views

Becoming Familiar with the Story

Read the script. Before you start marking up your script, it is a good idea to read through it once and just get a basic understanding of the story. You can read with a pencil in hand and make some general notes in the margins if you like. For example, you can mark lines that are confusing, surprising, important, or just interesting. You can also look for scenes or lines that are repeated or that seem to connect to other scenes or lines.

Cross out stage directions for plays. If you are acting in a stage production, then it is a good idea to put an X through any stage directions included in your script. The director of the production you are working on will probably design his or her own stage directions, so you will probably not need these. If you want to be sure, you can always ask the director if he or she will be following the scripted stage directions before you cross them out.

Look up unfamiliar words and concepts. There may be times when a word or concept in a script is unfamiliar to you. If this happens, make sure that you look it up. It is important to be fully aware of what your character’s lines mean. You can define unfamiliar words or concepts in the margins of your script or keep a log of them in a journal. You might have to look up lots of words and concepts if you are working with an old script, such as a play by Shakespeare.

Write down your questions. You may not be able to figure out everything on your own. As you read your script, another way to annotate it is to write down your questions. Then, you can bring up these questions during rehearsal. For example, if you encounter an unfamiliar concept and you don’t quite understand what it means after looking it up and reading about it, then you could include a question about it.

Read the script again. It is important to read the script multiple times to gain a good understanding of it and to do a thorough annotation. Make sure that you give yourself plenty of time to read through the script at least twice before you start memorizing your lines.

Deciding How to Deliver Your Lines

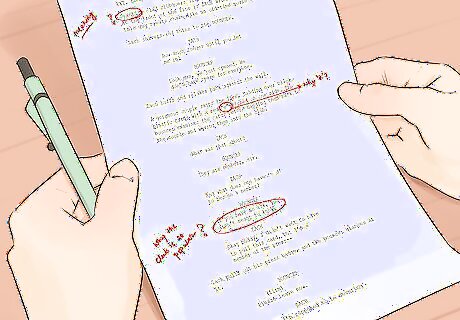

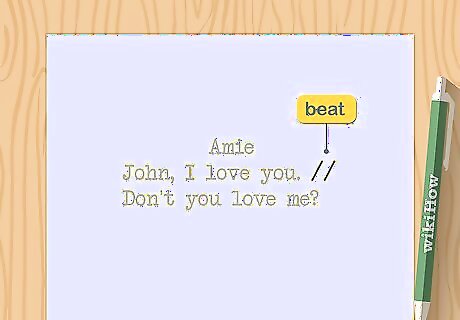

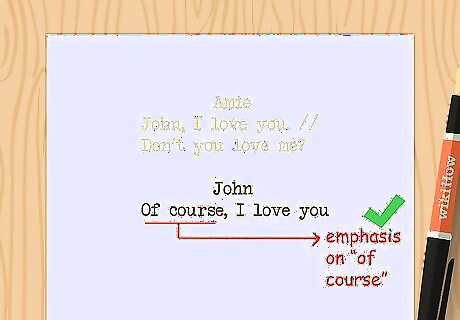

Identify beats with two slashes (//). A beat in a script is when something shifts, either in the script’s tone or in a character’s development. Identifying beats can help you to see when you need to alter the way that you deliver your lines from one sentence to the next. Mark beats with two slashes (//) to help you identify these crucial moments in your script. For example, you might identify a beat in the following lines: “John, I love you. // Don’t you love me?’’ In this situation, the character speaking the lines might be going from feeling love and affection, to being afraid that John does not feel the same way about her.

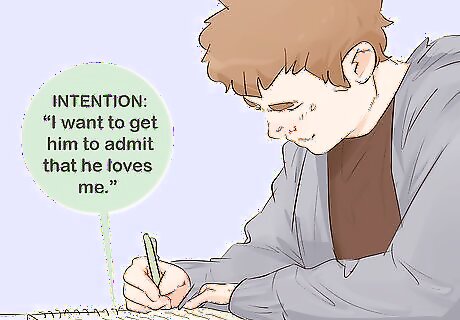

Note intention. It is important for actors to get inside of their characters’ heads and figure out what makes them tick. Intention is what is driving a character’s actions and words. Write your character’s intention for a scene at the top of the page where the scene begins. For example, the intention might be “I want to get him to admit that he loves me.” Or, “I want to convince my friend that he should not seek revenge.”

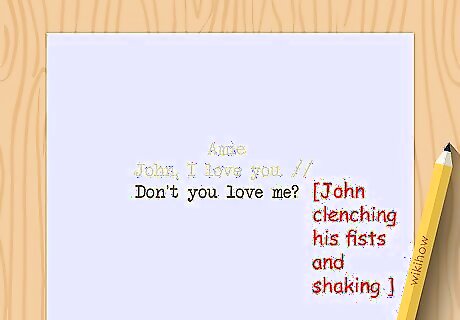

Clarify action in parentheses. Through rehearsals and becoming more familiar with your character, you will start to develop actions to go along with your lines and other character’s lines as well. Writing these actions in the margins can help you to link them with the lines. For example, you might decide that your character would reach out and grab John’s arm while your character asks him, “Don’t you love me?” Or, you might decide that your character would be clenching his fists and shaking while another character is yelling at him.

