views

‘RRR’ song ‘Naatu Naatu’ has caught the fancy of the Western audience, capturing the white audience’s imagination like no other. Coupled with the Golden Globe win for Best Song (Motion Picture), the song has become an immediate sensation, with global audiences leaving their seats and dancing along to it in cinema theatres. While its unbridled, very Indian-flavoured energy might be novel for the Western audience, such “massy” songs in films are not a rare experience for Desi viewers.

So what set ‘Naatu Naatu’ apart from these songs which have inspired Instagram Reels globally? Structurally, it closely resembles other viral songs like ‘Saami Saami’ with a prominent and catchy hook step, a catchphrase that repeats like a leitmotif through the song, and a quirky tempo.

Evidently, ‘Naatu Naatu’ is set apart in the eyes of the Western viewer thanks to its context- India under colonial rule. The impact of colonialism is never over, the phenomenon having permanently altered societal structures. Still, it’s undeniable that there is a particular sensibility- an aesthetic, if you will- that relieves the ‘White Man’s Burden’. While it originated as the term for imperialists’ instinct to “civilise”, it has now shaped itself into a kind of performative guilt that allows relief while simultaneously absolving the performer of any further accountability.

This is the kind of art coming out of India that the Western audience is most likely to gravitate towards. After all, it is much easier to understand the impact of colonialism rendered in broad, blunt brushstrokes- a cruel, ill-tempered white man; a group of nice and benevolent white ladies who support the Indian protagonists, and of course, the protagonists themselves. This simplistic narrative appeals to the sensibilities of Western viewers who can gesture towards themselves as enlightened individuals, having participated in and celebrated the kind of music that condemns their racist past, obfuscating the fact that racism is not in the past at all.

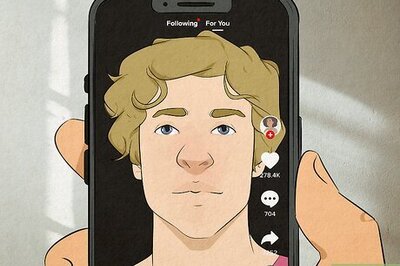

British colonial rule resulted in permanent political and socio-economic faultlines in India. The celebration of the freedom struggle- though it is undoubtedly deserving of celebration- at the current juncture is a tricky subject. It allows for our current realities to be swept under the rug when we can assume that the war against the impacts of colonialism has already been won. On social media, for instance, Indians have been rejoicing over the fact that Western audiences are now literally dancing to the tunes of India, without pausing to question why that serves as the absolute form of validation for this country’s artforms. Indians’ ultranationalist chest-thumping that follows any international accolade conveniently paints a glorious portrait of the country far removed from reality.

At the end of the day, Westerners are not interested in, say, a ‘Chaiyya Chaiyya’, which, when considered in isolation from the film ‘Dil Se’, is largely a love song that has by and by been imbued with political colours (think ‘Woh yaar hai jo khushboo ki tarah, woh jiski zubaan Urdu ki tarah‘). The Western audience would not want to concern themselves with the current nuances of India when an easily digestible packet of history already exists- India’s freedom struggle- far enough in the past that it now makes for relatively comfortable viewing.

Before ‘Naatu Naatu’, a similar phenomenon was observed with ‘Slumdog Millionaire’ song ‘Jai Ho’, which won the Oscar for Best Original Song in 2009. There is a certain kind of Indian and a certain kind of India that evidently appeals to the Western gaze: the one that performs against its poverty and oppressions, the one that either trumps or gets trampled by those structures. The Western taste for watching this constant performance and continual striving is criticised not just in cinema but in other artforms such as literature as well. This creates a need for marginalised people and countries to perform their historical and generational trauma in flagellating motions for the benefit of the Western viewer, to generate the pious fire of guilt with which they might purify themselves.

Art is intensely political, an instrument against fascism when it needs to be, but increasingly, there is an imperative for artists from countries such as India to become perfect packages of cultural representation. There are boxes to be checked, words and symbols to be displayed and aesthetic requirements to be met for an Indian song to be considered an ‘India song’. As it happens with every group that has been oppressed, they must constantly prove their goodness, abilities, and afflictions. It is not enough to just exist.

Read all the Latest Buzz News here

Comments

0 comment