views

Using Strategies to Help with Communication

Assume that all children are competent. All autistic children are capable of learning. They simply need to find a strategy for proper information absorption. If an autistic child is not learning, it is not because they cannot learn, but because there is some barrier. Too much noise in the environment, an untreated anxiety disorder, or bullying are examples of issues that can impede learning. Limited communication skills may also prevent them from demonstrating what they know. Learn to accept that autistic children may always have differences, and should not be evaluated on the same basis as their neurotypical classmates. Autistic children should be evaluated in relation to their own growth and learning over time Understand that not all autistic children can use the same techniques that you use when teaching a certain subject. Some autistic kids may pick it up very quickly. Autistic kids may have uneven skill profiles. Make sure that the material is appropriate (including supplying more advanced material as needed).

Recognize how autistic body language can be different. An autistic child isn't going to act like a non-autistic child, and that's okay. Many autistic differences are adaptive; the child acts this way for a reason. Instead of trying to teach them to suppress their natural body language and pretend to be non-autistic, accept their differences and focus on teaching skills that will be more helpful. Eye contact can be distracting or painful for autistic people. An autistic child may prefer to look at a different part of you or stare into space to help them listen better. Fidgeting is normal and helps with coping skills. Turning away is not a sign of rejection, but a sign of being overwhelmed. Movement disabilities may cause jerky, clumsy, or overly forceful movements. Facial expressions may look distant, odd, or exaggerated. This usually isn't on purpose. Autistic children may need extra processing time and thus respond more slowly.

Speak in clear, precise language. Some autistic children may struggle with sarcasm, idioms, puns, and jokes. When talking to them, be as precise and specific as possible. Say what you mean when you want them to do something. For example, instead of telling them "Perhaps you should go back to the drawing board," say, "I want you to try this activity again."

Avoid long verbal commands or lectures. These can be confusing, as autistic children often have trouble processing sequences, particularly spoken ones. Give them extra time to process what you say as some autistic children have problems processing what they hear. If the child can read, write down the instructions. If the child is still learning, written instructions with pictures might help. Give instructions in small steps, and use short sentences whenever possible.

Communicate with the child using functional aids if necessary. Some autistic children learn to communicate via sign language, pictures, or a voice output device. If the child uses any of these to communicate, learn the system so that you can effectively use it. For example, you may need to print out different pictures of food. At snack time, have the child point to what they want.

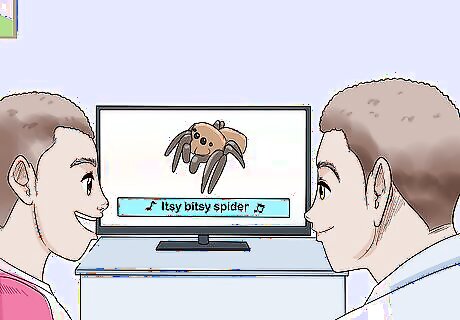

Use closed captions on a television. Autistic children sometimes struggle to process spoken words (especially from recordings due to odd acoustics), so seeing written words can help them understood what is being said. This can help both those who can and cannot yet read. Children who cannot read yet will associate printed words with spoken words. Children who can read may benefit from being able to see the words as well as hear them. If a child has a favorite television show, record the show with the closed captions and incorporate the show as part of the reading lesson.

Pay attention to what difficult behavior might be trying to communicate. Autistic people may struggle to express themselves in words, especially as children, so sometimes they may resort to "odd" or "bad" behavior to communicate a need or issue. Instead of writing it off as naughtiness or attention-seeking, search for the root of the problem. Passivity, delays, or noncompliance may mean that the child is dealing with a problem that they don't know how to verbalize. Sometimes autistic kids pretend to be an animal (such as a cat or dog) when they're stressed. Hissing or growling may be easier than finding the words for how they feel. If a child starts doing this, it might be a sign that they need help or a break.Did You Know? There are many potential reasons for "difficult" behavior. Overwhelm, sensory pain, nervousness or confusion about a task, frustration, anxiety, hunger, tiredness, and more can lead a child to act out or become passive (especially if they struggle to express themselves in words). Don't assume that they're misbehaving when they really might need someone to look closer and offer help.

Using Strategies to Help with Social and Behavioral Issues

Use special interests to facilitate the learning process. Many autistic children feel more engaged when their favorite things are incorporated in a lesson, and they tend to enjoy it more. Use their passion to your advantage when teaching. For example, if a child loves cars, use toy cars to teach geography on a map by "driving" the car to different states.

Teach autistic children through peer modeling. Many autistic children have difficulties being attuned to emotion, motivations, and other social cues that are instinctive among non-autistic children. They care about others' feelings, but don't always understand why people feel how they do. Explicitly and clearly explaining social nuances can be helpful as they can be confusing to many autistic children. Most autistic children are capable of learning social skills. They may simply need to be told techniques explicitly, instead of picking them up only through observation. Very young children in preschool and kindergarten can learn simple tasks like color discrimination, letter discrimination, or answering "yes" or "no" to simple questions by observing their peers engaging in these tasks. During centers or group work, consider pairing an autistic child who struggles in a certain area with a child who excels in that area. For instance, if an autistic student struggles with color discrimination, pair that child with a child who excels in color discrimination. By observing a peer perform the task correctly, an autistic child can learn to mimic the targeted behavior. Socially savvy kids can be trained to serve as peer models for their autistic classmates, modeling social skills for interaction such as pleasant greetings, sharing ideas, recommending changes nicely, giving compliments, and talking in a pleasant voice, among other things. Make sure that the child is interested and willing to help first. If peer modeling does not help, it may be a sign that there is an environmental or other barrier (e.g. a noisy environment, an unpredictable schedule, or an untreated anxiety disorder) that is hindering the autistic student's learning.

Read stories that teach emotional intelligence. For example, read a story about a child who is sad and point out a frown or tears as examples of sadness to help an autistic child learn how to pick up on emotions. The child can learn emotional and social skills from stories. You can use fictional stories to spark conversations like "What could Kelsey Bunny do when she feels mad?" or "What do you think might help cheer up Prince Jamal?" Some autistic children benefit from a technique known as "social stories", very brief narratives that describe social situations. These stories help them by providing behaviors to model in various situations.

Refuse to tolerate bullying. Autistic kids are at high risk for bullying victimization. Bullying can hinder the development of social skills and may teach the child to fear and mistrust people in general. Be firm if you notice one student mistreating the other. Take reports of bullying seriously and talk to the perpetrator about how this is unacceptable and why they are acting out. Never blame the victim. Comments like "you're being too sensitive" or "this wouldn't happen if you could stop fidgeting" can teach the child to be ashamed of themselves and to avoid seeking help in the future. Even if the autistic child is not the victim, they may pick up on the hostile behavior and become scared or confused. They may also think this behavior is acceptable when it is not.

Create a predictable schedule. Many autistic children thrive on a predictable schedule, so giving them the security to know what to expect each day is beneficial. If there is not enough structure autistic children may be overwhelmed. Place a clearly-visible analog clock on the wall and tape images that represent the day's activities and the times they occur. Refer to this clock while mentioning the time that activities are to take place. If the child has difficulty reading analog clocks (as a lot of autistic children do), invest in a digital clock that is equally visible. Picture schedules are also useful.

