views

Using Military-Style Training Techniques

Take a patient, positive approach that has no timetable. You might assume that training methods inspired by the military must be harsh and rigid, but that’s not the case with dog training. Military trainers don’t set specific timetables for the dogs to achieve certain benchmarks, and they don’t try to force the dogs to learn. Before they can take on the job, military dog trainers must demonstrate patience and understanding when working with dogs. Just like people, some dogs learn faster than others, and some dogs may never be able to learn everything you try to teach them. Your dog has the best chance to learn both quickly and effectively if you avoid arbitrary goals and a negative training environment. Not everyone is cut out to be a dog trainer, either. If you know you don’t have the patience or positivity needed for the role, hire a professional dog trainer who utilizes military-style techniques.

Build a positive relationship with the dog right from the start. It’s important that you quickly show yourself as the “alpha”—that is, the leader in your pairing—but that you do so through camaraderie, not threats or force. If you don’t already have an established relationship with the dog, spend a few days or even weeks taking care of its needs before you start training it. Show it that you are the provider who can be relied on. If you already do have a relationship with the dog, spend a few days emphasizing your roles as provider and leader. Take care of feeding, walking, cleaning, and so on yourself, without treating them like unwanted chores. Daily grooming is a good way to both build a positive bond and check the dog for potential medical issues. Military trainers typically groom their dogs every day.

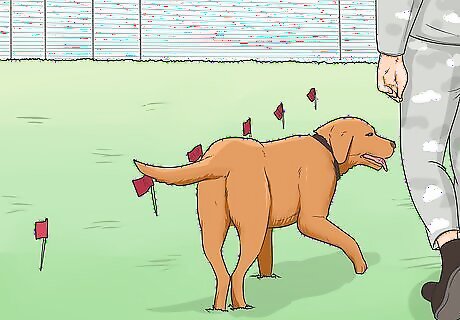

Schedule consistent training sessions in a low-distraction location. Military trainers may not use rigid timetables for success, but they do use predictable training schedules. Choose 1 or 2 specific times each day for training, and hold training sessions in the same location each time. Look for a low-distraction training location, like an enclosed backyard or an isolated corner of the park. One of the reasons why dogs tend to make great “soldiers” is that they usually thrive on predictable schedules. Holding the training session at the same time each day helps your dog slip into “training mode” more easily. Military dogs typically train for at least 4 hours per week and at least 30 minutes per day. Aim for 1 30-minute or 2 15-minute sessions per day, 6-7 days a week.

Rely entirely on positive reinforcement to instruct the dog. Positive reinforcement is the preferred method for all types of dog training, military-style or otherwise. At its core, it means immediately identifying, praising, and rewarding positive behaviors and identifying but not punishing negative behaviors. For instance, while house-training a dog, positive reinforcement means immediately responding anytime the dog “goes potty” properly with specific praise—”Good job, Scout, you went potty outside!”—and possibly a physical reward like a toy or treat. However, when the dog has a potty accident inside, positive reinforcement means you simply and immediately identify the problem—“Scout, you went potty inside!”—and clean up the mess. It never involves hitting the dog or sticking its nose in the mess.

Teach instructional commands like “sit” with clear verbal and hand cues. Like military dog handlers (and most dog trainers of all types), start with 1 of the basic instructional commands—such as “sit,” “down,” “heel,” or “stay”—and master a single command at a time. Speak the command clearly and provide a distinct visual cue (such as a hand motion) at the same time. Provide subtle guidance as needed—such as nudging, but never forcefully pushing, the dog into a seated position. Don’t shout the commands or show anger or displeasure when the dog doesn’t comply properly. Remember to keep your cool and stay positive. The instructional commands you teach beyond the basics like “sit,” “down,” “heel,” and “stay” depend upon your needs and the dog’s abilities. Military dogs may learn commands for things like detecting explosives or subduing enemies that you won’t need to teach, but the instructional methods remain largely the same.

Reward success immediately, consistently, and reasonably. It’s critical that you give praise and rewards the instant the dog responds properly, especially early in the training process. Give verbal praise and a physical reward like a pat on the head, a tug at a chew toy, or a small treat. If you use treats for rewards, keep them small. Otherwise, your dog may consume far too many calories. Military trainers don’t use treats as rewards beyond the very beginning of training, if at all. Their goal is to turn a basic verbal reward—often a simple phrase like “yes”—into the thing that the dog craves. Verbal-only rewards are, after all, much more practical in military situations.

Teach the dog not to do things by ignoring—not punishing—the dog. For instance, if the dog tends to jump up on you as a greeting, don’t tell it “no” or give a command like “sit.” Instead, walk away to somewhere the dog cannot follow—ideally by closing a door so it can’t see you—and return after around 20 seconds. Repeat the process until the dog consistently learns what not to do, and reward it as normal for successes. Saying “no” or giving alternate commands will just confuse the dog and make it think the unwanted behavior (such as jumping) is part of the command. Punishing the dog through scolding or any type of physical abuse is completely unhelpful. Since you’re the “alpha,” the dog craves your attention and approval. Ignoring it briefly is a mild form of corrective “punishment” that the dog can understand and learn from.

