views

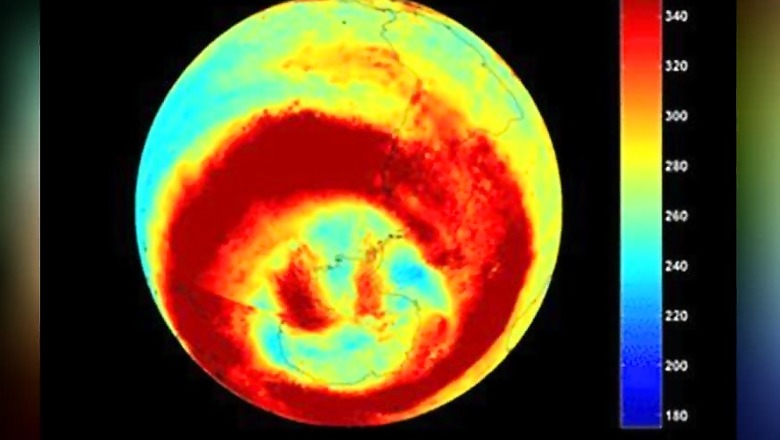

Geneva: The ozone layer - which protects life on Earth from high-energy radiation - has continued to thin over the last three decades, a study has warned.

In the 20th century, when excessive quantities of ozone-depleting chlorinated and brominated hydrocarbons such as CFCs were released into the atmosphere, the ozone layer in the stratosphere - ie at altitudes of 15 to 50 kilometres - thinned out globally.

The Montreal Protocol introduced a ban on these long-lasting substances in 1989.

At the turn of the millennium, the loss of stratospheric ozone seemed to have stopped. Until now, experts have expected that the global ozone layer would completely recover by the middle of the century.

However, a team led by researchers from ETH Zurich and the Physikalisch-Meteorologisches Observatorium Davos in Switzerland have found that despite the ban on CFCs, the concentration of ozone in the lower part of the stratosphere has continued to decline at latitudes between 60 degree South and 60 degree North.

The study, published in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, used satellite measurements spanning the last three decades together with advanced statistical methods.

Ozone is formed in the stratosphere, mainly at altitudes above 30 kilometres in the tropics. From there it is distributed around the globe by atmospheric circulation.

The scientists were somewhat surprised that the ozone is thinning out in the lower stratosphere because their models do not show this trend and CFCs continue to decline.

Certain aspects of their findings are not completely unexpected, however.

"Thanks to the Montreal Protocol, ozone in the upper stratosphere - ie above 30 kilometres - has increased significantly since 1998, and the stratosphere is also recovering above the polar regions," said William Ball, researcher at ETH Zurich.

Despite these increases, measurements show that the total ozone column in the atmosphere has remained constant, which experts took as a sign that ozone levels in the lower stratosphere must have declined.

The reasons for the continuing decline are still unclear. However, researchers have two possible ex-planations.

On the one hand, climate change is modifying the pattern of atmospheric circulation, moving air from the tropics faster and further in the polar direction, so that less ozone is formed.

On the other hand, very short-lived substances (VSLSs) containing chlorine and bromine are on the rise, and could increasingly enter the lower stratosphere, for example as a result of more intense thunderstorms.

Ozone-depleting VSLSs are partly of natural and partly of industrial origin; some are substitutes for CFCs, and although they are less ozone-depleting, they are not neutral either. "These short-lived substances could be an insufficiently considered factor in the models," said Ball.

"The decline now observed is far less pronounced than before the Montreal Protocol. The impact of the Protocol is undisputed, as evidenced by the trend reversal in the upper stratosphere and at the poles," said Thomas Peter, from ETH Zurich.

"But we have to keep an eye on the ozone layer and its function as a UV filter in the heavily populated mid-latitudes and tropics," he said.

Comments

0 comment