views

Formatting Your Treatment

Aim for two-five pages. Adjust the length based on your audience and the script. Aiming for two pages keeps things simple and focused, while five pages is a maximum to stay under. Keeping it short makes it more likely that someone will read the whole treatment. Some people write treatments that are 30-40 pages long, but the chances of it being read increases if you keep it under five pages. A possible page breakdown is one page for basic information like the title, logline, characters and plot summary, one page or less for each of three acts, and an extra page to spare. EXPERT TIP Melessa Sargent Melessa Sargent Professional Writer Melessa Sargent is the President of Scriptwriters Network, a non-profit organization that brings in entertainment professionals to teach the art and business of script writing for TV, features and new media. The Network serves its members by providing educational programming, developing access and opportunity through alliances with industry professionals, and furthering the cause and quality of writing in the entertainment industry. Under Melessa's leadership, SWN has won numbers awards including the Los Angeles Award from 2014 through 2021, and the Innovation & Excellence award in 2020. Melessa Sargent Melessa Sargent Professional Writer Before you start your script, make sure you know what you want to write about. Melessa Sargent, the President & CEO of Scriptwriters Network, says: "Once you have a firm story idea and a main character, write out all the details of exactly what you want the story to be about. It should be in paragraph form, and it should only be a few pages long. Then, when you write your script, you can just follow that treatment."

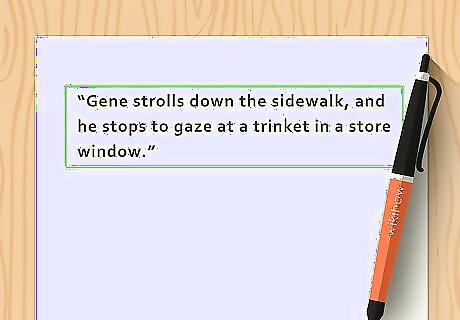

Write sentences that are one line or less. As you describe your script, use details and good description, but keep it brief. Read the sentences aloud to see if they are easy to read. If you have to take a breath partway through the sentences, it’s too long. Aim for sentences that are 15-18 words long, or less. This is a guide, because at times it may be necessary to write longer sentences. For example, “Gene strolls down the sidewalk, and he stops to gaze at a trinket in a store window.” This sentence shows action but is short and streamlined.

Keep the paragraphs short and direct. Trim your paragraphs down to three to five sentences. Always avoid writing large blocks of text because your reader will lose interest. Vary the number of sentences depending on what part of the plot you are describing. If your sentences are only eight words long, put more like 8-10 sentences in the paragraph. You don’t really want a paragraph that’s barely two lines long.

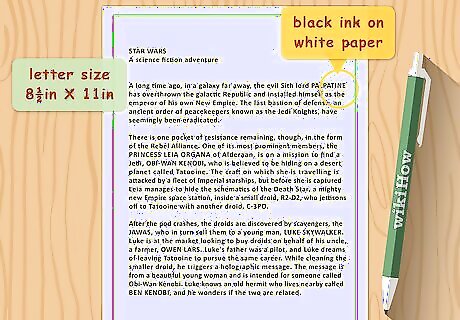

Print the treatment in black ink on white paper. Do not try to make your script treatment fancy-looking or more appealing to the eye. Using white paper and black ink is functional because it is the easiest to read. Your treatment is not the place for festive color schemes. Stick with basic 8½in X 11in (216mm x 279mm) letter size paper. Do not use cardstock, legal size, or other varieties of paper.

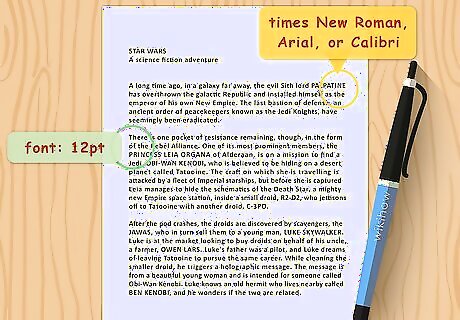

Make the text 12pt Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri font. It’s important that your script is physically easy to read, and these are the most basic fonts. You may feel like your content would look more appealing in something stylistic, but you’ll only make it harder to read. If you feel strongly about using a certain font, just make sure it is simple-looking.