Identify, adapt to, and work around the dog’s weaknesses. Military dogs are specialized canines—the U.S. military, for instance, runs its own breeding program and makes targeted purchases of primarily German Shepherds, Belgian Malinois, and Pit Bulls. Even so, only about 50% of the canines make the cut as Military Working Dogs (MWD). Your dog is even less likely to have this high level of training capability, so be realistic about what it can and cannot achieve. Potential MWDs may come up short in their capability to identify explosives or drugs, for instance. You likely aren’t going to do training in these areas, but you may find that your dog isn’t well-suited to something like obeying “heel” commands. Don’t give up completely in that area, but also be realistic and focus your training in other areas. EXPERT TIP Sheri Williams Sheri Williams Certified Dog Trainer Sheri Williams is a Certified Dog Trainer and Behaviorist and the Owner of sheriwilliams.com, a business that specializes in teaching veterans how to turn their dogs into service dogs or emotional support animals to assist with PTSD. Based in the Los Angeles, California metro area, Sheri has over 20 years of dog training experience and also runs a general dog training practice specializing in rehabilitating dogs through positive reinforcement training techniques. She is certified by The Animal Behavior and Training Association. Sheri Williams Sheri Williams Certified Dog Trainer Become an expert through in-person training. To become skilled at dog training, it's helpful to do an in-person training program rather than learning online. Real-life experience working directly with the dogs and trainers is invaluable for picking up the nuances of dog behavior and training techniques.

Reinforce existing training while adding new training. Dog training is an ongoing process, and it’s important to offer “refreshers” of prior training while also moving on to new commands and tasks. In other words, don’t completely stop instructing the “stay” command once your dog masters it. At the beginning of each training session, loop back and spend a couple of minutes reinforcing “stay” (and other mastered commands) before moving on to your current training. Old dogs can learn new tricks, and they can also forget old tricks!

Becoming a Military Dog Trainer

Enlist in the military, complete basic training, and serve on active duty. In the U.S. military at least, dog handlers and trainers are not civilian contractors or specialty recruits. Instead, they are enlisted, active-duty personnel who complete basic training, express an interest in taking on a dog-related role, and demonstrate the desired capabilities. The official job title in the U.S. military is Military Working Dog Handler (MWDH). The compensation packages and career advancement opportunities are similar to those in comparable fields within the military. National militaries across the globe train and utilize dogs in various capacities. Consult a military recruiter where you live for more information.

Take the ASVAB tests to confirm your suitability as a MWDH. You can’t just request to become a MWDH and be put into the program. Instead, you must first take a series of written tests called the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). These tests assess your skills, training, knowledge, and temperament. Based on your results, you may be approved for entry into the MWDH training program. The ASVAB is not specifically focused on dog training. Rather, it is a general aptitude test used widely by the U.S. military to help determine which service members are good candidates for particular fields. The ASVAB tests cover 10 general knowledge categories in multiple-choice format. For more information, visit https://www.goarmy.com/how-to-join/steps/asvab.html.

Complete the 7-week Phase 1 of Advanced Individual Training (AIT). If your ASVAB results confirm your suitability for an MWDH job and you’re assigned to the program, your training will start with Phase 1 of the 2-phase AIT. During Phase 1, the focus is on learning military techniques for both dog training and policing. This is primarily on-the-job training in which you’ll work alongside current MWDHs. The Military Working Dog (MWD) program for the entire U.S. Department of Defense (including all branches of the military) is headquartered at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas. There’s a good chance you’ll be stationed there for part if not all of your AIT.

Finish the 11-week Phase 2 of AIT with your assigned, experienced dog. During this phase you’ll be assigned a particular MWD and further develop your training and handling skills alongside it. Your assigned MWD will almost certainly be the more experienced member of the partnership, so keep in mind that you’ll need to learn from your canine companion! Phase 2 reinforces essential dog training and handling techniques while also getting into specifics like searches and “controlled aggression” (in other words, deploying the dog as a non-lethal asset).

Serve as a MWD trainer as part of your assigned roles. Once you pass AIT and become a MWDH, there are a wide range of jobs you may be assigned. You might do military policing, search for drugs or explosives, provide protection for government officials, serve in combat zones, or take on any number of other roles. No matter your task or tasks, however, training your assigned MWD is always a critical, daily component of your job. MWDHs spend time practically every day training their MWDs. This, combined with their on-duty time in their specified roles, means that they spend a significant portion of every day alongside their MWDs. It’s no surprise, then, that these human and canine service members often develop a deep bond that continues after one or both leave the service.

Comments

0 comment