views

Understanding Them

Don't assume that someone has an intellectual disability based on the ease of their speech. Some people who have difficulty speaking, such as people with cerebral palsy and some autistic people, are on average just as smart as anyone else. A disability accent, slow speech, or halting speech doesn't always mean an intellectual disability. People who can't speak can be of any intelligence level. Body language does not relate to intelligence either. Looking away while listening, and fidgeting constantly, are typical autistic traits. Don't assume that this means they aren't paying close attention, or that they can't understand.

Recognize that ability varies from day to day. Someone who needs little help today might need more help tomorrow. Stress, sensory overload, lack of sleep, how hard they pushed themselves earlier, and other factors can determine how easy it is for someone to communicate and perform other tasks. If they are having a harder time today than they did yesterday, remember that they aren't doing this on purpose, and work on being patient.

Ask questions if you don't understand what they're saying. They may word things in unusual ways. If they have a speech impediment or a soft voice, it may also be hard to catch the words they say. Instead, ask them questions to clarify what they're trying to say. For example, if your friend asks "Where's the thing?" then ask questions about what type of thing they mean (a little thing? what color? a cell phone?). Sometimes, they might be searching for a word. For example, if they're asking about food, and there are many types of food, then start narrowing it down. Maybe they're saying "food" when they want to ask about strawberries.

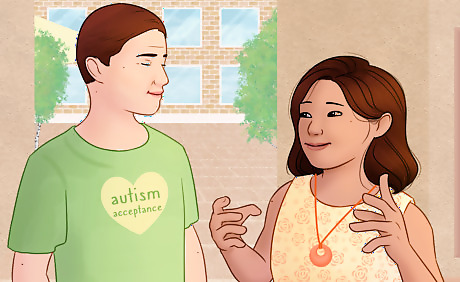

If you don't know, ask. It's absolutely okay to ask "How can I help you?" or "What would you like me to know about your disability?" Most people would rather have you ask them than assume who they are or what they need. As long as you're well-meaning and respectful, it'll be fine. If you want to know how to handle a specific situation, ask them. For example, "I notice that sometimes when we meet new people, they have a hard time understanding you, and you can be left out. How do you want me to handle this?"

Don't give up on understanding them. When speaking to a person who has difficulty speaking, some people ask "what did you say?" once and then let their eyes glaze over and pretend to listen. The person can usually tell when you aren't paying attention. Keep trying to connect. Make it clear that what they have to say is important to you. A useful phrase is "I'm having trouble understanding you, but I care about what you're saying." If verbal communication is too hard, try texting, typing on a tablet, writing, using sign language (if you know it), or another form of alternative communication. Work with them to figure out what is best.Did You Know? Some teens and adults with intellectual disabilities and speech impediments can spell out words they try to say. If you can't understand a specific word even when they repeat it, you can try asking them to spell it. They may be able to recite the letters so you can find out what they want to say.

Find conversation topics that interest them. Ask about their day, their favorite book or TV show, their interests, their pets, or their family and friends. This will help you get to know them, and you might make a new friend!

Being Polite and Respectful

Talk directly to the person instead of talking about them with someone else. The person may be with a family member, friend, teacher, or other person. Talking about someone like they aren't in the room is rude, regardless of whether the person has a disability. It makes them feel invisible. While it may take them longer to respond, it's worth including them. For example, instead of saying "I bet she likes ice cream," say "I bet you like ice cream."

Be age-appropriate. A disabled adult is still an adult and a disabled teenager is still a teenager. It's rude to treat them like a small child if they aren't one. It can be incredibly frustrating if it feels like nobody lets you grow up. Even if the person is childish in some ways, talk to them the same way you'd talk to another person their age. It shows that you respect them and their abilities. Save the baby talk for actual babies. Don't scold them for doing things like swearing or watching scary movies if you allow their same-age peers to do those things without commenting on it.

Don't lie to them, even for "nice" reasons. Sometimes people feel tempted to say untrue things like "you're the smartest ever" or "you're the best singer in the whole world" to people with intellectual disabilities. But that's not honest. Especially as they reach adulthood, they need a measure of realism to interact with the world. You can be kind without tricking them or giving them unrealistic expectations. You can support their skills without lying. For example, you could say "I love seeing the way you smile when you sing" or "your drawing is so colorful!" Save the baby talk for actual babies.

Ask if they want help before jumping in to help them. Sometimes they might not need help or they want to do it themselves. It's also possible you might be misunderstanding what they are trying to do. If you think they might need help, ask "Would you like help with that?"

