reader comes to understand the events, thoughts, and motivations each character experiences. Third person limited - while told in a similar narrative style as third person omniscient, third person limited only offers insights into the thoughts/feelings of one character. The narrative follows the protagonist and delivers the world as he/she experiences it.

Set up funny situations. Choose an initial funny setting or incident, then build the rest of your story's plot off of that idea. For example, an inappropriate or unusual setting or event can make great comedy. As another option, use a classic comedic situation, like having a mistaken identity, being in the wrong place at the wrong time, or inserting a character or object into a situation where it doesn't belong. Let's say your story is about a man who is invited out to lunch. He shows up to lunch wearing a t-shirt, shorts, and flip flops, plus he brought his dog. However, the restaurant turns out to be an upscale 5-star eatery with a dress code. Although the situation itself might not seem funny, it's a great source of humor because it flips your expectations. By contrasting the classy restaurant with the man's casual attire, you can set the scene for readers and help them relate to the character's funny situation. Larry David Larry David, Comedian Mine your own unique experiences for inspiration. "It's always good to take something that's happened in your life and make something of it comedically."

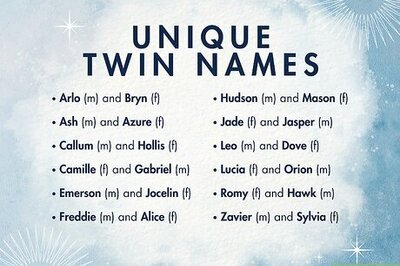

Create funny characters. Good characters are vital to any story, and funny stories are no different. It may be more difficult to make a character well-written and funny, but it's not impossible. Focus on making the characters funny in their own way, whether it's because of the way they look, the way the talk/behave, or the situations that they find themselves in. Remember that there are many different kinds of humor. Your characters might be sarcastic, dumb, observant, and so on. The Three Stooges program offers a great example of funny characters. Their style of humor was predominantly slapstick, but much of the humor arises from their personalities, quirks, and reactions to both situations and each other. Let each character's humor arise from his or her personality, and be consistent with that character's traits. Don't worry about crafting the character's entire backstory yet (though you will have to do this once you begin the actual writing process). For now, focus on getting a clear idea in your head about what the characters look like and how they behave.

Writing the Story

Write an engaging first paragraph. By the end of the first paragraph, many readers will decide whether to continue reading the story or to give up and set it aside. A strong, engaging beginning is vital, then, if you want your readers to continue through the rest of your story. A good first paragraph should hook your reader's attention and interest. Don't worry about making the beginning funny; you can always insert humor during the revision process. Focus on engaging the reader by evoking the scene or situation. Try incorporating something unusual, something unexpected, a striking action, or an interesting conflict in the first paragraph. This creates tension and a sense of urgency, and the reader will want to continue.

Develop your characters. Any story, whether it's fiction or nonfiction, needs well-developed, three-dimensional characters. Don't settle for flat stock characters that everyone has seen before. Give your characters some personality, and if you're writing about real people you know make sure you bring them to life by describing their appearance, mannerisms, and other facets of their personalities. Always know more about a character than you'll ever actually use in the story. Flesh out the character in your head before you begin writing so that he or she will feel real to you and to the reader. Brainstorm what makes this character unique. Consider what he looks like, his hobbies, temperament, phobias, faults, strengths, secrets, defining moments/memories, etc. Make sure you convey four main characteristics to your readers: a character's appearance, actions, speech, and thoughts. Any other details can support those characteristics, but without those four your character may not come to life for a reader.

Work in funny anecdotes. Anecdotes are short, personal stories that convey something funny or meaningful. An anecdote is the short personal experience you tell your friends about over coffee or cocktails. Some of the best anecdotes are pithy, punchy, and interesting. Many people find that humorous stories/anecdotes are funnier than an actual joke. Jokes can elicit a laugh, but they're short lived and generally less memorable than a true story of embarrassment or mistaken identity. Don't just stop at your own personal anecdotes. Mine your previous conversations with friends, family, and coworkers, and try to incorporate their moments of humor. David Sedaris is a great comedic writer who uses personal anecdotes as a jumping off point to talk about the comedic (and at times tragic) aspects of human nature and experience. Try reading his essays online or pick up one of his many books for inspiration and examples.

Show, don't tell. You may have heard the old adage, "Show, don't tell." It means that there is more power and strength in describing a situation or setting to the reader, rather than simply telling the reader what's happening. For example, instead of using the old line, "It was a dark and stormy night" to tell the reader that it was raining outside, you might describe the sound of the raindrops hitting your roof, the squeak your car's wiper blades make, and the way a flash of lightning lit up the hillside as though it were daylight. Use specific details that illustrate the point you're trying to make. Instead of telling the reader a character is sad, show him crying and running off to be alone. Let the reader assemble the pieces of the scene or event on her own. This will help the reader feel your emotions more genuinely. Be specific and use concrete descriptions. Avoid the abstract or intangible, and instead focus on something the reader can imagine seeing, hearing, touching, or feeling.

Revising Your Story to Make It Funnier

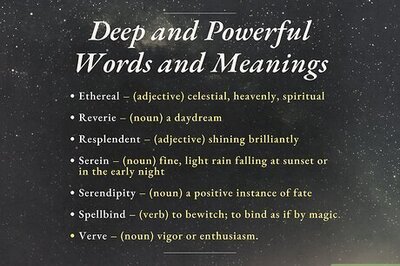

Try incorporating comedic descriptions. Descriptions can be funny in themselves, and they can also set the scene for a funny action sequence. Your comedic descriptions may detail two things that shouldn't normally go together, or you might focus on describing the absurdity of the way a person, place, or thing appears. Find a new and interesting way to say something familiar. This can be very funny, and it also keeps your readers on their toes. Try using funny adjectives in your descriptions. Again, the focus should be on saying something in a way that surprises or delights the reader. Many comedians find that words with a hard "k" sound (like "car" or "quintuplet") simply sound funnier. The same is true for words with a hard "g" sound (like "guacamole" or "garrulous")

Write funny comparisons. A good comedic comparison should describe how two things are related, but it might do so in a funny or unexpected way. A comparison joke should still make the point you're trying to make, but it does so in a way that makes the reader laugh. Use similes and metaphors that evoke familiar images. For example, you might say something like, "Making it through this week will be about as easy as painting an elephant's toenails; I hope I make it out alive." A simile is a comparison that uses "like" or "as". An example of a simile would be, "Your love is like a flower." A metaphor is a comparison that describes something as though it were actually something else. An example of a metaphor would be, "My heart is a pounding drum." A humorous comparison might be something like, "He danced like a horse drunk on wine...but he was still a better dance partner than I was." Try out different comparisons until you find one that is effective and makes you laugh, then test it out on someone else to see if they find it funny.

Make fun of yourself. If you're writing about how everyone in your family or your workplace is dumb and ugly, your readers will probably think you're mean and unfairly critical. However, if you make yourself the butt of your jokes, your readers will understand that you're exaggerating or singling out yourself for comedic effect, and it won't come off as mean or judgmental. It's okay to poke fun at others close to you (your friends, family, etc.). But if you just hammer on them without taking a jab at yourself it may come across as mean or arrogant. Worrying about offending others can stifle your comedy. Making fun of yourself lets readers know it's okay to laugh along with you, since no one else is being unfairly targeted. Talk about personal experiences, things that have happened to your friends/family/coworkers, and any other aspects of your life that have brought you funny stories - just be sure to bring the mockery down on yourself at least as much as you make fun of others.

Never tell a reader that something is funny. You wouldn't tell a joke and then explain, "That was supposed to be funny" - or at least you wouldn't need to explain it if your audience found it funny. The same is true when you're writing a funny story. If you have to tell your readers that something is funny, the joke probably flopped. Let your readers discover the humor of your situation on their own. That will make for stronger storytelling, and it will let your jokes land better for the reader. This ties in with the "show, don't tell" rule. Just as you showed your reader a scene or a character with skillful description, you should likewise show your reader the funny description or action sequence without saying it was funny.

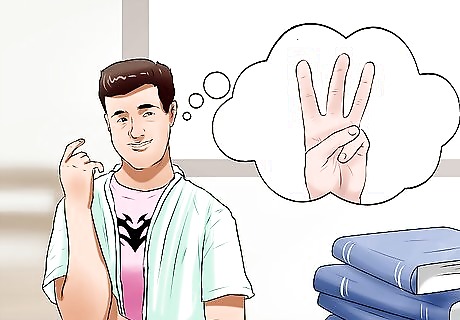

Remember the rule of three. A lot of written comedy relies on setting up the reader's expectations (perhaps by establishing a pattern, for example) and then subverting those expectations. The reader will realize that the story did not go the way she expected it to, often with comedic results. One way to set up this type of humorous outcome is by using the rule of threes. The rule of threes relies on pairing two similar ideas/events/people together so that the reader recognizes a pattern forming. Once the reader expects the pattern to continue, you deliver a third idea/event/person that goes in a direction the reader did not expect. This works best with groups of three because it's a low enough number that most people will easily remember each item, but it's also just enough items that the reader will come to see a pattern and expect it to continue. As an example of the rule of three, you might say something like, "I don't know what's wrong with my dog; I've taken him to obedience classes, I learned how to discipline him, but he still hasn't helped me meet anyone at the dog park."

Practice using comedic timing. Comedic timing may mean setting up a series of events to unfold at a certain time and place, but it also means letting a joke, funny word/phrase, or punch line land in a humorous way. It's all about delivery and how you set up the joke or story. Comedic timing may involve an element of surprise, misdirection, or simply building suspense in order to let a funny line land at the best possible moment. An example of comedic timing might involve writing something like, "This dating tip always works and it will drive your partner crazy...except for when it fails."

Don't overdo the humor. If you're writing comedy for the first time, you may be tempted to pack in as many jokes, funny descriptions, and comedic situations as possible. But sometimes, too many humorous elements can be overkill, and it ends up detracting from the story's strengths. Try to balance the humor, and make sure it's relevant and serves your story (instead of your story serving the humor). Don't lose focus of what your story is actually about. It can be a very funny story, but it needs to be a strongly-written story first. Try to limit the use of humor throughout the story. That way, when a funny line really lands well, it will be memorable and exceptionally funny.

Edit your story. As you make revisions, like inserting more comedy (or scaling back the comedic elements), remember to do a thorough edit. Editing a story like this will require you to comb through each line and look for typos, run-on sentences, sentence fragments, weak descriptions, cliches, and other problems in your manuscript. It may be helpful to set your story aside for a few days before approaching it to edit and revise. When you look at your story with a fresh pair of eyes, you're more likely to catch the mistakes that you might otherwise have missed. Consider having a friend read your story, and ask for feedback. You should also ask your friend to circle or underline any typos, grammatical/syntactical errors, and weak or unresolved segments of the plot.

Comments

0 comment