Proofread the treatment carefully. It is absolutely vital that you check the treatment a few times before you give it to someone important. Have a friend or two read it over carefully to catch what you miss. It may even be worth having a professional proofreader take a look at it. The content is not the only thing that matters. A reader will catch your errors and it will turn them off to your script even if the story is great.

Including Relevant Information

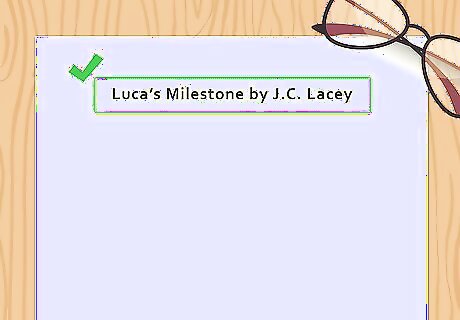

Put the working title and your name at the top of the treatment. Make the script title and your name easily visible and obvious. This information is how the filmmakers will refer to the treatment, so it’s important. Put it in the top center of the first page of the treatment. For example, write “Luca’s Milestone by J.C. Lacey.” Titles for feature-length movies should be italicized or left in regular font. Do not put them in quotes.

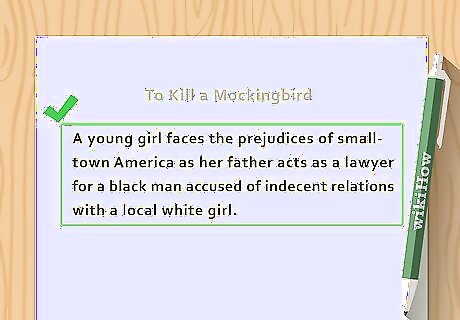

Create an interesting and developed logline. Write a one to two sentence summary of your script. Include a description of the main character, the goal they are pursuing, and the main conflict they face. This is the reader’s first insight into your script, so make it count. Think of this as the simplest way you could possibly describe the full story of your script. For example, for the well-known story To Kill a Mockingbird, you might write this logline: “A young girl faces the prejudices of small-town America as her father acts as a lawyer for a black man accused of indecent relations with a local white girl.”

Introduce the main characters. Start with your protagonist, or main character. Describe their appearance, as well as their main character traits. Discuss the characters they interact with most throughout the main arc of the story. Be sure to include the primary antagonist, if there is one. You don’t need to include a full list of every person who appears in the story, but describe the ones that are important to the main story. You have freedom with your character descriptions, but aim for two to three sentences that are full of detail for each character.

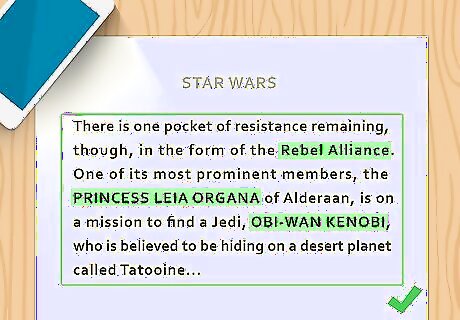

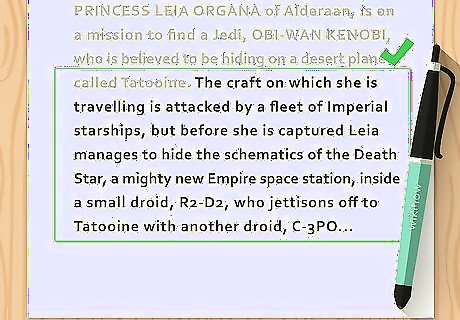

Expand on the logline in five to ten paragraphs. Describe your script in the way that makes the most sense to you. Tell the story chronologically from beginning, to middle, to end, or describe the key plot points first and the smaller parts second. Don’t include subplots in your treatment. In a three act format, act one establishes the characters and basic setup, act two brings in a major conflict, act three intensifies and then resolves the conflict. Be sure to include the climax and the resolution. You may want to save the big finish for the screen, but this is not the place to hide it. Give the treatment reader the ending.