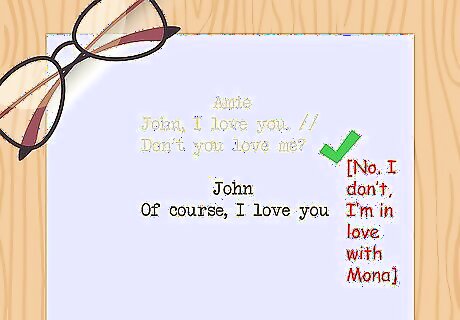

Consider subtext. Subtext is what your character is thinking and this might be quite different from what your character actually says. Noting your character’s subtext can help you to decide how to deliver certain lines. For example, if your character says, “Of course, I love you,” but the subtext is that he is in love with someone else, then you might say the line in a somber way or say the line while looking in the other person’s direction.

Emphasize important words and phrases. As you read through a script, make sure that you underline any important words or phrases that you think you will need to emphasize. These words and phrases may seem insignificant to a casual reader, but you may identify them as important based on what you know about your character. For example, in the line, “Of course, I love you,” you might decide to place the emphasis on “love” or “of course.” Delivering the line with emphasis on “love” might make it seem like the character is being defiant while delivering it with emphasis on “of course” could make it seem like the character is being sincere. Experiment with different types of emphasis to figure out what best expresses your character’s intention and subtext.

Adding Stage Directions

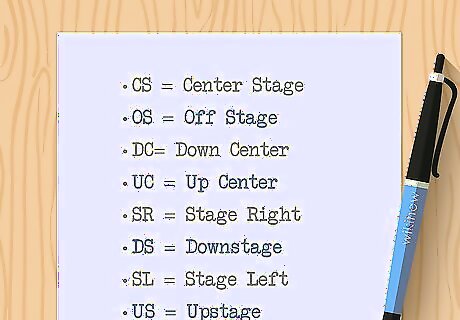

Learn abbreviations to note your stage locations. Annotating your script with your director's blocking instructions can make it easier to remember where you are supposed to be and what you are supposed to be doing during the performance. Some common abbreviations for blocking include: CS = Center Stage OS = Off Stage DC= Down Center UC = Up Center SR = Stage Right DS = Downstage SL = Stage Left US = Upstage

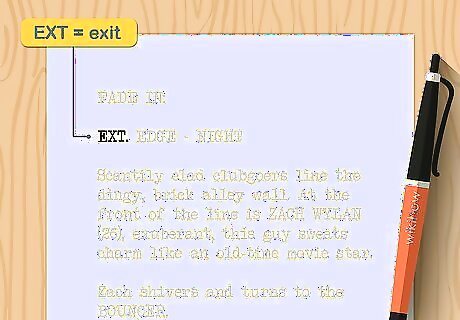

Note when to enter and exit the stage. Knowing when and where to enter and exit the stage is important. Your character might need to enter before her lines begin or exit a while after he or she has finished speaking. Note when to enter and exit the stage in the margins of your script by using abbreviations. ENT or Ntr = enter EXT or Xit = exit You can combine the abbreviations for entering and exiting the stage with other abbreviations to help you remember where to enter and exit. For example, you could indicate that you need to exist stage left by writing EXTSL in the margins of your script, or indicate that you need to enter stage right by writing NtrSR.

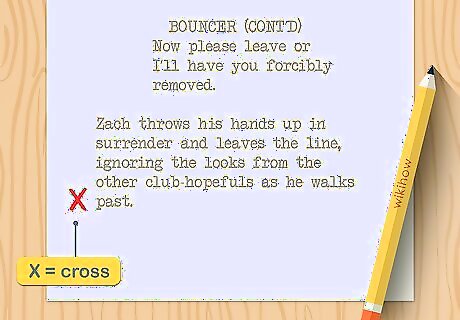

Identify when to cross the stage. Knowing when to move to a different part of the stage is also important. You can mark these instructions in the margins of your script using abbreviations as well. X = cross You can combine the cross abbreviation with others to identify where to cross to in a scene. For example, you might write XSL to indicate that you need to cross to stage left, or XCS to indicate that you need to cross to center stage.

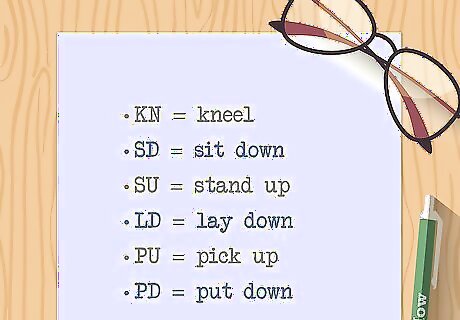

Use abbreviations for other actions and positioning. Your character might have to do other things, such as sitting, standing, kneeling, or picking up an object. You can abbreviate these actions in the margins of your script as well. Some abbreviations you might use to indicate different actions might include: KN = kneel SD = sit down SU = stand up LD = lay down PU = pick up PD = put down

Making the Most of Your Annotations

Use a pencil. When you annotate a script, it is a good idea to use a pencil rather than a pen. This is because you may develop new ideas as you familiarize yourself with the character and story. Using a pencil makes it easy to erase a note if you change your mind about it and write in a new one.

Review your annotations. After you have finished annotating your text, make sure that you review your annotations. Take time to read through all of them and make changes or additions to your annotations if you have developed new ideas about something. You can use what you have written to help guide your actions, tone, and gestures during rehearsals. For example, your notes on your character’s intention can help you to decide how to stand, how your face should look, and what tone to use when delivering your lines.

Ask questions. Your director and fellow actors can help you if you have unanswered questions or if you are struggling with something within the script. Bring up any unanswered questions that you have during rehearsals and listen to what your director and fellow actors have to say. By collaborating with others, you may gain an even deeper understanding of your character and use this knowledge to improve your performance.

Comments

0 comment