views

The moon is drifting away. Every year, it gets about an inch and a half farther from us. Hundreds of millions of years from now, our companion in the sky will be distant enough that there will be no more total solar eclipses.

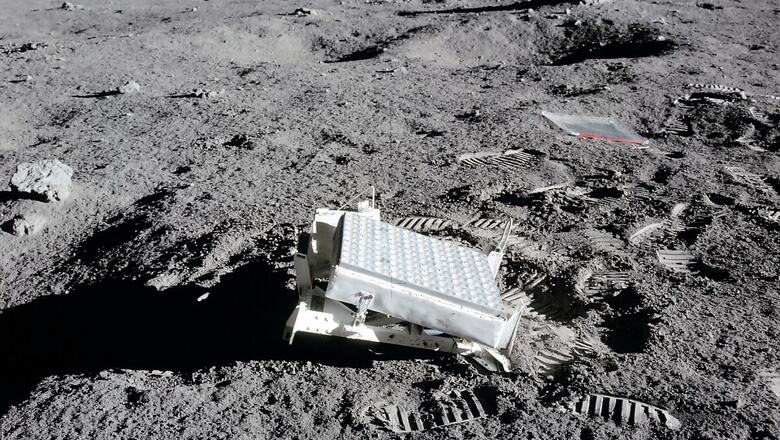

For decades, scientists have measured the moon’s retreat by firing a laser at light-reflecting panels, known as retroreflectors, that were left on the lunar surface, and then timing the light’s round trip. But the moon’s five retroreflectors are old, and they’re now much less efficient at flinging back light.

To determine whether a layer of moon dust might be the culprit, researchers devised an audacious plan: They bounced laser light off a much smaller but newer retroreflector mounted aboard a NASA spacecraft that was skimming over the moon’s surface at thousands of miles per hour. And it worked.

These results were published this month in the journal Earth, Planets and Space.

Of all the stuff humans have left on the moon, the five retroreflectors, which were delivered by Apollo astronauts and two Soviet robotic rovers, are among the most scientifically important. They’re akin to really long yardsticks: By precisely timing how long it takes laser light to travel to the moon, bounce off a retroreflector and return to Earth (roughly 2.5 seconds, give or take), scientists can calculate the distance between the moon and Earth.

Arrays of glass corner-cube prisms make this cosmic ricochet possible. These optical devices reflect incoming light back to exactly where it came from, ensuring that retroreflectors send photons on a tight, neat flip turn.

Making repeated measurements over time allows researchers to piece together a better picture of the moon’s orbit, its precise orientation in space and even its interior structure.

But the moon’s suitcase-size retroreflectors, delivered from 1969 through 1973, are showing their age. In some instances, they’re only about one-tenth as efficient as expected, said Tom Murphy, a physicist at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the research. “The returns are severely depressed.”

One obvious culprit is lunar dust that has built up on the retroreflectors. Dust can be kicked up by meteorites striking the moon’s surface. It coated the astronauts’ moon suits during their visits, and it is expected to be a significant problem if humans ever colonize the moon.

While it has been nearly 50 years since a retroreflector was placed on the moon’s surface, a NASA spacecraft launched in 2009 carries a retroreflector roughly the size of a paperback book. That spacecraft, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, circles the moon once every two hours, and it has beamed home millions of high-resolution images of the lunar surface.

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter “provides a pristine target,” said Erwan Mazarico, a planetary scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center who, along with his colleagues, tested the hypothesis that lunar dust might be affecting the moon’s retroreflectors.

But it’s also a moving target. The orbiter skims over the moon’s surface at 3,600 mph. “It’s hard enough to hit a stationary target,” said Murphy, who leads the Apache Point Observatory Lunar Laser-ranging Operation, or APOLLO, a project that uses the retroreflectors on the moon’s surface. “We’re going to give you a smaller array and make it move on you.”

In 2017, Mazarico and his collaborators began firing an infrared laser from a station near Grasse, France — about a half-hour drive from Cannes — toward the orbiter’s retroreflector. At roughly 3 a.m. on Sept. 4, 2018, they recorded their first success: a detection of 25 photons that made the round trip.

The researchers notched three more successes by the fall of 2019. After accounting for the smaller size of the orbiter’s retroreflector, Mazarico and his colleagues found that it often returned photons more efficiently than the Apollo retroreflectors.

There isn’t enough evidence yet to categorically blame the dust for the poorer performance of the moon’s retroreflectors, said Mazarico, and more observations are being collected. But Murphy and other scientists said the new findings were helping build the case.

“For me, the dusty reflector idea is more supported than refuted by these results,” he said.

Katherine Kornei c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment