views

Prompting Your Memory

Retrace your steps. Research has found that a lot of memory is “context-dependent,” meaning people are better at remembering information in an environment that matches the environment in which that information was learned. For example, if you thought of something in the living room and forgot it by the time you got to the kitchen, try going back to the living room. It’s likely the return to a familiar context will help you retrieve the forgotten information.

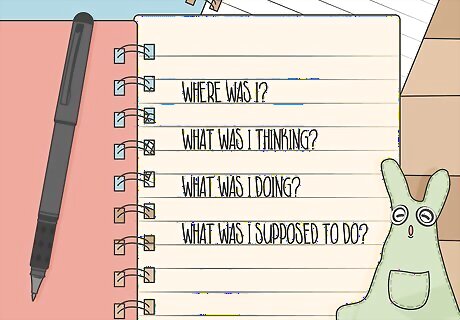

Reconstruct your train of thought. If you can’t physically go back to the place you were when you had the thought you’ve now forgotten, try imagining where you were, what you were doing, and how your thoughts connected to each other. Because many memories are stored along overlapping neuronal patterns, reconstructing your train of thought may help retrieve the forgotten thought by stimulating related ideas.

Recreate the original environmental cues. For example, if you were listening to a particular song or browsing a particular webpage when you had the thought you’ve forgotten, bringing up that information again will likely help you retrieve the information you forgot.

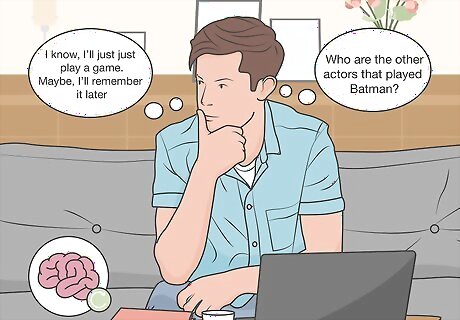

Think and/or talk about something else that's not related. Because your brain stores so much information along overlapping neuronal patterns, it can be easy to get stuck retrieving related but “wrong” information, such as all of the other actors who played Batman, but not the one you’re thinking of. Thinking about something else can help “reset” your retrieval.

Relax. Anxiety can make it difficult to remember even simple information. If you are having a hard time remembering something, don’t get worked up over it; try taking a few deep breaths to calm yourself and then try to think of the information.

Enhancing Your Memory

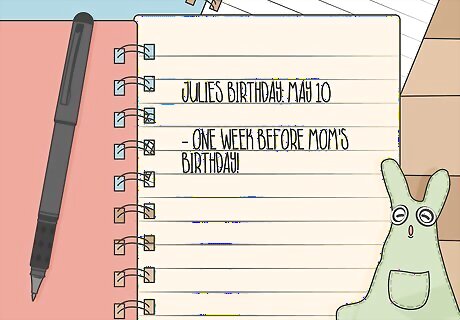

Create “distinctive cues” when you want to remember something. You’re more likely to encode information it into long-term memory if it is associated with distinctive information that can serve as a “cue,” or starting place. Anything can serve as a cue, but actively relating new information to things you already remember is a good strategy. For example, if you have a conversation with a friend at the coffee shop and she tells you about her upcoming birthday, try connecting the memory of the conversation to something you already remember well: “Melissa told me her birthday was on June 7. That’s just a week after my mom’s birthday.” These cues can also be sensory information. For example, smells can trigger vivid memories in many people, like the smell of baking cookies reminding you of days spent at your grandmother’s house. If the memory is possibly connected to a smell -- in this example, maybe the smell of coffee or cinnamon rolls from the coffee shop -- try stimulating your memory with a whiff of the familiar odor.

Connect memories to a specific place. Memory is strongly tied to the environmental contexts in which the information is originally learned. You can purposefully use this connection to help you encode information for retrieval later. For example, verbally connect the information you want to remember to the place: “When we met at that new coffee shop on Main Street, Melissa told me her birthday was on June 7.”

Repeat the information immediately. If, like many people, you forget names almost as soon as you’ve been introduced to someone new, try verbally repeating that information as soon as you get it. Connecting it to as many cues as possible -- what they look like, what they were wearing, where you are -- will also help you remember it later. For example, if you’re at a party and a friend introduces you to someone named Masako, look directly at them as you smile, shake their hand, and say, “It’s nice to meet you, Masako. That shirt is such a pretty shade of blue!” Reinforcing all of this sensory information at once may help you encode the memory for later.

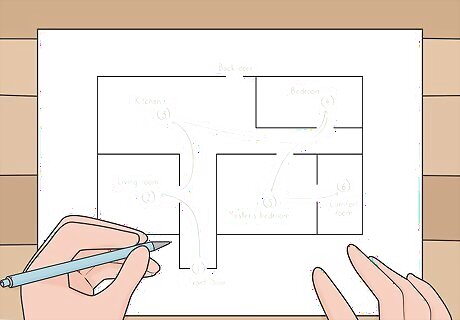

Create a “memory palace.” Memory palaces are a common mnemonic technique used to create connections between information and environmental contexts -- in this case, though, those contexts are all in your imagination. Even the famed (if fictional) detective Sherlock Holmes uses this technique! This technique takes some practice to perfect, but it can be very helpful for storing information that you want to remember because it emphasizes forming creative, even absurd connections between places and memories.

Avoid learning in high-stress situations. This isn’t always an option, but if you can avoid learning new information under high-stress conditions -- for example, the wee hours of the morning before a huge exam -- your ability to recall those memories later will likely be improved.

Get plenty of rest. Sleep -- especially REM (“rapid-eye-movement”) sleep -- is crucial in processing, consolidating, and storing information. Sleep deprivation affects the firing of your neurons, making it harder to encode and retrieve information.

Drink water. Do something different, believe you are helping yourself and you will remember it. If your phone has a voice recording function, you can use that to send yourself voice notes or voice text messages. You can also download and use free recording apps on your phone. If you have a lot to remember, pick out a maximum of 3 keywords and memorize them. If you can, take a screenshot or picture of what you need to remember and send it to yourself. It is great for phone numbers or contact information you don't have stored in your phone already.

Comments

0 comment