views

Back in 1952, India became the first country in the world to have launched a National Programme for Family Planning. Over the decades, the programme has transformed in terms of its goals and repositioned itself to not only achieve population stabilisation but also promote reproductive health and reduce maternal, infant and child mortality and morbidity. The methods have shown a significant shift from traditional/natural rhythm practices to modern methods such as condoms, diaphragms, pills, injectables etc.

According to the World Family Planning 2020 report, the number of women desiring to use family planning has increased markedly over the past two decades, from 900 million in 2000 to nearly 1.1 billion in 2020. Consequently, the number of women using a modern contraceptive method increased from 663 million to 851 million, and the contraceptive prevalence rate increased from 47.7 to 49.0 per cent. An additional 70 million women are projected to be added by 2030. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicator 3.7.1, on contraceptive use by women of reproductive age (aged 15-49 years), has stagnated globally at around 77 per cent from 2015 to 2020.

Mismatch between Male and Female Sterilisation

Sterilisation as a mode of contraception is on the rise. The contraceptive choices in India are still governed by socio-economic indicators such as educational status, wealth, religion, caste, among many more. Studies indicate that the practice of sterilisation is common among women belonging to communities with poor economic and educational status. Islam does not favour permanent family planning methods for Muslim women compared to Hindu women, who tend to prefer sterilisation over temporary methods. In contrast, increased use of modern techniques like condoms and pills has been found among Indian women with higher socio-economic status, education and empowerment levels. Studies across India, Brazil, Bangladesh have found higher parity as determining factor for female sterilisation. But notably, it is still driven by son-preference at lower parities.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launched the ‘Mission Parivar Vikas’ in 2016 for improved access to contraceptives across 145 high-fertility districts in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Assam, Jharkhand. It was spearheaded with a focus on reversible, non-surgical and hormone-based contraceptives. In 2021, it was further extended to six Northeastern states. In recent years, more rounded initiatives have been undertaken by the government. Also, the Hum Do initiative aims to provide eligible couples with information and guidance on family planning methods and services available. Other initiatives include a 360-degree media campaign to generate contraceptive demand and a scheme for home delivery of contraceptives by ASHA workers at the doorstep of beneficiaries.

For decades, India has relied on female sterilisation as its primary mode of contraception despite vasectomies being not only safer but non-invasive too. Nearly 75 per cent of all female sterilisation occurs in public institutions, and roughly one-third of them are done postpartum. As per National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5, 37.9 per cent of women use sterilisation to prevent unwanted pregnancies, much higher than non-surgical methods like pills (5.1 per cent), injectables (0.6 per cent), condoms (9.5 per cent), IUDs (2.1 per cent) or even male sterilisation (0.3 per cent). India shows heterogeneous geographical variation in the choice of contraceptive methods. While condoms are the most commonly used technique in the northern and western regions, the Northeast and eastern areas have a higher prevalence of pills.

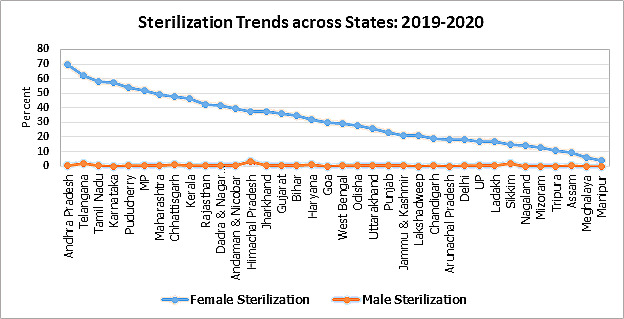

Source: NFHS-5

The above graph puts into perspective the striking gap between female and male sterilisation across states in 2021. Southern states/UTs like Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Puducherry and Karnataka lead in female sterilisation with more than 50 per cent coverage. But this is barely matched by the abysmally poor involvement of male counterparts.