Talk to the student about good ways to handle difficult emotions. Autistic kids can have big emotions and they may not know how to deal with them. Having conversations about healthy ways to handle feelings can help the child later on. Stepping away to take some deep breaths Counting Fidgeting safely Using a calm-down room or asking the teacher for a break (verbally or nonverbally)

Show empathy to a student who is struggling to behave properly. Instead of assuming that they're choosing to be naughty, assume that something is upsetting them and preventing them from behaving the way they'd like. Maybe they need a sensory problem handled, a social situation handled, or just someone to help them express pent-up feelings. Try to help them label what they're feeling. This helps their emotional development and also helps you figure out what's upsetting them and causing them to act this way. Ask them what would help them feel better. Maybe they need you to fix a problem, or maybe they just want a little attention from you. Validate their feelings and show empathy. For example, "Yes, that must be upsetting that your sweater is so itchy. I know it's not easy to focus when you're uncomfortable. You're allowed to take it off so you can feel better."

Recognize the value of praise. Praise encourages good behavior and can help with self-esteem. Try to give the student at least as much praise as you give criticism or correction.

Using Strategies to Help with Sensory Issues

Delineate the teaching space. This is crucial as autistic children often have trouble coping with different environments or chaotic spaces. Construct your teaching area with separate and defined stations such as toys, crafts, and dress up. Have a calm and quiet space where the child can take breaks if they are overwhelmed. Place physical indications of defined areas on the floor, such as mats for each child to play upon, a taped square outline for a reading area, etc.

Reduce distracting or upsetting sensory input as much as possible. Unmet sensory needs can hinder self-control, attention, and learning. The more comfortable the environment, the better the child can focus on learning. Notice what bothers the child and see if you can minimize it. Think of uncontrolled sensory input as taking up a certain percentage of the brain. In a perfectly peaceful room, a child may have 100% of their brain and thus be clear-headed and mostly well-behaved. In a chaotic room, they may only have 70% or 50% of their brain, so their learning and behavior will suffer. You won't be able to control everything, but you can do your best to reduce distractions. The child's stimming (repetitive behaviors) may also help them "drown out" distractions so they can focus better.

Observe the child's self-created framework for learning. In some cases this will involve particular objects, behaviors, or rituals that support learning or memory. This can vary by child. Do they need to walk to list the alphabet? Does holding a blanket help them to read aloud? Whatever it may be, allow the children to learn within their own framework. Some autistic children use noise-cancelling headphones or weighted blankets to calm themselves down when they are overstimulated. Respect the child's need to use these tools.

Accept stimming. "Stimming" is a term that refers to self-stimulatory behavior such as flapping hands or fidgeting, frequently observed among autistic people. Stimming is crucial to autistic children's concentration and sense of well-being. An autistic child who fidgets may be more calm and attentive than an autistic child who sits perfectly still. Teach the child's peers to be respectful of stimming, rather than teaching the autistic child to suppress it. Occasionally, an autistic child will seek stimulation from biting, hitting, or otherwise harming themselves or others. This may be a sign of distress or boredom. In this case, it is best to speak with the special education coordinator to figure out how to help the child use a replacement stim that does not cause harm and/or fix what is bothering them. Avoid telling an autistic child not to stim. This can make them feel bad or ashamed of themselves.

Try making a few sensory tools available. Fidget toys can help autistic kids stim in safe and non-distracting ways, and some non-autistic kids may find them beneficial too. Consider putting a bin of sensory toys in your classroom to help kids regulate their attention. If a child is distracting others, remind them to think about other students' learning. Encourage them to use the item in a way that doesn't get in others students' way while they listen. If someone is clearly goofing off with an item, remind them that it's there to be a tool and not a toy. It's meant to help them learn, and they can either use it to help them or put it in the bin. Try to avoid taking items away, especially from a distressed-looking autistic student. Sometimes a fidget toy is the only thing that is keeping them from an emotional breakdown.

Recognize that there's a reason behind "odd" reactions to sensory input. Autistic people perceive the world differently and they react in ways that make sense to them. For example, if a child panics every time someone touches their head, it may be because it is disruptive or painful to them (many autistic individuals have a low pain threshold). You may want to explain to other class members that the autistic student is not reacting just to make others laugh, and that they do not like whatever the stimulus is. Autistic children are often bullied unintentionally, as neurotypical children can find their reactions amusing or annoying, and do not understand when something is negatively affecting an autistic student. If an autistic child is struggling to comply with instructions, don't assume it's willful misbehavior. Sensory issues or unmet needs may be making it difficult for them. Try to figure out what's wrong, and see if you can fix it.