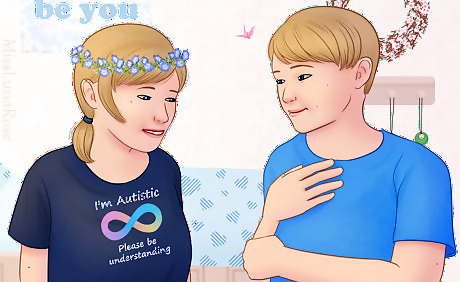

Accept their quirks. Disabled people may do things that society considers unusual: making sounds, flopping to the ground when frustrated, flapping their hands, running in circles, echoing phrases, pacing constantly, and more. This behavior serves a purpose—calming themselves down, communicating their needs, expressing feelings, or simply having fun. Recognize that it's okay to be different, and that there's no need to worry about behavior that doesn't hurt anyone. Don't try to stop them from doing harmless-but-odd things. These things may be crucial for them to stay calm and relate to the world. If they are causing harm (like hurting someone or invading personal space), nicely ask them to do something different, like "I don't want people playing with my hair. Could you play with your own hair instead?"

Being Clear

Speak calmly, clearly, and with a moderate volume. Enunciate well, and focus on clarity. Speaking louder doesn't make you more understandable. Consider this an opportunity to work on your clarity of speech.

Match their vocabulary. If they say the word "gigantic," then they probably also know what "enormous" and "huge" mean. If they speak using basic words, then it's probably best to use the smallest words you know. If they use words like "fortuitously" and "systematic bias," then their disability probably isn't intellectual.

Keep your sentences short and clear, if needed. If the person seems to struggle understanding speech, keep your sentences short and clear. Use simple subject-verb-object statements when you can. This is good practice in general too. Non-disabled people don't enjoy wading through extremely long sentences either. If you catch yourself rambling or losing them, stop. Try to summarize the main point of what you mean.

Let them see your mouth if they can't understand you well. If the person is hard of hearing or struggles to process speech, they may want to watch you as you pronounce your words. This helps them figure out what you are saying in many cases. Avoid turning away as you speak, covering your mouth, or speaking with your mouth full. It can also be helpful to talk in quieter places, with fewer distractions, especially if the person seems bothered by environmental noises.

Avoid running words together if it confuses them. For example, the question "Do-ya wanna eat-a pizza?" may be difficult for them to understand. One of the biggest challenges for listeners is knowing where one word ends and the next one begins. If they seem to be struggling, slow down the pace a little, giving a slight pause between each word.

Use your normal pitch and tone. There's no need to use baby talk, or mimic their speech impediment. (No, it won't help them understand you better, but it may make them think you're mocking them.) Talk to them with the same tone that you'd use for a non-disabled person their age. Baby talk may be appropriate for a disabled 3-year-old, but not a disabled 13-year-old or 33-year-old. Don't fake an excited or cheerful voice if that's not actually how you feel. Not everyone appreciates "the voice" because it can make them feel like they're being babied.

Being Friendly and Accommodating

Let the pace slow down as needed. If their speech is halting or labored, it may take them more time to get through a sentence. Give them utter patience, and don't rush them to finish what they're saying. This takes the pressure off and makes them feel more at ease.

Use open body language. Show them that you're interested in what they're saying by looking at them, and making eye contact if they're comfortable with it. Remember that they may have different listening body language than you do. If you aren't sure whether they're paying attention, watch to see if they react to what you say (e.g. giggling when you compliment them, asking questions) or just ask them.

Take time to listen closely to them. Sometimes, people with disabilities get sidelined and ignored, even with friends or family. This can be very isolating. Make time to include and listen to them, so they know someone cares about what they have to say. Ask questions about what they think, and take time to listen to what they say, even if you have to ask them to repeat themselves. Validate their feelings to help them feel cared about and understood.

Speak clearly and calmly to them if they're doing something that bothers you. Due to social uncertainty, past mistreatment, or anxiety issues, some disabled people may feel scared and confused if you are angry or hostile towards them. If you're getting very upset, take some deep breaths and try saying "I need some alone time" so you can handle your emotions privately. If the disabled person does something that upsets you, communicate it calmly and clearly. Try using "I" language in the template "When you ______, I feel _____" or "Please stop ____." Take some quiet time. If you need to speak to them to address the issue, wait until you are able to handle it with a level head. They won't be able to listen well if they are scared or confused by your strong emotions.

Be patient. They are facing barriers beyond your comprehension, and that can make conversation difficult. It's harder for them than it is for you. Never yell at a disabled person, or blame them for their disability. If you find yourself feeling too frustrated, disengage. Go for a walk, do something else, or say "I need some alone time for a little while."

Accommodate their needs. If you notice that they seem distressed, ask them "Is something wrong?" and "Is there anything I can do to help?" For example, a disabled person might feel distracted by all the movement in a crowded restaurant, and prefer to eat at an outdoor table where there are less people. People can talk much better when their needs are being met.

Remember that disabled people are still people. They have goals, interests, friends, (maybe) romantic relationships, boundaries, and preferences. They're regular people. Even if they look or act a little different, they're similar to you and other people in many ways.

Look for what you have in common with them. Ask about their interests and favorite activities, and look for similarities to what you like. You may share more favorite things than you think!

Comments

0 comment