views

In Rajpur village, just forty kilometers away from the city of Etawah, Uttar Pradesh, a group of farmers has a list of demands for the candidates who come here to solicit votes.

“This is irony,” says 70-year-old Virendra Dubey who turned to organic farming a few years ago, shunning the conventional method to grow crops. “While campaigning, all netas project themselves as farmers and sons of the soil, but they hardly care about our problems,” he laments.

Across the country when the crops fail year after year, farmers are pushed into a vicious cycle of debt. With the rising cost of fertilisers and pesticides, agriculture has become increasingly unsustainable for farmers. Input cost is soaring from 5 to 20 percent annually but the returns remain abysmally low.

So, Virendra Dubey is now encouraging his fellow farmers to use organic methods for agriculture.

“Three years back I said goodbye to costly pesticides and fertilisers and started using cow dung and compost to produce organic manure. This has reduced the cost of production by half,” he explains.

More than 20 families in this area of Chambal, close to Uttar Pradesh-Madhya Pradesh border, have started organic farming in the last few years and Saurabh Singh Chauhan, a young farmer of Gopalpur village, is among those who are spreading awareness about “no chemical farming”.

“As election comes, scores of candidates start flocking the village and make routine promises for road, electricity and water. But, we urgently need to get rid of the debt and costly agriculture. We know we have to find the solution ourselves. No one else will come to help us,” says Saurabh who grows wheat, mustard, pulses and vegetables in his land.

In February this year, central government announced PM Samman Nidhi direct income support to smallholder farmers. Under the scheme, annually Rs. 6,000 is transferred to the account of farmers in three installments. However, farmers in Gopalpura and Rajpur say such help should be provided to support a sustainable way of agriculture, not just as election sops.

As the peasant unrest grew in the last few years and they demonstrated and marched in different parts of country, News18 spoke to farmers in several states who are trying to switch to a safe and sustainable way of agriculture.

Far from Etawah, in the remote villages of Uttarakhand, 48-year-old Hem Pant has also engaged more than 50 families in organic farming. He started in 2003 and today he grows and collects organic produce from scores of villages in the hills.

“We process and package these products and sell them across North India. This is an effective way to help poor farmers. Now they get good price for their produce,” says Pant who runs a cooperative under the name Him Organic.

This farmer’s initiative in Bageshwar district of Uttarakhand has already crossed Rs 1.5 crore annual sale and it may cross Rs 5 crore business this year.

Last year, a report by ASSOCHAM said that the organic market is expanding in India and it will touch 12,000 crores by next year. Today, more than 8 lakh farmers are engaged in organic farming, yet the country’s total share is less than 1% of global organic business.

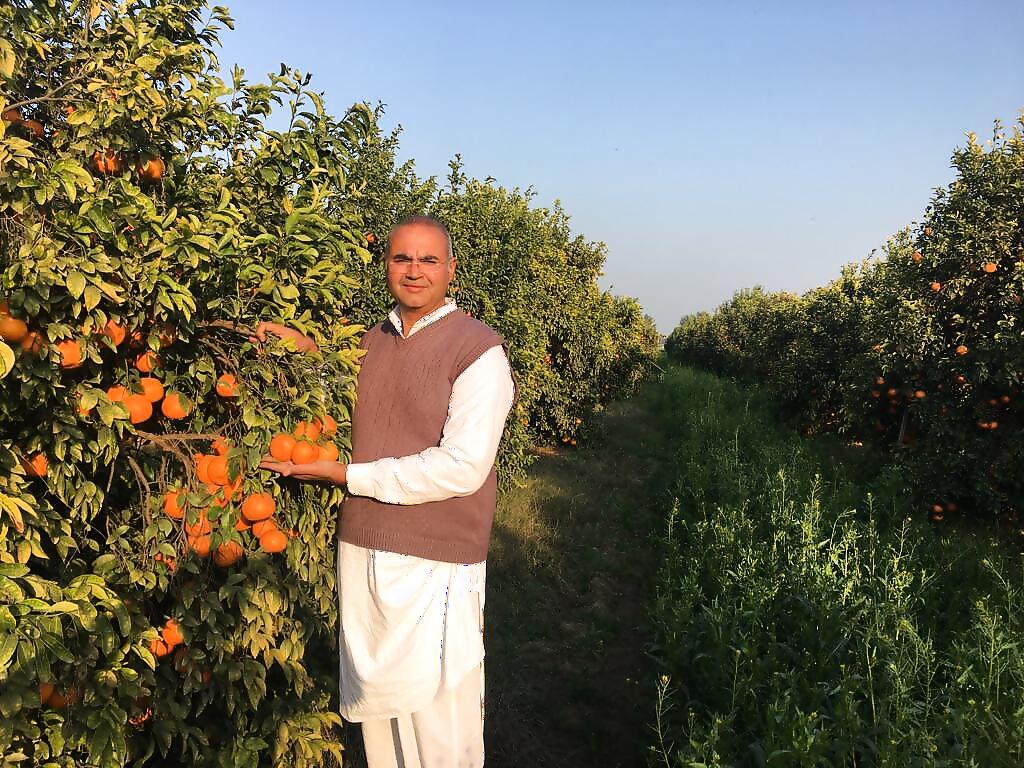

42-year-old Ramesh Bhadu takes us through his 56 acres of Kinnow farms.

Three hundred kilometre away from Delhi in Dhani-Sherawali village of Sirsa district of Haryana, 42-year-old Ramesh Bhadu takes us through his 56 acres of Kinnow (a citrus fruit) farms. Till a few years back, Bhadu would spend as much as Rs 7.5 lakh annually in fertilisers and pesticides but now the things are completely different.

“It is purely organic. I have reduced my cost of farming to one third, since I stopped using chemical fertilisers and pesticides,” says Bhadu who himself is associated with a political party but doesn’t expect netas to help farmers in their woes. “A farmer’s battle is purely his own,” he says laughingly.

But there are hiccups, as well. If the farmers are not educated enough about organic farming, they may get deterred by initial difficulties. The production of crop is less in first two years when one turns to organic and that is a challenge.

“I, too, had a little problem initially but now my profits are much higher and I am happy,” says Bhadu.

“Our politicians can and should learn a lot from these farmers and entrepreneurs. Even smallholder farmers are now understanding the hazards of conventional chemical-based farming and are turning to safe and sustainable way of agriculture,” says Jyoti Awasthi who has provided a platform to more than 100 farmers to sell their products in Delhi NCR under the brand name – Eat Right Basket. “We strive to be fair to both farmers and consumers. We continuously educate our buyers about the hardships farmers face to produce safe food and therefore they should be paid fairly,” adds Awasthi.

Comments

0 comment