Understanding the Law and Best Practices

Understand that every child has the right to an education, regardless of disability status. In the United States, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, enacted in 1975) and the Americans with Disabilities Act (enacted in 1990) are federal laws that require public schools to provide a free and accessible education for all individuals. The laws cover children who meet eligibility requirements in one of thirteen areas, whose disability negatively affects his or her educational performance, and who requires special educational services as a result of their disability. Autism spectrum disorder is a qualifying diagnosis. Not only must the state provide a free education for all individuals, but that education must meet their unique individual needs, which can differ from neurotypical children (that is, children who have no brain-related disabilities). Every child who qualifies for special education services must have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), which specifies what accommodations a student requires because of his or her diagnosis. Reasonable accommodations for a child receiving special educational services can vary widely. Some students may only need extra time to take tests or assistive technology like a laptop, while others may require a paraprofessional, small group instruction, or curriculum modification.

Respect your student's privacy through confidentiality. It is a teacher's responsibility to accommodate a student's IEP without singling out the child or disclosing his or her diagnosis to the rest of the class without permission. Students with special needs often have medical diagnoses, treatment plans, and medications included in their educational records, which are all protected under their right to privacy under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. This makes you legally liable if you disclose their private information without the consent of their parents. Generally, the student's right to privacy is limited by a "need to know" basis. Faculty and staff (coaches, playground monitors, cafeteria staff, etc.) might need to know about an autistic child's condition in order to understand their communication skills, limitations, special interests, outbursts, or other aspects of their disability. If you are unsure about your district's confidentiality procedures, talk with the district special education coordinator. Consider arranging a topical workshop for teachers to learn about these procedures. If you need to initiate a class- or school-wide policy to protect the interests of a child with special needs (for instance, instituting a peanut-free policy at a school where a child is allergic), notify the families of the policy and indicate that it is to protect a student with a special need. However, do not mention the affected child by name. Autistic students and their classmates all benefit if the other students understand an autistic classmate's diagnosis, but for privacy reasons the teacher cannot disclose that diagnosis to the class. Many proactive parents will take it upon themselves to discuss their child's autism with the class; plan a meeting with the parents early in the school year to let them know that your classroom doors are open to them if they want to do this.

Support a "least restrictive environment." IDEA mandates that students with disabilities are entitled to the "least restrictive environment" in education, which means their learning environment should be as similar to their non-disabled peers as possible. The least restrictive environment for a given student will vary, and is determined and written into the IEP by a team of people including the parents, medical team, and the school district's special education department. The IEP will generally be re-evaluated annually, which means the least restrictive environment for a given student may change. In many cases, this means that autistic children should be educated in regular classrooms rather than in a special education classroom. This can vary depending on the student's diagnosis and IEP, but in general, autistic students are placed in regular classrooms as much as possible. This practice is called "mainstreaming" or "inclusion". In these situations, it is the responsibility of the teacher to make accommodations in the classroom for autistic children. Many of these accommodations will be specified on the student's IEP. But educated teachers can also adapt their teaching strategies in ways that will support the learning processes unique to autism, while simultaneously respecting the learning needs of the remaining neurotypical students.

Evaluate approaches and interventions on an individualized basis. In addition to a student's IEP, adaptations that are made for autistic students should be evaluated and implemented based on the individual student's needs. Get to know the student as an individual. While stereotypes are common, every autistic person is unique, and will have different needs. As a teacher, you must become aware of each student's ability in each discrete educational area by assessing their current standing. Knowing a student's current strengths and weaknesses will help you develop a plan to develop practical interventions. This is true in academic subject areas, as well as social and communication skills.

Comments

0 comment