Creating the Tone of the Treatment

Write for your audience. You may write the treatment for a producer, director, or even an actor. Because of this, write it for that person. Adjust the content and the way you present it based on who it is for. Also adjust based on if you know the reader personally or not. For a director, you might focus more on the way each scene looks and what set pieces are involved. If you’re writing for an actor you’d like to play a role, give more attention to their role than to the other characters.

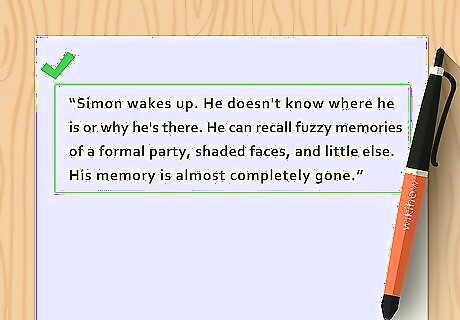

Make the treatment connect emotionally. No matter what genre you’re writing the treatment for, it has to hit the reader with some real emotion. Make them feel fear, sadness, or joy by the way you describe the characters and the story. This is the hook that forces the reader to connect with the story. Don’t present something that is different from your script. Use the emotion that is part of the story and bring it out in the treatment. Convey emotion by showing how characters react. Write, "He turned his face away," which shows he is ashamed or hiding something. Describe a character looking at a photo for just a few seconds before they start crying. Have a woman brush off a man's touch, a kid step back as their mother reaches toward them, or a man look in the mirror and shrug.

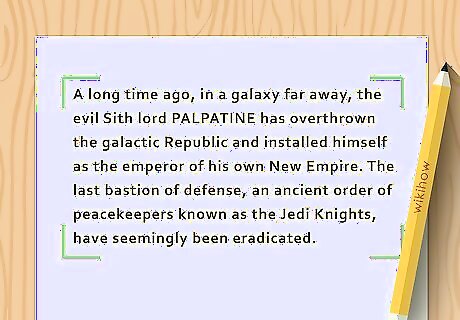

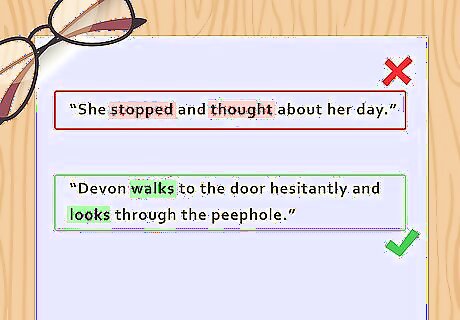

Write the story in present tense. Your treatment should read as the audience will see it. Describe everything as it happens, not as if it has happened already or will happen. This can be tricky, because it’s not always your first instinct. Check your writing over for tense shifts. For example, write, “Devon walks to the door hesitantly and looks through the peephole.” Don’t write, “She stopped and thought about her day,” because that shifts to past tense.

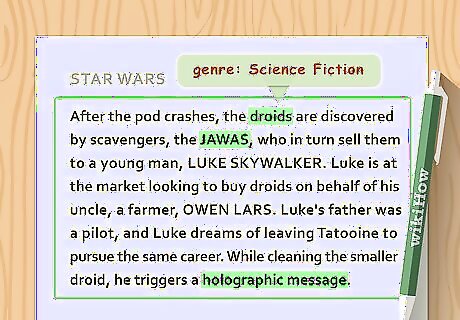

Reflect the script's genre in your treatment. Describe the movie in a similar way to how people will feel during it. If your goal is for the film audience to be scared, make the treatment instill fear. Make the reader laugh if you're pitching a comedy. Important aspects of the genre are important in the treatment, too. Keeping tropes of the genre in mind is important. Use them purposefully when you must, but don't rely on them.

Comments

0 comment