Lack of Awareness

The focus on male sterilisation seems to have zoomed out of the Family Planning Programme post the scandal during the 1975 Emergency period when close to 6.2 million forced sterilisations were conducted within a year. In 1996, the Indian government did away with the ‘target approach’ to family planning and stopped setting targets or quotas for health officials for contraceptive methods and violating reproductive rights. Stigma, misinformation concerning side effects/complications and cultural and religious beliefs remain significant deterrents to the adoption of sterilisation among men. Between 2008 and 2019, only 3 per cent of all 51.6 million sterilisations done were vasectomies.

There is still a dire lack of awareness regarding alternative and reversible methods and knowledge of the side effects of surgical techniques for women. High unmet needs for modern contraception have been observed among poor and marginalised women, leading to poor reproductive outcomes and unwanted pregnancies. Poor cognisance of the current contraception methods’ side effects was noted among women in NFHS-5. Andhra Pradesh and Telangana rank lowest in terms of awareness of side-effects of the current methods of contraception, despite having the highest female sterilisation coverage in the country.

Popular in rural areas, postpartum or post-abortion insertion of Copper-Ts (or Copper Intrauterine Devices) is the only long-term reversible contraception method available in the country. Yet uterine bleeding and abdominal pain have been pervasive side effects. In states like Bihar, with highest Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 3 children per woman in the country, the increased prevalence of unwanted pregnancies is attributed to an absolute absence of counselling among women on birth-spacing and alternative methods. Fear of side effects continues to be a major deterrent in opting for alternate methods of contraception, even after almost 70 years of the family planning programme running in India. Other reasons are lack of knowledge, cultural beliefs, lack of decision-making power within intimate relationships and undesirable attitudes of service providers.

Lack of Consent, Unmet Needs

Besides lack of awareness about alternative contraception methods, consent too remains a grey area. Past instances of violation or non-agreement of consent have been reported on several occasions, especially among uneducated, disabled, tribal/minority women. Several women have been either coerced into, misinformed about the surgery or even never told about the possible risks that it may entail. Additionally, a procedure like mini-laparotomy or laparoscopic tubectomy may easily be done without women fully knowing.

Evidence indicates overemphasis on female sterilisation in family welfare programmes may lead to discouragement of other methods. Hence, in the absence of an expansive pool of choices in remote and rural areas or enough surgeons/physicians, poor quality of care becomes an acceptable standard. Chhattisgarh, for instance, has been historically notorious for time-bound and targeted mass sterilisation in camps with cases of botched surgeries and inferior standard of care. Incidents in Surguja (2021) and Bilaspur (2014) are some infamous examples of blatant disregard for government regulations and prescribed standards.

The skewed burden of permanent family planning is indicative of larger trends of early marriage and childbearing and health concerns arising out of unmet adolescent needs. A significant gap in truly understanding contraceptive requirements of the country arises from the exclusion of unmarried women and adolescent girls who are not commonly included in research studies. Hence, a big chunk of the population has rising and unrecorded unmet needs for birth planning. Surveys in Bihar reveal that more unmarried and sexually active women used contraceptives than married women in the 15-49 year age group.

Evidence shows smaller family sizes can reduce the infant mortality rate and improve maternal health. Enhancing access to and use of family planning methods, improvements in health infrastructure and women’s education and status can bring significant gains in infant survival. With the push for a two-child policy in states like UP, Assam and Gujarat, sterilisation is further incentivised and propagated. But this thrust seems unnecessary as most states have nearly reached replacement level fertility rate. Four out of the seven initial target states for Mission Parivar Vikas have already reached the goal of a fertility rate of 2 and below.

To achieve sustainable development goals, it is imperative for the government to ensure improved access to and strengthening of family planning services. The family planning programme should ensure that it is voluntary, informed and does not violate the dignity of women, to truly empower them to make choices for themselves and involve men in the process.

Mona is Junior Fellow and Shoba Suri is Senior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment