views

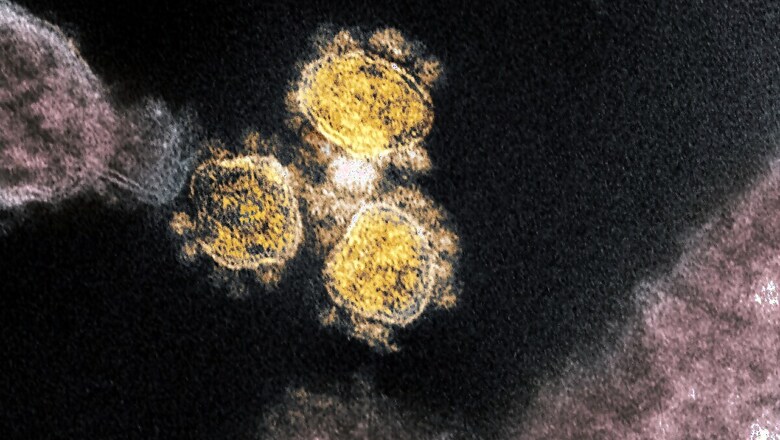

Scientists are beginning to untangle one of the most complex biological mysteries of the coronavirus pandemic: Why do some people get severely sick, whereas others quickly recover?

In certain patients, according to a flurry of recent studies, the virus appears to make the immune system go haywire.

Unable to marshal the right cells and molecules to fight off the invader, the bodies of the infected instead launch an entire arsenal of weapons — a misguided barrage that can wreak havoc on healthy tissues, experts said.

“We are seeing some crazy things coming up at various stages of infection,” said Akiko Iwasaki, an immunologist at Yale University who led one of the new studies.

Researchers studying these unusual responses are finding patterns that distinguish patients on the path to recovery from those who fare far worse. Insights gleaned from the data might help tailor treatments to individuals, easing symptoms or perhaps even vanquishing the virus before it has a chance to push the immune system too far.

“A lot of these data are telling us that we need to be acting pretty early in this process,” said John Wherry, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania who recently published a study of these telltale immune signatures. As more findings come out, researchers may be able to begin testing the idea that “we can change the trajectory of disease,” he said.

When a more familiar respiratory infection, like a flu virus, tries to gain a foothold in the body, the immune response launches a defense in two orchestrated acts. First, a cavalry of fast-acting fighters flocks to the site of infection and tries to corral the invader, buying the rest of the immune system time to mount a more tailored attack.

Much of the early response depends on signaling molecules called cytokines that are produced in response to a virus. Like microscopic alarms, cytokines can mobilize reinforcements from elsewhere in the body, triggering a round of inflammation.

Eventually, these cells and molecules leading the initial charge will stand down, making way for antibodies and T cells — specialized assassins built to home in on the virus and the cells it has infected.

But this coordinated handoff seems to break down in people with severe COVID-19.

Rather than bowing out gracefully, the cytokines that drive the first surge never stop sounding the alarm, even after antibodies and T cells arrive on the scene. That means the wildfire response of inflammation may never get snuffed out, even when it’s no longer needed.

“It’s normal to develop inflammation during a viral infection,” said Catherine Blish, a viral immunologist at Stanford University. “The problem comes when you can’t resolve it.”

This sustained signaling may result in part from the body’s inability to keep the virus in check, Iwasaki said. Many who struggle to recover from their illness seem to harbor the pathogen long after other patients have purged it, perhaps goading the immune system into prolonging its frantic inflammatory siege.

Plenty of other viruses, including those that cause AIDS and herpes, have evolved tricks to elude the immune system. Recent evidence hints that the new coronavirus might have a way of delaying or muffling interferon, one of the earliest cytokine defenses the body mounts.

The failure of this first line of defense may dupe the immune system into sounding its alarm bells even louder, dragging out the response into something destructive. “It’s an enigma,” said Avery August, an immunologist at Cornell University. “You have this raging immune response, but the virus continues to replicate.”

And the quality of these cytokines may matter as much as the quantity. In a paper published last week in Nature Medicine, Iwasaki and her colleagues showed that patients with severe COVID-19 appear to be churning out signals that are better suited to subduing pathogens that aren’t viruses.

Although the delineations aren’t always clear-cut, the immune system’s responses to pathogens can be roughly grouped into three categories: type 1, which is directed against viruses and certain bacteria that infiltrate our cells; type 2, which fights parasites like worms that don’t invade cells; and type 3, which goes after fungi and bacteria that can survive outside cells. Each branch uses different cytokines to rouse different subsets of molecular fighters.

People with moderate cases of COVID-19 take what seems like the most sensible approach, concentrating on type 1 responses, Iwasaki’s team found. Patients struggling to recover, on the other hand, seem to be pouring an unusual number of resources into type 2 and type 3 responses, which is kind of “wacky,” Iwasaki said. “As far as we know, there is no parasite involved.”

It’s almost as if the immune system is struggling to “pick a lane,” Wherry said.

This disorientation also seems to extend into the realm of B cells and T cells — two types of immune fighters that usually need to stay in conversation to coordinate their attacks. Certain types of T cells, for instance, are crucial for coaxing B cells into manufacturing disease-fighting antibodies.

Last month, Wherry and his colleagues published a paper in Science finding that, in many patients with severe COVID-19, the virus had somehow driven a wedge between these two close-knit cellular communities. It’s too soon to tell for sure, but perhaps something about the coronavirus is preventing B and T cells from “talking to each other,” he said.

These studies suggest that treating bad cases of COVID-19 might require an immunological reset — drugs that could, in theory, restore the balance in the body and resurrect lines of communication between bamboozled cells. Such therapies could even be focused on specific subsets of patients whose bodies are responding bizarrely to the virus, Blish said: “the ones who have deranged cytokines from the beginning.”

But that’s easier said than done. “The challenge here is trying to blunt the response, without completely suppressing it, and getting the right types of responses,” August said. “It’s hard to fine-tune that.”

Timing is also crucial. Dose a patient too early with a drug that tempers immune signaling, and they may not respond strongly enough; give it too late, and the worst of the damage may have already been done. The same goes for treatments intended to shore up the initial immune response against the coronavirus, like interferon-based therapies, Blish said. These could stamp out the pathogen if given shortly after infection — or run roughshod over the body if administered after too long of a delay.

So far, treatments that block the effects of one cytokine at a time have yielded mixed or lackluster results — perhaps because researchers haven’t yet identified the right combinations of signals that drive disease, said Donna Farber, an immunologist at Columbia University.

Steroids like dexamethasone, on the other hand, are like “big hammers” that can curb the activity of multiple cytokines at once, Farber said. Early clinical trials have hinted at dexamethasone’s benefits against severe cases of the coronavirus, and more are underway. Such broad-acting treatments have their downsides. But, she added, “it seems that’s a good strategy, until we know more.”

Katherine J. Wu c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment