views

X

Research source

Recognizing the Symptoms in Adults and Children

Watch for a severe headache. Headaches caused by inflammation of the meninges, the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord, feel different from other types of headaches. They're much more severe than a headache you'd get from dehydration or even a migraine. A persistent, severe headache is commonly felt by people with meningitis. A meningitis headache won't ease up after taking over the counter pain pills. If a severe headache is felt without the presence of other common meningitis symptoms, the cause of the headache may be another illness. If the headache persists for more than a day or so, see a doctor.

Look for vomiting and nausea associated with the headache. Migraines often lead to vomiting and nausea, so these symptoms don't automatically point to meningitis. However, it's important to pay close attention to other symptoms if you or the person you're concerned about is feeling sick enough to vomit.

Check for a fever. A high fever, along with these other symptoms, could indicate that the problem is meningitis, rather than the flu or strep throat. Take the temperature of the person who is sick to determine whether a high fever is on the list of symptoms. The fever related to meningitis is generally around 101 degrees, and any fever over 103 Fahrenheit is cause for concern.

Determine whether the neck is stiff and sore. This is a very common symptom among those who have meningitis. The stiffness and soreness is caused by pressure from the inflamed meninges. If you or someone you know has a sore neck that doesn't seem to be related to other common causes of soreness and stiffness, like pulling a muscle or getting whiplash, meningitis might be the culprit. If this symptom arises, have the person lie flat on his back and ask him to bend or flex his hips. When they do this, it should cause pain in the neck. This is a sign of meningitis.

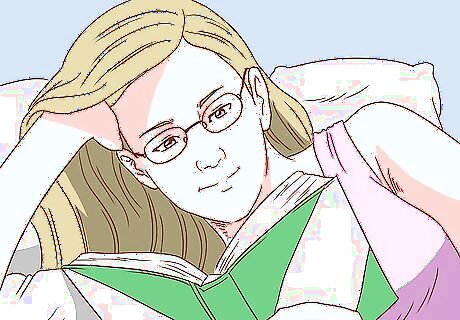

Watch for concentration difficulties. Since the membranes around the brain become inflamed with meningitis, cognitive difficulties commonly occur among meningitis patients. The inability to finish reading an article, focus on a conversation, or complete a task, paired with a severe headache, could be a warning sign. He may not act himself and be overall more drowsy and lethargic than usual. In rare cases, this can make the person anywhere from barely rousable to comatose.

Notice photophobia. Photophobia is an intense pain caused by light. Eye pain and eye sensitivity are associated with meningitis in adults. If you or someone you know has trouble going outside or being in a room with bright lights, see your doctor. This may manifest by a general sensitivity or fear of bright lights at first. Watch for this behavior if other symptoms occur as well.

Look for seizures. Seizures are uncontrollable muscle movements, often violent in nature, which usually cause loss of bladder control and general disorientation. The person who underwent a seizure likely may not know what year it is, where they are, or how old they are right after the seizure is over. If the person has epilepsy or a history of seizures, they may not be a symptom of meningitis. If you encounter someone having a seizure, call 911. Roll them on their side and move any objects that he may hit themselves on away from the area. Most seizures stop on their own within one to two minutes.

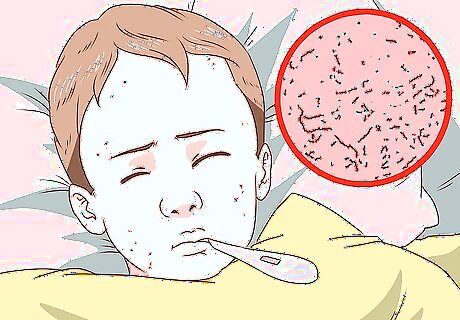

Look for the tell-tale rash. Certain types of meningitis, such as meningococcal meningitis, cause a rash to occur. The rash is reddish or purple and blotchy, and may be a sign of blood poisoning. If you see a rash, you can determine whether it was caused by meningitis by conducting the glass test: Press a glass against the rash. Use a clear glass so you can see the skin through it. If the skin under the glass does not turn white, this indicates that blood poisoning may have occurred. Go to the hospital immediately. Not all types of meningitis have a rash. The absence of a rash should not be taken as a sign that a person does not have meningitis.

Watching for Signs of Meningitis in Infants

Be aware of the challenges. The diagnosis of meningitis in children, especially infants, is a diagnostic challenge, even to experienced pediatricians. Since so many benign and self-limited viral syndromes present similarly, with fever and a crying child, it can be hard to distinguish meningitis symptoms in small children and infants. This leads many hospital protocols and individual clinicians to have a very high suspicion for meningitis, especially for those children 3 months and younger who have only received one set in their series of vaccines. With good vaccination compliance, the number of cases of bacterial meningitis have decreased. Viral meningitis still presents but presentation is mild and self-limited, with minimal care needed.

Check for a high fever. Infants, like adults and children, develop a high fever with meningitis. Check your baby's temperature to determine if a fever is present. Whether or not meningitis is the cause, you should take your baby to the doctor if he or she has a fever.

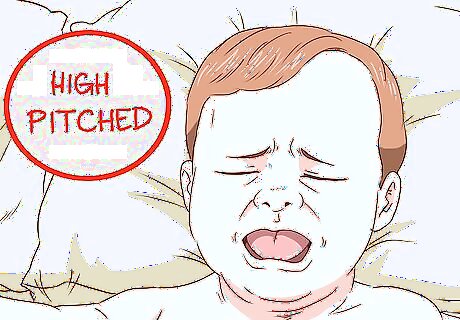

Watch for constant crying. This can be caused by many illnesses and other issues, but if your baby seems especially upset and won't be calmed by changing, feeding, and other measures you usually take, you should call the doctor. In combination with other symptoms, constant crying may be a sign of meningitis. Crying caused by meningitis usually can't be comforted. Look for differences in the baby's normal crying patterns. Some parents report that babies become even more upset when they are picked up if meningitis is the issue. Meningitis may cause babies to produce a cry that is higher-pitched than normal.

Look for sleepiness and inactivity. A sluggish, sleepy, irritable baby who is usually active may have meningitis. Look for noticeable behavioral differences that point to lower consciousness and an inability to fully wake up.

Pay attention to weak sucking during feedings. Babies with meningitis have a reduced ability to make the sucking motion during feeding. If your baby is having trouble sucking, call the doctor immediately.

Watch for changes in the baby's neck and body. If the baby seems to have trouble moving his or her head, and his or her body looks unusually rigid and stiff, this could be a sign of meningitis. The child may also feel pain around their neck and back. It may be simple stiffness at first, but if the child seems in pain when moved, it may be more severe. Watch to see if she automatically brings her feet up to her chest when you bend their neck forward or is she has pain when her legs are bent. She may also be unable to straighten her lower legs if her hips are at a 90 degree angle. This presents in infants most often when their diapers are changed and you cannot pull their legs out.

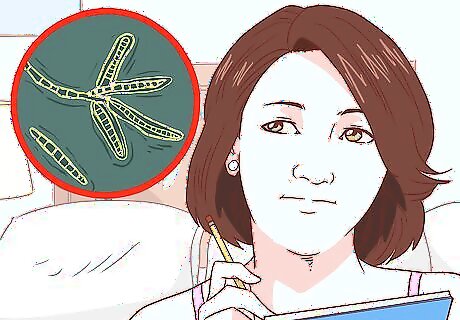

Understanding the Different Types

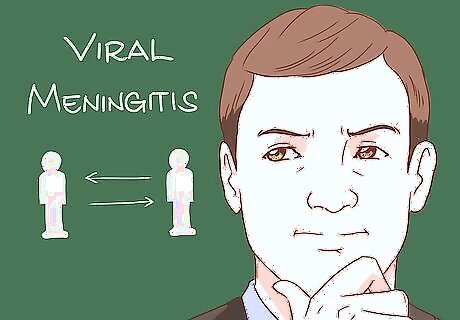

Learn about viral meningitis. Viral meningitis is usually self limited and goes away on its own. There are a few specific viruses such as the herpes simplex virus (HSV) and HIV that require specific goal directed therapy with antiviral drugs. Viral meningitis is spread person to person contact. A groups of viruses called enterovirus is the primary source and occur most typically in the late summer to early fall. Despite it being possible to be spread by person to person contact, outbreaks of viral meningitis are rare.

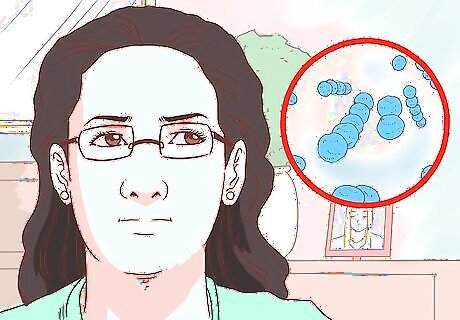

Know about Streptococcus pneumoniae. There are three kinds of bacteria that cause bacterial meningitis, which is the most worrisome and lethal. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common form to strike infants, young children, and adults in the US. There is a vaccine for this bacteria, however, so it is curable. It is spread most commonly from a sinus or ear infection and should be suspected when a person with a prior sinus or ear infection develops symptoms of meningitis. Certain people are at higher risk, such as those who do not have spleens and those who are older. Vaccination for these individuals is protocol.

Understand Neisseria meningitidis. Another bacteria that causes bacterial meningitis is Neisseria meningitidis. This is a highly contagious form that afflicts otherwise healthy adolescents and young adults. It is spread person to person and outbreaks occur in schools or dorms. It is particularly lethal, leading to multi-organ failure, brain damage, and death if not rapidly identified and started on intravenous antibiotics. It also has the distinction of causing a “petechial” rash, meaning a rash that looks like lots of tiny bruises, and this is an important distinction to note. Vaccination is recommended for all adolescents 11 to 12 years of age, with a booster at age 16. If no prior vaccine was given and the patient is 16, only one vaccination is required.

Learn about Haemophilus influenza (Hib). The third bacteria that causes bacterial meningitis is Haemophilus influenza. This used to be a very common cause of bacterial meningitis in infants and children. However, since a Hib vaccination protocol has been introduced, rates have dropped dramatically. With the combination of immigrants from other countries that don’t follow routine vaccination or even parents who do not believe in vaccination, not all are protected against this form. Obtaining an accurate vaccination history, preferably from the actual medical record or yellow vaccine card, is critical when this, or any, form of meningitis is considered.

Know about fungal meningitis. Fungal meningitis is rare and seen almost exclusively in those with AIDS or others with weakened immune systems. It is one of the AIDS defining diagnoses, occurring when the person has very little immunity, is exceedingly fragile, and is at risk for most any infection. The typical culprit is Cryptococcus. The optimal prevention in an HIV infected individual is compliance with antiretroviral therapy to keep viral loads low and T cells high to protect from this type of infection.

Take advantage of meningitis vaccines if necessary. It is recommended that the following groups with high risk of contracting meningitis have routine vaccinations: All children ages 11-18 U.S. military recruits Anyone who has a damaged spleen or whose spleen has been removed College freshmen living in dormitories Microbiologists exposed to meningococcal bacteria Anyone who has terminal complement component deficiency (an immune system disorder) Anyone traveling to countries which have an outbreak of meningococcal disease Those who might have been exposed to meningitis during an outbreak

Comments

0 comment